Writer: Grant Morrison

Artist: Frazer Irving

Legendary Comics, 2015

It is an object of scientific and existential fascination. Sitting deep within the Milky Way Galaxy, Sagittarius A* is the location of a supermassive black hole, a thing so powerful that it alters the course of stars. Wikipedia notes that, “The name Sgr A* was coined by [astronomer Robert] Brown in a 1982 paper because the radio source was “exciting”, and excited states of atoms are denoted with asterisks.” Just before the hardcover version of this title, Annihilator, was published as a collected work, on 5 January 2015, NASA reported observing an X-ray flare 400 times brighter than usual emanating from Sagittarius A*. Urbane theories include asteroid debris or magnetic field entanglement. Or, perhaps, Max Nomax was up to something again.

Scottish writer Grant Morrison is perhaps best-known for his trippy interpretations of superheroes, with various takes on American DC Comics’s portfolio of characters including Animal-Man, Doom Patrol, Justice League of America, Superman, Batman, and most recently Green Lantern. For Marvel Comics, Mr Morrison wrote New X-Men. Mr Morrison also worked with artist Frazer Irving on the limited series Seven Soldiers of Victory and Batman and Robin. In 2014, Mr Morrison and Mr Irving came together again to produce Annihilator. This title is of a different genre, for while there are caped cosmic warriors, it is better characterised as glamrock science fiction, complete with its own rockstar – Max Nomax.

