Lightstep #1 v Druuna (comparative review)

Dark Horse Comics, October 2018 (Lightstep)

Metal Hurlant / Dargaud / Bagheera 1985-2003 (Druuna)

Writer:

Miloš Slavkovic (Lightstep)

Paolo Serpieri (Druuna)

The idea of a human exodus from a ruined Earth is something long explored by science fiction writers. Generation starships are ecosystems within which to explore lost human purpose, a destruction of civilisational norms, lawless horror, and other aspects of dystopia.

Most comic books prefer the action of near instantaneous transition across space: faster-than-light hyperdrives or interstellar portals are the usual mechanism for conveying characters to other worlds. Slow moving ships taking tens of thousands of people to colonise distant planets do not have the immediacy of transition that we have become used to as a consequence of Star Wars. Spacefaring superheroes in American comics do not take long and slow rides to far-flung star systems: they instead whizz about in spaceships no bigger than family cars. Slow moving generation ships provide in contrast an ideal landscape for exploring sealed worlds of flawed utopias (see our previous review of Dark Beach) and horrible mutations.

Europe has a strong tradition of science fiction comics, best exemplified by 2000 AD’s Judge Dredd and Rogue Warrior, Alejandro Gotorowsky’s The Incal (which we have previously reviewed and which was published in the legendary Métal hurlant, by Les Humanoïdes Associés, France), Pierre Christin’s Valerian (which we have also reviewed) and Mœbius’ Le Garage Hermétique. Some of those titles are darkly dystopian.

In this comparative review, we look at two science fiction comics which we regard as European: the French Druuna, and the American-published but Serbian-written Lightstep. Lightstep has just been published: Druuna concluded publication fifteen years ago.

Druuna

Druuna is a cult classic science fiction comic featuring hard core erotica. It first appeared in France in 1985, and has been, commercially, extremely successful

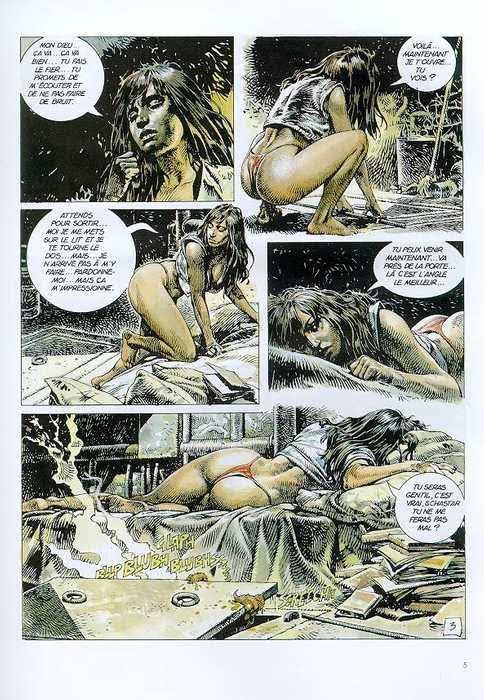

Somewhat disingenuously, Paolo Serpieri, the writer and artist, was quoted in the forward to one of the volumes that the title character’s promiscuity was an expression of sexual liberation. The reality is that Druuna, a young woman living in a dystopian future filled with disease, brutality and poverty, is a frequent non-consenting victim of sexual assault, and is portrayed as a malleable object of desire to a male readership. Druuna’s sexual adventurism and the repeated sexual assaults inflicted upon her are illustrated in very explicit and occasionally horrific detail throughout the duration of the title.

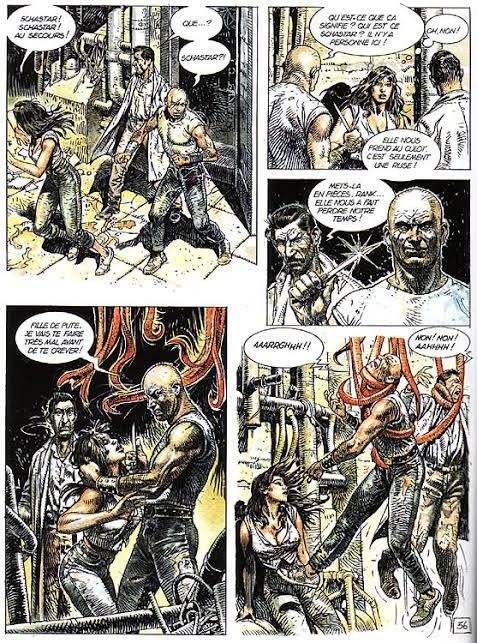

Yet there is something to the plot of the story which is very compelling. There is nothing but desperation and serious trouble confronting Druuna at every turn. Druuna’s efforts to save her friend from the onset of his disease invoke themes of corruption, police brutality, and gang law. In the very first story, Druuna prostitutes herself to a doctor in order to procure medicine for her partner, Shastar. Living deep underground in a place called The City, surrounded by the hideous victims of a teratogenic morphological illness called Evil, Druuna eventually makes a remarkable discovery. She along with everyone she has ever known are actually on a starship which is lost in space.

