Writer: Owen Hammer

Artist: Mariano Navarro

Colourist / Letterer: Herman Carrera

Hammer Comics, and Scout Comics, 2021

Owen Hammer contacted us some time ago regarding a review of this title, and we regret letting it languish. We did not expect that Mr Hammer’s quip-filled comic Von Bach was so thoroughly entertaining. Here is the promotional copy from Mr Hammer’s website: VON BACH

Doctor Heinrich Von Bach was the nineteenth-century scientist resurrected from the dead by his own ungodly invention. At least that’s the story Hollywood told when they got hold of the gothic romance novel written about the good doctor. For a hundred years they’ve made as many films based on the bloody life and undeath of Von Bach.

Today, a major studio is finishing a big budget “Von Bach” movie. But suddenly, the real Von Bach returns to life in Hollywood and he is going to teach the cast and crew the true meaning of “development hell.”

VON BACH! Greater than the power of life! Greater than the power of love! He possessed the greatest power of all! SUBPOENA POWER!

Playwright Owen Hammer has adapted the play for the comics medium and versatile artists Mariano Navarro and Hernán Cabrera will be bringing his vision to life.

“Von Bach” is a satire that pokes fun at pop culture and society in general. Nonetheless, there is a powerful story about the search for meaning and the struggle for one’s own dignity. And of course, some genuine scares!

First, because this review lingers over the plot and comedic aspects of the comic, a word on the art. Mariano Navarro’s work in this comic vaguely reminds us of Kilian Plunkett’s style of art but with less cross-hatching, lending it to be a series of caricatures, and almost cartoonish. With great respect to Mr Plunkett’s skills, Mr Navarro deploys a much wider variety of facial expressions, which was necessary in this title to convey the humour. Mr Navarro’s rendition particularly of principal character Minna Tseng imbues her with emotion and emotional shift: thoughtful, pensive, stressed, honest.

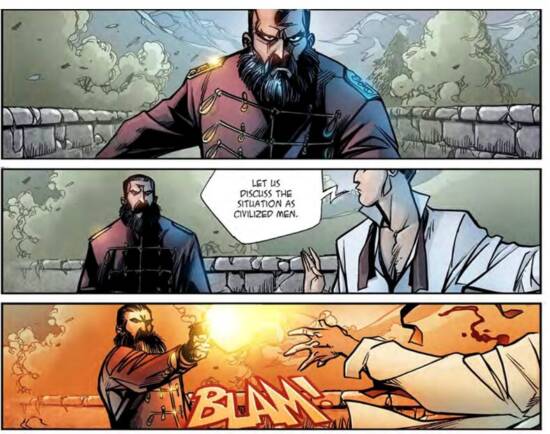

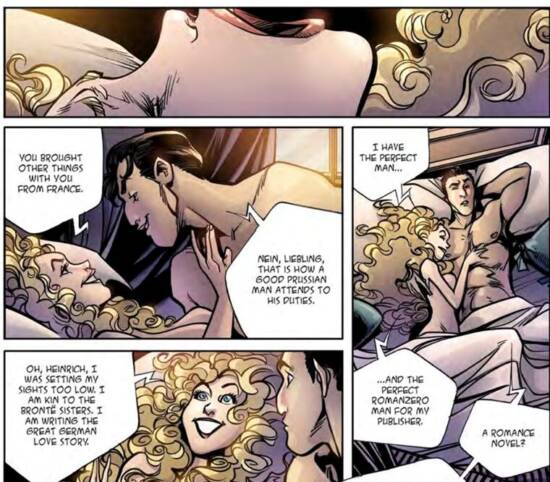

The story begins in Bavaria in 1888, where Elsa Jagger and her friend Bronwyn visit the remote castle of Dr Heinrich Von Bach, a handsome gentleman-scientist, and apparently a medic in the Battle of Sebastopol. (This battle was a late episode of the Crimean War, involving an Anglo-French alliance against Russia, some thirty years before – perhaps a little too early for this timeline.) As a consequence of a liaison with Elsa, Von Bach falls foul of her kind-of fiancée, Drossel Tannenberg. Von Bach attempts to parley with Tanneberg, but Tannenberg’s response is limited to a single gunshot.