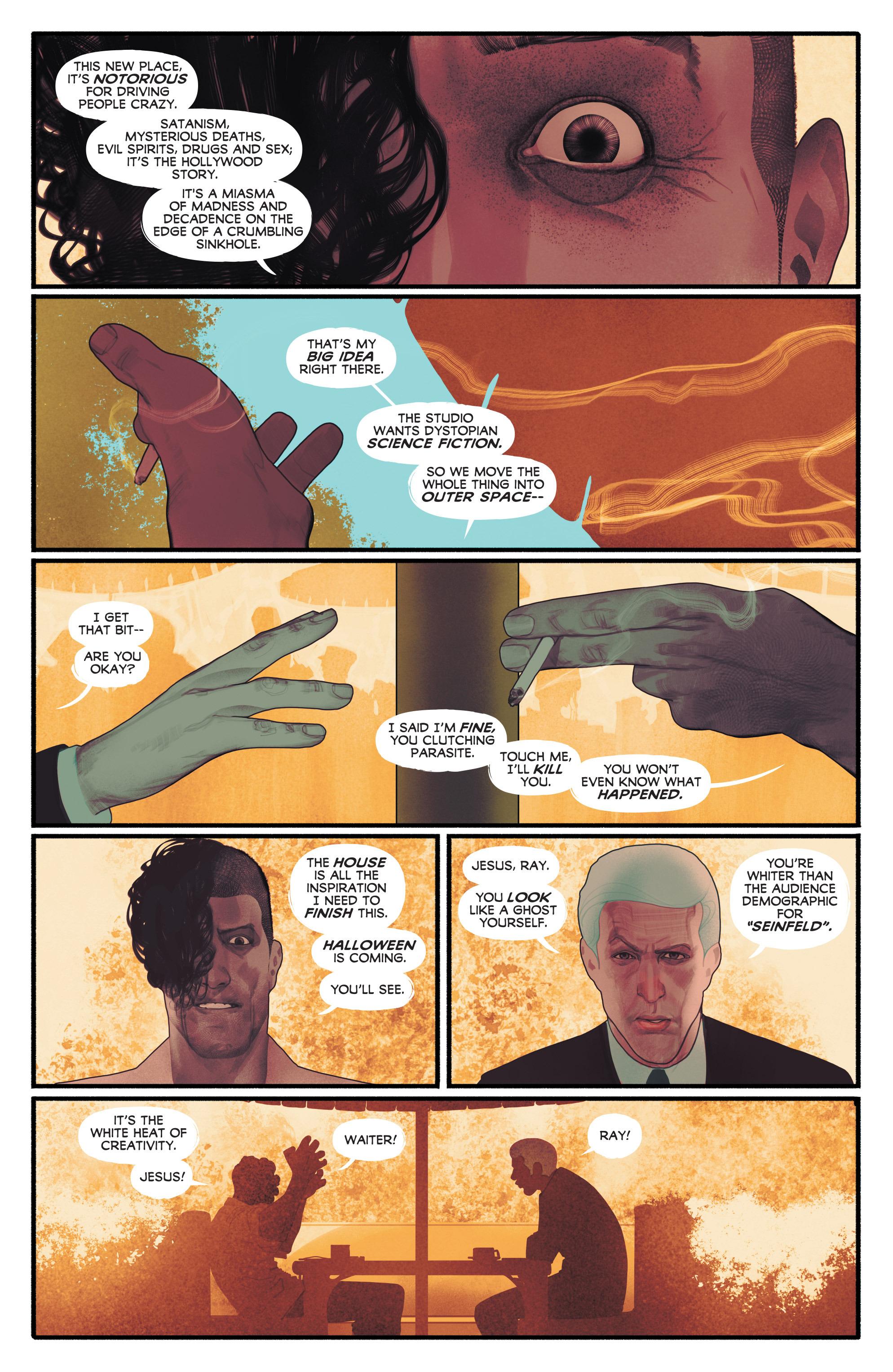

Hollywood screenwriter Max Spass (pronounced “Space”) discovers he has a brain tumour. Spass has sold a partially-completed script to a movie studio about a “haunted house in space” and is under pressure to complete it. The brain tumour naturally causes Spass to rethink his priorities. In a 2014 interview for Comicbook.com https://comicbook.com/news/exclusive-grant-morrison-talks-annihilator/ , Mr Morrison suggests the story came out of his jaundiced time as a script writer in Hollywood:

“Here’s what Hollywood is, the kind of people I’ve met. Here are the men I’ve met, the kind of women I’ve met, here’s my take on this strange world where people are creating fictions which sell to the entire globe. This one was very much about my Hollywood experience and I think you can probably see that in it.”

Spass is shallow, manic, conceited, vain about his creative prowess, and self-pitying. Spass emotionally abused and then stalked his ex-girlfriend Luna, has cocaine-fuelled orgies with prostitutes, and tries to kill himself upon receiving his diagnosis. Spass is funny, true, but he is a thoroughly unlikeable character. It does not seem as though Mr Morrison has a particularly sunny view of Hollywood culture. Mr Morrison stated in an interview for Collider https://collider.com/grant-morrison-annihilator-interview/ that, “the notes that Spass receives on his screenplay are word for word notes which I’ve received on previous works that I’ve done, so it certainly helped having those and essentially, this is my revenge for receiving them.”

The character of Spass’ current screenplay, Nomax, turns out to be real. Nomax, an arch-villain from space, is the story’s antagonist. Also self-absorbed and manic, Nomax is ridiculously over-the-top, whereas Spass’ eccentricities are somewhat too believable. Nomax is also dramatically confident in his own abilities.

Aside from that delineation, there is not much daylight between the two in respect of characterisation. At first, this seems like a bold decision on characterisation by Mr Morrison. Characters that are too similar tend to blur a plot. It is why American superhero comic book readers will never see a publisher crossover between the twin ultra-capable Batman and Black Panther, why the Joker’s psychotic interactions with the evil The Batman Who Laughs are awkward, and why Image Comics’ efforts back in the 1990s at Tomb Raider / Witchblade stories were like listening to a needle stuck on a vinyl record. Here, Nomax and Spass even look a little the same.

The initial impression is that Mr Morrison pulls the trick off, however, by grounding Spass with spite and the dreadful relationship with Luna, and pushing Nomax into the stratosphere with vainglorious soliloquies and unreasonable demands. Nomax is evil but genuine: Spass is unlikeable and weak. But the arrangement is much more complex than this, and is a misdirection by Mr Morrison. More on this later.

In any event, Nomax says he has done a terrible thing. The tumour in Spass’ head is not a tumour. Instead, Nomax has shot Spass in the head with a memory dump, which if not released as the screenplay will kill Spass. The more Spass writes, the more the tumour shrinks. Nomax himself does not know what Spass has locked up in his brain, and demands that Spass finishes his screenplay so Nomax can know how it is that he escaped his fate and what to expect next.

But even this is misdirection. Nomax has not really placed a data dump in Spass’s brain. It is a lie, an incentive to have Spass cooperate, because Spass, through the cosmic workings of Sagittarius A*, has Nomax’s recent history locked up in his subconscious.

