Writer: Martin Pasko

Artists: Walt Simonson, Keith Giffen

Colourist: Tatjana Wood

DC Comics, 1985 (collection)

We are cheating on the arithmetic of our revisitation to the collected stories within The Immortal Dr Fate. Forty years since 1985 was last year (2025). But The Immortal Dr Fate was a series which reprinted innovative stories by Martin Pasko and Steve Gerber from Doctor Fate backup stories appearing in The Flash #306 (February 1982) to #313 (September 1982) as well as 1st Issue Special #9 from 1975. So, perhaps, we are actually four years too late.

Dr Fate is a character which was created in 1940 during the height of the American superhero comic book boom, and who prominently featured in the 2022 motion picture Black Adam. Fate is a “Lord of Order”, a being who seeks to stop malign magical forces, including counterpart “Lords of Chaos”. Fate’s powers are granted to him by Nabu, a “godling” out of Egyptian mythology. The fundamental premise is a very basic moral dualism.

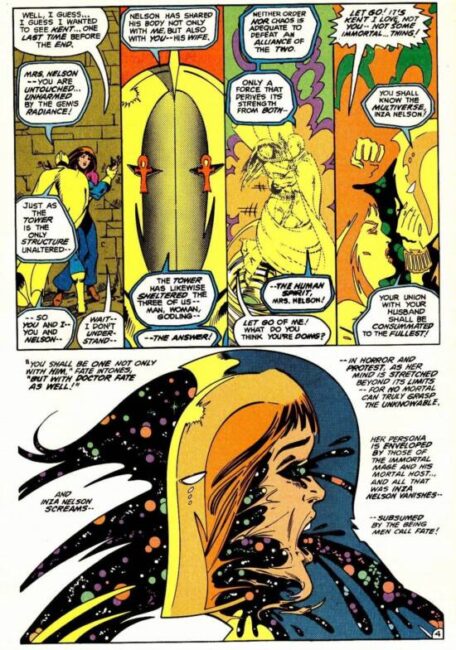

As the character evolved over the decades, however, writers began to draw a distinction between Nabu and Dr Fate’s alter ego, Kent Nelson. Nelson is no longer simply a magician, but instead is a man who is possessed by Nabu by way of the character’s iconic, slightly eerie golden helmet. This series of stories collected within The Immortal Dr Fate firmly consolidates this idea. At one stage, Dr Fate speaks to Kent Nelson’s wife Inza as “Mrs Nelson”, underscoring the difference between host and spirit. (As an aside, Roy Thomas, the writer and editor of the 1980s series All-Star Squadron, used the split between Nabu and Nelson to explain why, in 1941, Dr Fate was suddenly depicted in comics with a truncated helmet and different, much-less-sorcerous superpowers – the Helmet of Nabu was stolen and cast through multiple magical dimensions together with its three-eyed, green-hued thief, apparently forever.) There is a superhero, but it is not a traditional superhero comic. Kent and Inza’s relationship, overlaid by Nabu’s cold presence, is a Gothic horror romance characterised by ghostly possession.

It was a curious time for DC Comics to move into the horror space. The purple patch of DC Comics’ horror titles concluded as this story was being originally published (House of Mystery ended in 1983 after 24 years; Ghosts ended in 1982 after eleven years; Weird War Tales ended in 1982 after 11 years). But these Dr Fate stories involved a minor character as a back-page filler to one of DC Comics’ second tier character’s monthly titles, and so, perhaps, even after the infamous DC Implosion in 1978, there was not much of a financial risk.

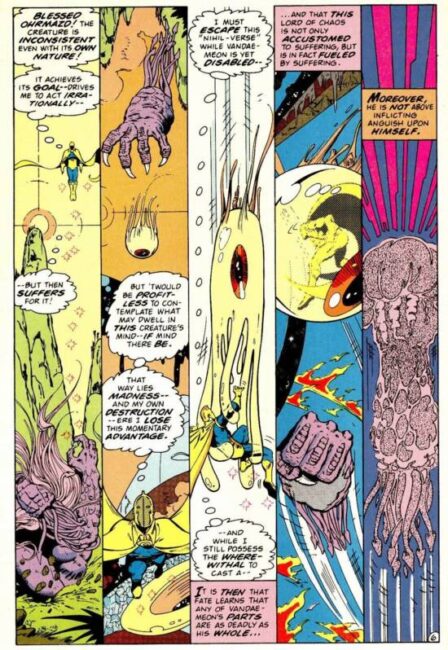

The story itself has the titular character fight, first, a revived mummy named Khalis seeking Dr Fate’s Amulet of Anubis; second, a malevolent Aztec god accidentally released from an ancient artefact; and third, a rogue Lord of Order acting in conjunction with a nightmarish Lord of Chaos called Vandaemon. (The satisfying twist in the Khalis storyline is that he died in service to the Egyptian god of death, Anubis, but upon being called back to life finds to his disbelief that Anubis has forgotten him and regards him with contempt. Gods are fickle.) These plots are exciting, fun, and each adversary seems to pose a genuine threat to a character often depicted as a nigh-unbeatable superhero.

