Writers: Tom Peyer and Paul Constant

Artists: Jamal Igle, Juan Castro

Ahoy Comics, collected May 2019

The “nature/nurture” debate has been the fodder for various superhero genre titles over many years, especially as creative teams began to explore “What if…?”, “imaginary stories” and later, “Elseworlds” within the well-plumbed continuities of major American publishers. In Marvel Comics’ Uncanny X-Force #11 (2011), written by the masterful Rick Remender, an evil, alternative universe version of a superhero called Beast waves his hand at a portrait on the wall of his laboratory. Depicted are some members of the mutant superhero team the X-Men, but, like the Beast, raised in a grim ideological environment where mutants reign supreme and racial impurity is purged. They were shaped by their alternative Earth society to become, in essence, super-powered Nazis. “Answers the nature/nurture debate,” shrugs the Beast.

We have previously reviewed The Wrong Earth #1 https://worldcomicbookreview.com/2018/09/23/the-wrong-earth-1-review/and found it to be an entertaining frolic. With the collected first four issues, it has become clear that the creative team of writer Tom Peyer and have masked a quite serious exploration within a story about genre themes.

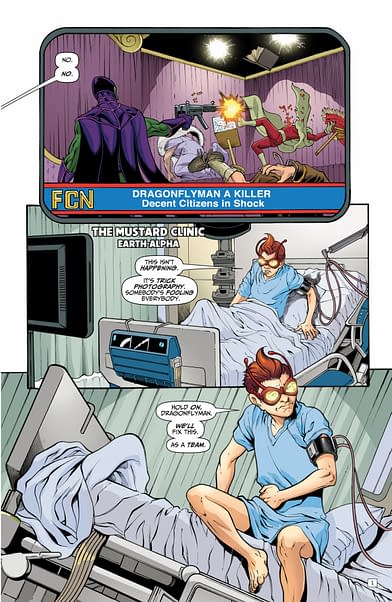

The protagonist is called Dragonfly Man on one happy, goofy parallel universe Earth, and Dragonfly on a grim, gritty alternative Earth. Dragonfly Man is plainly styled on the camp and wacky television version of Batman which was very popular in the late 1960s. Dragonfly is based on the hard-edged Batman of the 1980s and forward, rendered by writer/artist Frank Miller with his comic, The Dark Knight Returns, furthered by Alan Moore’s serrated The Killing Joke. Many other reviews of this title have looked at the stark contrast between the two characters and what that signifies about the overall descent of the superhero genre into shadow. The contrast is meticulous: for example, Dragonfly Man keeps trophies to help him to remember, and Dragonfly keeps a bottle of spirits in his filing cabinet in order to help him forget. Dragonfly Man merrily outwits foes with outlandish gadgets “of my own devising”, but Dragonfly grabs an adversary’s machine gun and, without pause for thought, shoots the mostly harmless thief Triviac in the head with a machine gun on national television.

And it leads to a question. Was the radical thematic shift of Batman in the 1980s and all those gun-toting militarised characters and titles that followed in the late 1980s and 1990s, and thereafter – The Punisher; Cable and Domino in Marvel Comics’ X-Force; Bishop in Uncanny X-Men; Stryker and Ballistic in Image Comics’ Cyberforce; Wetworks; Bloodstrike; War Machine; and so on – merely a new perspective on a tired concept, or did the ongoing bleakness and gun-glee of superheroes become lazy writing?

Or did it reflect the zeitgeist both before and after The Dark Knight Returns? As this Baltimore Sun article https://www.baltimoresun.com/news/bal-te.pentagon08jun08-story.html notes, “Between 1980 and 1985, the number of dollars devoted each year to defense more than doubled, from $142.6 billion to $286.8 billion. The Navy increased its force from 479 combat ships to 525, while the Army bought thousands of the new Abrams tanks and Bradley Fighting Vehicles. An Army attack helicopter called the Apache, a key weapon in both gulf wars, made its debut.” At the height of President Ronald Reagan’s build-up in military spending, the defence budget was colossal, exceeding 6.5% of the United States’ GDP. This was a spend that could not be ignored. It was carried by American businesses and households. Coinciding with that, we see the emergence of popular titles like G.I. Joe, Alien Legion, Jon Sable Freelance, and Judge Dredd.

Dragonfly Man has a cannon mounted onto the roof of his cruiser, like Batman in the Dark Knight Returns. The only thing missing is multiple ranged weapons improbably strapped to his back a la the Punisher or Cable. The 1966 wackiness might be more fun, but the creators of The Wrong Earth revisit the gloomy spirit of the 1980s with gritted teeth.