Von Bach’s fellow scientist attempts to revive him with a prototype defibrillator, but his corpse is accidentally and anticlimactically incinerated. Or is it? The truth of Von Bach’s fate comes out slowly over the substantive story.

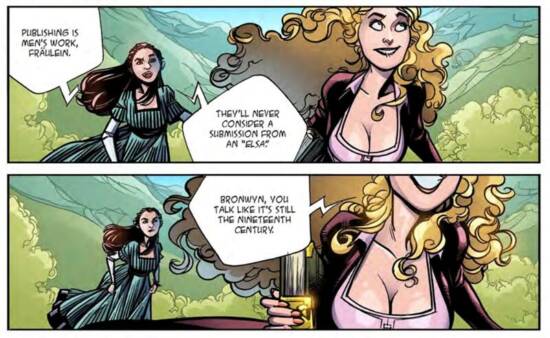

Elsa writes a book detailing what has happened, against Von Bach’s wishes. By 2013, when most of this story is set, Elsa Jagger’s novel is the subject of academic study and has been made into countless movies. Minna is a Von Bach scholar, brought into a motion picture studio as a consultant. “This is the story of a woman who lost her first true love. It fees real because it is real,” says Minna to her boss Hilary. “The body was twitching after death. That when Elsa had the idea. What if Von Bach came back from the dead to save her?” The German Elsa Jagger is a stand-in for the English novelist Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, who in 1818 wrote Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus.

Von Bach inevitably returns to life, hidden in plain sight as a statue of what everyone thought was “organic resin”. When he does, and sees the panoply of motion pictures made out of his life, he is (figuratively) mortified. The cliche is that “only victors write histories”, but that should be expanded to Hollywood screen-writers. The most famous distortions of historical characters include William Wallace (and his relationship with Isabella of France) in Braveheart, Commodus in Gladiator, and the Scottish accent of the titular character in Mary Queen of Scots (she was raised in France and would have sounded French) and who in fact never met her half-sister, Queen Elizabeth I. Most particularly, if there was ever a case for defamation of the dead, we have the depiction of Alan Turning in The Imitation Game as someone suffering from blackmail by a Soviet spy. Little wonder then that one of the first things Von Bach does is bring defamation proceedings (the second piece of litigation within the title) as a consequence of the systemic besmirchment of his good name.

Mr Hammer deploys two interesting discrete structures to help tell his story:

- We count three separate sets of litigation in this title. We think that is a record within comic books, outside of the pages of Marvel Comics’ The Sensational She-Hulk (in which the main character is a trial lawyer). There is some verisimilitude to Mr Jagger’s representation of court proceedings which makes us wonder to what degree Mr Hammer has been involved in litigation. Von Bach, for his part, is self-represented in court as a consequence of his enhanced ability to speed-learn law and legal process. But he makes a tactical error. Allowing himself to be subject to cross-examination unexpectedly reveals that he has something to hide, and this is a thread which eventually reveals Elsa Jagger’s true fate. It is too easy to say that the recurrent litigation within Von Bach makes this a very Californian story. Instead, it seems to us that the structure of litigation, consisting of submissions and witness evidence, is a tight and effective means of communicating a story to an audience – which, after all, from a judge’s perspective, is precisely what a trial is supposed to do.