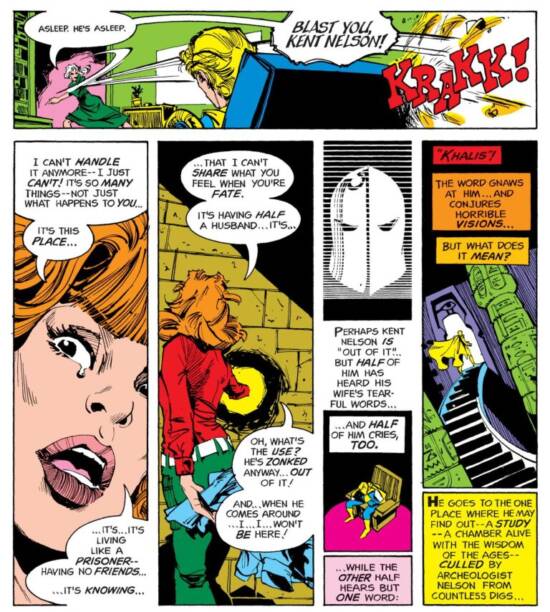

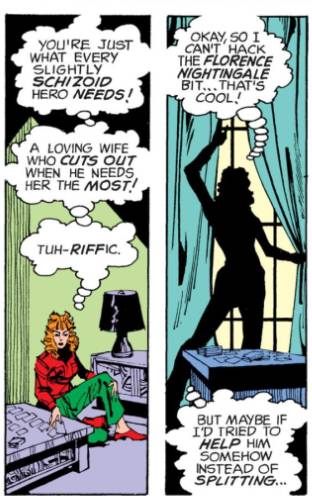

In some respects, however, it has not dated well. The dialogue is stilted and misogynistic. Nelson treats his wife Inza with frustrated contempt, and Inza is depicted as an unfaithful drip. Writer Martin Pasko has explained what he was out to achieve – from 1st Issue Special #9 (December, 1975) | Attack of the 50 Year Old Comic Books:

[Editor] Gerry [Conway] wanted to include the Inza character… and that meant — especially with most comics readers in the mid-’70s embracing feminism and gender equality — figuring out how to do more with her than playing the same old damsel-in-distress card…

So I said to myself, let’s make her more independent-minded, a woman who pushes back against the oppressiveness of her life. But what, exactly, was that oppression? Well, she was married to a super-hero but wasn’t allowed to share in his experience unless she was somehow victimized by it. And she was forced to live, we were told by the source material, in this “tower without windows or doors” that looked more like a medieval prison than a magic castle. So she was, in essence, held hostage by her husband’s circumstance. But [at the same time] I wanted Inza’s rage and frustration to be tempered by love for Kent and by sympathy for his oppression.

I thought, “Let’s make Inza a super-hero ‘widow,’” likewise cut off from her husband during crisis situations and unable to help him… But what about that sympathy for her husband that tempers her resentment? What was his burden? That question led to my second pitch, which was that Kent Nelson was not the super-hero; something that inhabited him was.

What the abstraction called ‘Dr. Fate’ really came from Walt’s pitch about Lords of Order, which was in response to my idea that Nelson should be just the guy whose body was used by an incorporeal entity that lived inside the helmet (thus providing a rationale for why a helmet at all). Nelson would be presumably only one of many people in history to serve as the “host vessel,” though we never explicitly stated so. This meant that Kent wasn’t being insensitive to his wife’s plight; he was simply powerless to ignore the call to service from the thing in the helmet.

In so far as the romance goes, it does not work. Inza sounds emotionally fragile and very far from a feminist figure:

And later:

It is instead the art which is a delight. Let’s begin with Walt Simonson’s work on the Khalis storyline, which is marvellous.

In an interview for Comic Book Artist #10 (October 2000), again, quoted in 1st Issue Special #9 (December, 1975) | Attack of the 50 Year Old Comic Books , Mr Simonson notes the artistic inspiration of Steve Ditko on that other magical doctor, Dr Strange, owned by Marvel Comics:

So, when I was doing Doctor Fate, I was trying to develop an alternative way to visualize structured magic. It grew out of my admiration for what Steve [Ditko] had done, of course, and owed a lot to it, but I was searching for a different visual basis. In the end, I came up with the idea of using the ankh as a symbol for Doctor Fate, the Egyptian symbol for life, which seemed appropriate for the character. And I used typography as my structure the way I’d learned at RISD, where we’d extract a letter from a specific typeface, and then play with it, make it a design element. We’d use it as a building block and make circles and spirals, geometric shapes, anything the form suggested. It was really a kind of play and exploration. And you discover negative space and positive space in ways you haven’t seen before and can build on. It must have worked out okay because everybody who’s drawn Fate since has used the ankh.

In Immortal Dr Fate #3, Keith Giffen takes over as penciller, but it is the legendary colourist Tatjana Wood who steals the show. Wikipedia contains a footnote to Ms Wood’s entry – see Tatjana Wood – Wikipedia – quoting Paul Levitz: “Virtually all DC covers from 1973 through the end of the Bronze Age were colored by Tatjana Wood.” Ms Wood provided a colour house style which was recognisable in all of DC Comics’ covers of this error – eye-catching hues and tones which fleshed out the work of pencillers and inkers. This title is a tour de force of her skills as a comic book colourist:

The wild colour palette is psychedelic and completely appropriate for a storyline which takes place in realms beyond mortal understanding, involving luminous magical spells with lurid consequences:

Occasionally, it seems to us, that Mr Giffen is happy to take a back seat and enables Ms Wood to demonstrate her craft, giving life to Mr Pasko’s grand, narration-heavy panels. This series was in many ways, it seems to us, a better example of Ms Wood’s skillset than her acclaimed work on the title Camelot 3000, published from 1982 to 1985.

In terms of visual dynamism, The Immortal Dr Fate is hard to beat even forty (or so) years later. Your reviewer was delighted to re-read it. The infusion of horror themes with traditional superheroics, and wonderfully vibrant, trippy art, remains compelling.