The parallels between the characters and their very obvious inspirations are the preoccupation of most reviews of this title. What has not be considered, as far as we can see, are the differences. Plot aside, Dragonfly and Dragonfly Man are not the same person. They may be biologically identical, but what we see here is that, contrary to the conclusions in X-Force, nature wins out over nature.

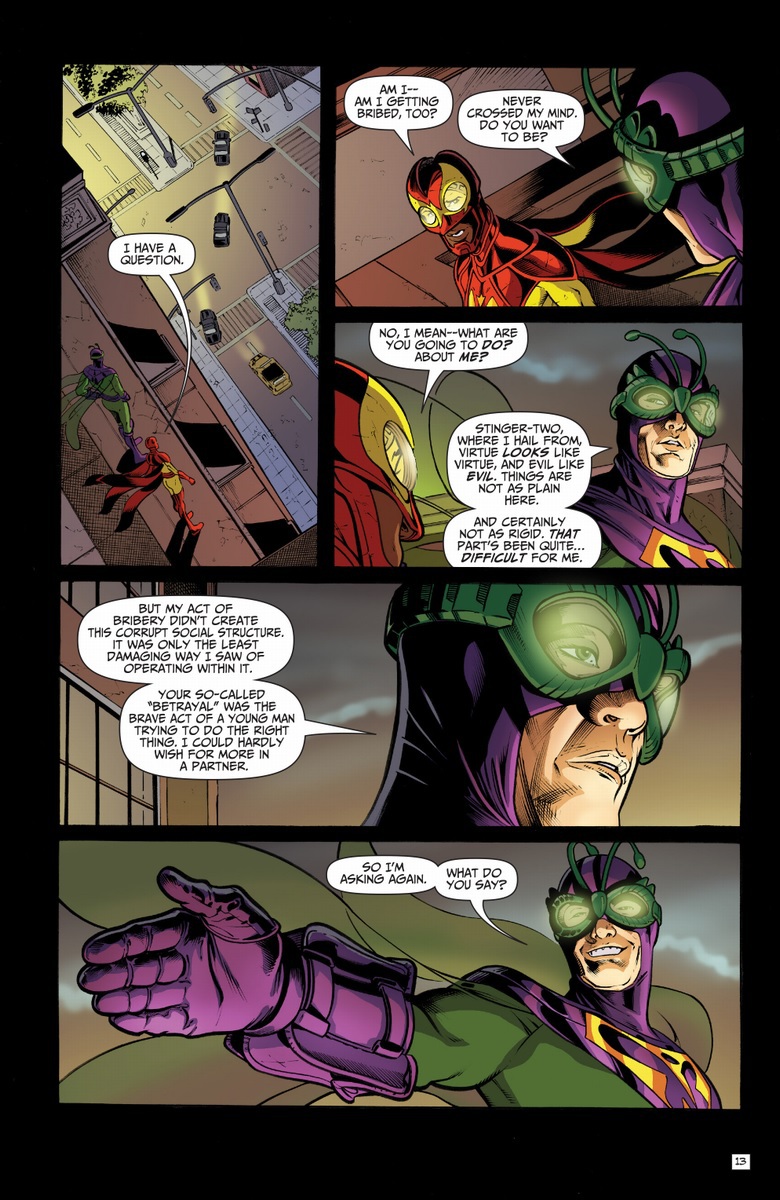

Dragonfly Man is put through the wringer when he drops into the dark and brooding Earth Omega. Corrupt cops, psychotic murders, and the unprovoked malice of strangers wear him down. “That part’s been… quite difficult for me.” But, despite bouts of despondency, he stays true to his moral compass. The new environment of Earth Omega does not change him, and while he understands what he faces, he does not adjust to it. Fundamentally, Dragonfly Man is a good man, even when surrounded by evil things.

The same cannot be said for Dragonfly.

Dragonfly is now in an environment where there is no need to do bad things. Genuine danger and evil do not exist in Earth Alpha. There is no gasping for air, the adrenaline trickle of imminent murder or torture, the knowledge that everyone – everyone – hates you or fears you, and wishes you dead. Dragonfly is in a position to turn a new leaf. But he is true to his nature. He cannot. Fundamentally, he is an evil man who on Earth Omega, fights men more evil than himself.

There are unexpected depths to consider in something so fun – even so obvious – as an Adam West-themed/ Frank Miller-themed crossover.