Nomax was imprisoned by Vada, a God-like ruler of the galaxy, for unspeakable crimes. Nomax’s prison was a space station called Dis, orbiting Sagittarius A*. (Readers of Dante Alighieri’s The Divine Comedy will recall that Dis was a city in hell, and is Greek for “not of”.) Staring into the abyss has done terrible things to the previous inhabitants of the space station, including the creation of a horror called the Oorga. The Oorga does terrible things to Nomax, but Nomax defeats it with a choice of being chained to a metaphoric wheel in hell like the Greek character Ixion, or destruction by Sagittarius A*.

Nomax, like Captain Ahab in Herman Melville’s Moby Dick, shakes his fist at God. But unlike the impassive and disinterested God of Ahab’s psychosis, Nomax’s god is paying keen attention, and dispatches an archangel, Jet Makro, to finish Nomax off.

Jet Makro (and the other annihilators who serve Vada) are bright and terrifying angels, as drawn by Mr Irving. But it is Mr Irving’s rendition of Spass particularly is tremendous. Mr Irving has in our view never set a foot wrong in his art. The pale Pilgrim descendants of Klaxon the Witchboy’s subterranean world in Seven Soldiers of Victory were plainly zealots from their rictus of their smiles, and that was communicated by Mr Irving’s art as much as by Mr Morrison’s dialogue. Here, Spass is bronzed by Californian sun, handsome enough to date and torment a hot Romanian model (Luna), sports the beard stubble of someone who has lost track of the hour of the day, and has a ridiculous trademark haircut. Mr Irving admirably provides an impression of Spass’ headspace from his appearance.

Nomax is the story’s Ahab, but there is a big wallop of Norse mythology’s trickster god Loki in there as well. Nomax cleverly talks Jet Makro into his own self-destruction, in a very Loki-esque way, but fails to create a perfect universe from which to run away from Vada. As American writer Robert Rodi noted in his excellent comic Loki for Marvel Comics, a lord of misrule is incapable of rule. Planning always fails. Chaos is inherent. But the cunning always survive.

Luna is the only decent character in the comic. She is the counterpoint to both Nomax and Spass – grounded, decent, emotionally fragile, coherent, and normal. Jet Makro recognises it, and Spass is compelled by it. Luna’s relationship with Spass was a trauma. Being dragged by Nomax back into Spass’ orbit, just as Spass’ brain starts imploding, is to say the least completely unwelcome.

By the end of the story, the jigsaw pieces start to come together:

- it has become apparent that Spass and Nomax are mirrors of each other, thanks presumably to the uncanniness of Sagittarius A*, as are Luna and Nomax’s object of desire, Olympia. The observation, above, about the difficulties of having two almost identical characters in a work of fiction become redundant when the concept underpinning the plot is revealed. The giveaways are a little subtle: Spass complaining that he tried to put something of himself into Nomax’s characterisation when writing his screenplay, and Luna complaining that she is represented in the screenplay by a beautiful automaton in a coma of grief.

- Spass hurt Luna but loves her: Nomax loves Olympia but hurts her by telling her he never loved her, as a way of getting at Vada (“the ace of assholes” as Spass puts it: Nomax is, when the truth comes out, actually worse than Spass).

- Nomax and Olympia jump into the lurking super massive black hole to escape Vada: Spass has his own black hole lurking within his head. Mr Irving towards the end captures the effect of the tumour upon Spass. Black holes lurk in Spass’ vision like a melted movie reel – appropriately Hollywood. (Nomax comically tries his hand at brain surgery by the end of the story and unexpectedly saves Spass by removing the mass of malign tissue.) Is the surname “Spass/ Space” a play on words because Nomax literally comes from “space”? Are the two black holes connected?

- Vada complains that Nomax has created a flawed and sinful universe (our own) and, convinced by Nomax and Luna not to destroy it, exiles Nomax to it. (Vada himself is at the end of the story pretty cagey about Nomax’s talent for mischief.)

- Which is the original image and which is the reflection? Is there a difference? Did Nomax create our universe, and with it Spass and Luna, or did Spass create Nomax’s universe and with it Nomax and Olympia? Perhaps both, given the mystery of Sagittarius A*. There is something quite metaphysical and unknowable about the driver to the plot, as strange and inexplicable as a burst of cosmic energy from the galactic core.

In the interview for Collider, Mr Morrison talks of a sequel. “The sequel is already in the works in fact! Again, the useful anti-hero archetype (as displayed by Spass and Nomax) can be used again and again in a lot of different stories. It’s just a matter of when really.” Sadly, we have yet to see it. Happy 5th birthday, Max Nomax.