The original Alien motion picture by James Cameron has spawned many movie sequels, and many comics. We have previously reviewed two of these: Alien: Defiance , and William Gibson’s Alien3 screenplay which we noted has been recently adapted as a comic book. The horror of the Alien comics (and indeed the motion pictures) relies upon:

1. the disturbing visuals of the xenomorph, first designed by H.R. Giger and their effortless, relentless hunt of humans. The hunt is motivated by something other than a desire for meat. Humans are used as incubators for offspring, a particular horror as the humans are alive and conscious during that process; and

2. The slowness and isolation of the starships which convey the victims of the xenomorphs through deep space. That isolation works well in that it seals off escape from the horror: there is no quick rescue at hand, and no imminent arrival which might provide . Hopelessness prevails, and survival uncertain.

Druuna taps into much of that sense of creeping horror and desperation.

The monsters that haunt the ship, human and otherwise, without a second thought are willing to rape and kill Druuna. The sufferers of Evil are portrayed as tentacled monsters who stalk and kill their victims. The ignorance of the population to the parameters of their existence, living on a slow moving starship with no effective crew and martial lawlessness, adds to the feeling of doom. When Druuna (through her meandering adventures involving suspended animation) does make it to Earth, she finds that the planet has been scorched in a war between humans and machines. There is no hope at any point. It is a terribly bleak future for our descendants.

Lightstep

Lightstep is a comic which has successfully transitioned from being a Kickstarter production to be a publication of Dark Horse Comics. Dark Horse Comics’ solicitation reads:

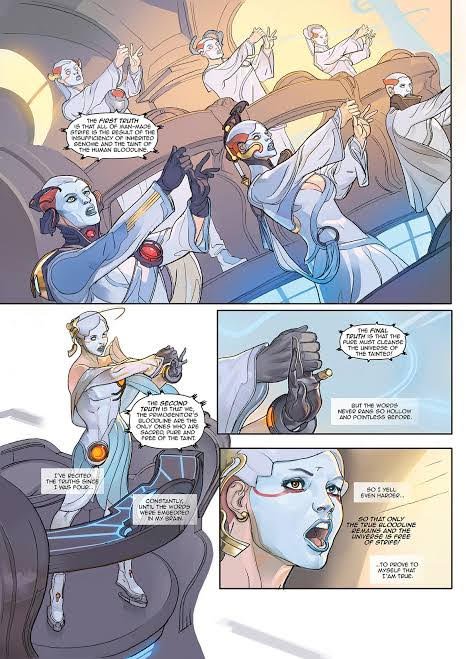

“Lightstep is about a galaxy controlled by a race of elevated beings who live out their lives on accelerated ‘Lightstepped’ planets – where a single day spans a lifetime on other worlds. Lightstep follows January Lee, a woman of royal descent, whose ‘divine illness’ reveals to her the lies of her ancestors who founded the empire. Banished from her home into the void, an unexpected rescue sets January on a course to redeem her heritage and change the galaxy forever.”

The title contains echoes of HG Wells’ The Time Machine, with its evolutionary divisions between the oppressed and the apex of society. In the case of Lightstep, though, these divisions are the product of a eugenic breeding program in which the surviving brother of a triumvirate has perpetuated his lineage for generations within a smug and languid class of rulers.

The basis of the society has its roots in decadence: “never-ending orgies” produce children, as does advanced genetic technologies.

The writer, Miloš Slavkovic, takes us at breakneck speed through the history of this culture. It is very hurriedly executed in this first issue, but it is fascinating.

The division between workers and their rulers is accentuated by the use of generation starships. In the case of the rulers, the ships move fast. As Einstein’s theory of relativity tells us and as is recounted in the story, the closer to the speed of light you travel, the slower time goes. The elite in this future society have “extended” lifetimes that are the equivalent of generations of those living in less speedy ships.

(We query a plot hole: whether the elite would notice their absence of aging given they are all living at the same speed as each other. Their relative immortality would only be apparent when meeting someone from the lower echelons, which according to the story they would never do.)

The protagonist, January Lee, is one of the elite. But she does not buy into the philosophy of her class.

January refuses to take part in a murderous ceremony which requires her to gut her insipid younger brother. January is exiled, cast away from her fast-moving home and into the “outskirts of hell” in deep space.

Within Lightstep we have a very different take on generation ships. They are used to prolong the lives of the elite, who spend their lives without real purpose. Everything is perfect, including the ceremonies of human sacrifice to legacy. It is creepy in a less visceral way from Druuna: here instead, the happy and genetically pure spend their days in dappled shadows on manicured parks, occasionally engaging in ritualistic beheadings and incineration of outsiders who do not fit the genetic norms.

Both titles in our view are very European in their dour assessments of the future. Indeed, Druuna and Lightstep are different sides of the same coin. There is horror and death. There is sex, but not love. There is a truth, but it is difficult to perceive. And both bleakly suggest that if humans eventually explore space, we will very likely take our deep flaws with us.