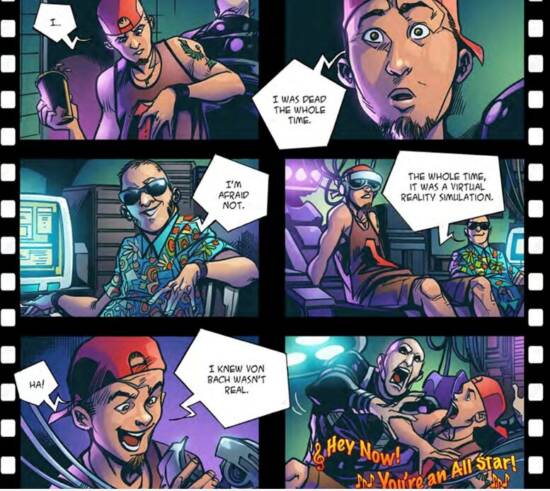

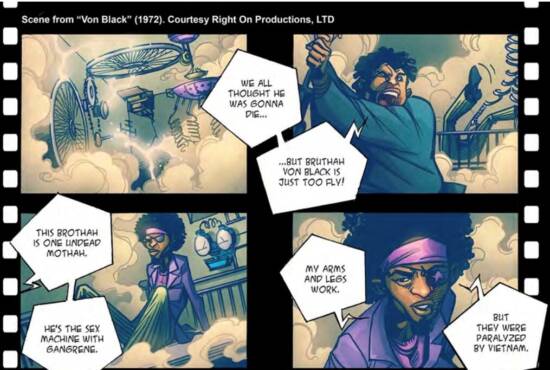

- The use of “video clips”. Like Frankenstein, Von Bach is described as being the subject of many, many screen adaptions – a hammy silent movie version (1921), a Keanu Reeves-esque version which the lead is barely scarred at all in order to preserve the attraction of his movie star looks (1993), a dreadful Blaxpoiltation version (1972), a very 1999 version featuring a tattooed slacker and a chirpy 90s music score (“Hey now, you’re an all-star”), a Laurel and Hardy pastiche, and so on. Each of these are interspersed throughout the story, usually to comedic effect. They provide interesting and funny micro mise en abyme:

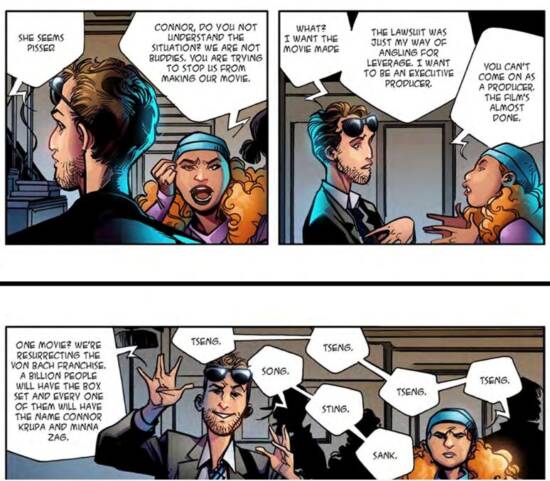

Prior to this, Minna meets the grandson of Inus Krupa, who starred in the classic 1940 adaption of Jagger’s novel. The conversation goes poorly: Connor Krupa as it turns out is a smug twit who also brings legal proceedings. When Von Bach comes out of his enamelled hibernation, Connor turns on a dime: suddenly realising that his leverage is gone, he shifts from being a happy litigant to being a smooth suck. Connor does have a redemption arc, of sorts:

According to both his preface biography and his LinkedIn profile, Mr Hammer works in the motion picture industry in Hollywood, and he loads that experience into this comic. Hollywood does not sound fun. “They already fired seven writers. Minna, they’re just going to throw you to the wolves.” But Mr Hammer draws out the industry’s ridiculousness, including the use of painkillers and stronger drugs as a mechanism for managing stress of being involved in the industry:

Hilary: “I think the pressure’s getting to you. Do you want a valium?”

Minna: “No.”

Peter: “Do you want some blow?”

Minna: “No.”

And earlier, when Minna is engaged to do the script re-write:

Hilary: “Let’s get you a MOU and a Taft-Hartley and a prescription for Xanax.”

Minna: “You’re serious. Hilary, I, uh… I should thank you for this opportunity.”

Hilary: “Save your energy. We start shooting on Monday.”

Minna: “You need a script by Monday?”

Hilary: “Don’t be ridiculous. We need it by Sunday. We have to make copies.”

Minna: “A completed screenplay?”

Hilary: “Put your life on hold, Minna. You’re going to be here twenty-four seven until the last shot. This is crunch time.” [moving to an air hockey table] “Gooaal!!”

Hilary epitomises misuse of authority in an insular creative industry where up-and-comers struggle to pay the bills and are readily exploited. She is otherwise jaded beyond belief: “Okay gang, this is a wrap for Laurence – our Von Bach. He’s played monsters, aliens and a guy with autism which is a tough role for a black actor – the studios don’t like a two-fer.” (We hope that people in management in Hollywood do not actually speak like that. But Mr Hammer pokes fun at his day job repeatedly, which makes us think they might.)

