Writer: Kev Sherry

Artist: Katia Vecchio

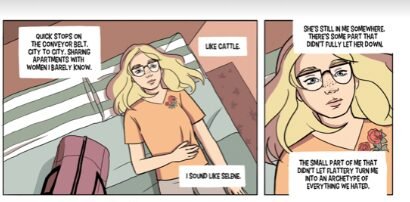

Sharply feminist and created with artisanal precision, Warpaint is a profound independent publication from writer Kev Sherry and artist Katia Vecchio. It follows the life of a girl called Selene, from the perspective of her high school friend Sophie Ember, years later, learning of Selene’s death and lapsing into the memories of her childhood with Selene.

Selene is a force of nature. Selene of course in Greek mythology is a dark moon goddess, and the character Selene in Warpaint does not let the traditions running with the name down. She cajoles her friends into borderline shamanic rituals, and is happiest in her fantasy of mystery and sorcery. The villain of the tale is a boy called Connor Forsey, who remorselessly bullies introverted class mates, protected by the shadow of his criminal brothers. When Forsey throws a brick at Selene, at the conclusion of the first issue, Selene’s face is covered in blood and she wails as if she had been brained. Forsey flees in terror. What Selene has done is to outflank Forsey: she has used her menstrual pad to smear her face in blood in order to give Forsey and his confederates a fright.

Selene was indeed the Greek goddess of the moon, but she was also known as Mene, which is one of the linguistic cognates of the words “menstruation”. Correlation between the human female menstrual cycle and the month-long rotation of the moon has been debunked, but the myth and symbolism associated between the two is strong and imagery invoking the moon (see for example the cover) is repeated throughout the comic.

Forsey extracts revenge the next day during school by squirting a bottle of blood up Selene’s legs. It evolves that Forsey killed and drained the blood from Selene’s beloved cat, Emily P, who has been dumped in a rubbish bin. Mr Frome, a teacher, sees what has happened but does nothing, fearful of Forsey’s criminal brothers. “It’s obvious you’re over emotional at having embarrassed yourself,” says Frome when confronted by Selene. “Over-emotional” is a term for women with Victorian connotations. Not much has changed, apparently: Salon Magazine recently reported https://www.salon.com/2019/04/16/are-women-too-emotional-for-public-office-even-after-trump-some-people-believe-that/ the results of a University study demonstrates that “13% of Americans still believe that men are “better suited emotionally for politics than most women.””As the story reveals, the consequences of a challenge to masculinity are fearsome. But so is Selene.

Selene is clever, but Selene is also wild and erratic. Selene misconceives the nature of her relationship with her mother, a revolutionary but a terrible caregiver. Running away to London to live with her mother was the path to freedom. And Selene’s heart breaks when her mother inevitably lets her down. Like the rest of the story, it is executed with precision, cogs spinning seamlessly.

The characterisation is otherwise well-executed. Sophie is a bystander, nervous and fretful, who only discovers the veneer of confidence as an adult. Even Forsey, nasty and vengeful, attracts sympathy as being an unhappy product of his environment, bullied by his brothers and with his nascent masculinity teased and taunted. You can, if you squint your eyes, see that Forsey would have been a good kid if he had better influences.

As to the art, Ms Vecchio has a magic trick. She flickers the cast between the ordinary world and a rosy spirit world, where Selene is a fierce goddess of the hunt and her companions are equally adorned in the indicia of pagan magic. Ms Vecchio uses her considerable skill to jar the reader from the world of imagination and freedom back to dirty bedrooms or derelict buildings filled with old brick rubble, and upset teens with their starburst emotions. It is hard to know what is imagination shared between the teens in Selene’s coterie, and what is Selene’s delusion. During the crescendo, the story crashes between a fight with a demon and Selene in her Ragnarok wielding a mystic hammer, contrasted with a brutal sexual assault in a forest. Selene is whisked away by policemen with devils’ wings. The artistic layout is, with respect, masterful.

Warpaint is misnamed. It is instead a warcry. This comic is a jagged shard of crystal suspended, rotating in the moonlight. In a sequence which hooks in the memory like a claw, the creative team castigates the cult of emaciation in the world of modelling with a series of panels in which a slender young model, nude, is humiliated for being overweight. Selene is dead, psychiatric drugs worming into her liver, caged in a ward. Sophie realises she is part of the problem.

A glance in a mirror and Sophie sees an imaginary version of Selene smiling back. Everyone goes through life with regrets, failings of character and self-reproach rusted over by the passage of time. The story asks, in a perfect closed loop, what will you do about it?

Warpaint is available on Comixology: https://www.comixology.com/Warpaint/comics-series/123381