The pharmaceutical industry also does not escape Mr Hammer’s laconic eye. We bring a foreigner’s perspective on big pharma in the US. It is the most inherently contradictory of all industries in the American capitalist system. While endeavouring to create health solutions that help people, big pharma also wants to maximise return to investors without adequate policy intervention. We struggle with the concept. To a German medical researcher from the early Industrial Age, the tension between the two objectives are not just irreconcilable, but incomprehensible. Mr Hammer depicts his fictional pharmaceutical company, called Cal-Med, as a publicity-seeking circus run by clowns, which does not really know or care what it dispenses, and which hides behind disclaimers in advertising. (Visitors to America are universally baffled by drug companies’ TV advertising, which is one-part sales and seven-parts disclaimer, all set to imagery of aging people having lifestyle moments – quiet fun in parks and kitchens.) The motion picture industry looks conservatively sensible in comparison. Von Bach gets a job with Cal-Med not appreciating what a “celebrity endorsement” is: later, when he sues Cal-Med, and has the judge’s sympathy, Cal-Med’s lawyers is spontaneously offered a private research lab by way of settlement of the dispute. Quite the negotiated outcome.

About a third of the way through the story, the planned movie remake of “Von Bach” is falling apart, and the lead actor has dropped out. Minna proposes a Peter Cushing-style solution – Inus Krupa’s likeness will be computer-rendered. Mr Cushing’s likeness was repurposed for the role of Grand Moff Tarkin in the Star Wars sequel, Rogue One (2016). Rather amusingly, Mr Cushing’s most recurrent roles were as Baron Victor Frankenstein in Frankenstein-themed films in the 1950s, some of which were produced by Hammer Studios of London, a business apparently unrelated to Von Bach‘s writer. In Rogue One, Mr Cushing was “brought back to life” using a software platform called “facial action coding system”, and body doubles. Minna notes, “We’re bringing a man back from the dead to make a movie about bringing a man back from the dead. Totally meta.”

Intellectual property lawyers mused at the time of release of Rogue One about celebrity rights for the dead and their estates. Mr Hammer is no slouch on this concept, as articulated by Connor Krupa: “The character Von Bach is public domain… but according to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeal’s decision in “Krupa v Monster Models”, the right to derivative works of Inus Krupa as Von Bach is a distinct legal property owned by Krupa Enterprises. Me.” This judgment is obviously fictional, but the principle is correct. In the United States, unlike almost all other common law jurisdictions other than Jamaica, personality rights are capable of being owned by an estate. This reviewer (who is an Australian intellectual property lawyer) first encountered this concept in respect of Jeffrey Scalf’s use of legislation in Indiana to enforce inherited rights of publicity regarding his great-uncle, the famous Depression-era gangster John Dillinger. In California, where this comic is set, the publicity rights of the living are protected, but also Civil Code § 3344.1 protects the personality rights of the deceased so that the name, voice, signature, photograph, likeness of a person who lived in California or whose identity was used in California are locked down for 70 years.

What of the undead? California’s Civil Code is unsurprisingly quiet on the subject, but Mr Hammer’s fictional trial judge does not go there and instead treats Von Bach as a living person.

Mr Hammer’s work on characterisation is solid. Save for one alone, each significant player has a recognisable flaw which makes us believe they could be real people instead of sock puppets in a panel: Von Bach himself is aloof and subject to rage, Hilary and Connor are nothing but chipped and corroded machine parts within the motion picture industry, Bronwyn steals the identity of her friend for money, and even Minna wants to put the completion of the movie and everything that will give to her ahead of Von Bach’s revulsion of what that means to his name and reputation. The only character who is without blame is Elsa. But she is far from a sock puppet. Elsa initially gives the impression she is but a pneumatic love interest to Von Bach. But she is a proto-feminist who is not prepared to let her female first name stop her from being a writer. She wants justice for Von Bach’s murder, prepared to deliver it herself if she must, and she wants to clear Von Bach’s name because it is the right thing to do. Long dead, she is the hero of the story.

At 162 pages, broken up into various chapters, the online version of this comic is not something we would normally critique, because doing a respectful review of a publication of this size diverts us from other critiques. Von Bach the comic is a significant fleshing out of the original work – a stage production. Von Bach has been staged three times in Los Angeles. At the end of the story are some photographs of the production. We would have liked to have watched it. Without the opportunity to do so, we are content to enjoy this clever, genuinely funny, well-crafted comic.