Batman: The Dawn Breaker #1 v. Batman: The Drowned #1 (comparative review)

DC Comics, March 2018

Writers: Sam Humphries (Batman: The Dawn Breaker) and Dan Abnett (Batman: The Drowned)

American comic book publisher DC Comics is presently rolling out a new collection of Batman-themed titles. These comics are predicated on the idea that variants of DC Comics’ main superhero character, Batman, exists on parallel worlds, and that some of these variants are fearful killers.

The Bat Multiverse

DC Comics has for decades relied upon the idea of a multiverse to corral all of its various properties in circumstances where the characters could not sit comfortably in the one existence. It has been a useful mechanism to divide vastly different fictional realities. DC Comics tried to erase the divide in the multiverse-collapsing epic Crisis in Infinite Earths (1987) but in recent years has drifted back to the idea of a multiverse to harbour its competing plot lines.

The particular parallel worlds featured in these two titles, however, are somehow substandard to others. In these two issues, Batman: The Dawn Breaker is set on a parallel Earth given the nomenclature “Earth Negative 32”, and Batman: The Drowned is set on “Earth 11”.

Attributing numeration to alternative universe variants of the Earth has its pedigree with The Flash #123 (September 1961), which introduced “Earth 2”, a parallel world filled with fictional characters which had featured in various comic books published during World War Two. Curiously and having regard to the theme at hand, on Earth 2, in Adventure Comics #461, published March 1979, Batman died in combat and his role was taken over by his daughter, named The Huntress.

Others variations of the Earth, and Batman, followed over time. These two Earths however are new to readers.

Bat Amalgams

Batman is a grim but altruistic crime-fighter typically portrayed as relying entirely on his genius, cunning, relentlessness, and some very clever technology. However in each of these issues Batman is depicted to have adopted superpowers. These superpowers are thematically associated with Batman’s allies. Thus, in Batman: The Red Death #1 (which we have previously reviewed) Batman has appropriated the powers of his friend The Flash. In Batman: The Murder Machine #1 (which we have also previously reviewed) the character’s transformation into an emotionless, AI-enhanced killer involves the skills of Batman’s colleague Cyborg.

In the two comics we consider in this comparative review, alternative universe Batmen (“Batmans”?) have again acquired superpowers with the themes linked back to other DC Comics’ characters. DC Comics thus engages in a systemic iterative fusion of its characters, each with malevolent intent, to propel the plot.

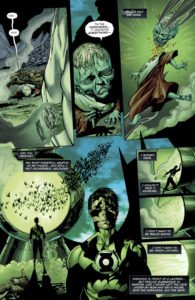

One version of Batman is depicted as wielding the power ring of a Green Lantern (an intergalactic police force which we have previously discussed) . Batman has subverted the ring to darkness through sheer will and a crushing lust for vengeance against criminals. This is a perverted re-casting of a story by writer Mike W. Barr in 1994, entitled Batman: In Darkest Knight which features an alternate universe Batman becoming a grim but ultimately altruistic Green Lantern.

The other title, set in a universe with gender-reversed characters, features a female Batman performing genetic experiments on herself so as to adopt the deep sea characteristics of the inhabitants of Atlantis. The purpose of doing this is to better defeat them. This female Batman uses a trident to skewer a female version of Aquaman (a super hero who lives in the ocean, and who is depicted as a long time associate of Batman). She resembles a drowned corpse, with a face of rotting scars, and wears a very steampunk-themed costume. It is a very different iteration of Batman.

Writer Without Fear

Having broadly explained the plot of these new Batman titles, we turn now to the skills deployed by each of the writers in each respective title. Batman: The Dawn Breaker is quite horrible. Upon introducing the title character as a child, the reader watching Batman’s parents killed in the famous sequence which leads the character to eternally wage war on crime, writer Sam Humphries is not afraid of communicating to readers that he barely tried to write with any creativity or lucidity:

“When I stood there helpless while my mom and dad’s blood was running into the gutter? I felt… nothing. Like the sky and the ground broke apart and all that was left was a void as big as everything. And that void was inside me. I didn’t feel anything. Not even fear.”

And when the youthful Batman commands the ring to kill Joe Chill, the murderer of Batman’s parents, for unknown reasons the power ring begins to verbalise an mathematically impossible calculation of Batman’s willpower. How can a man have willpower of 181%? 181% of what? Setting aside this ridiculous notion, if the idea was to portray Batman’s formidable will as capable of overriding the power ring’s built-in prohibition on lethal force, this could have been achieved with nuanced, sparse dialogue. What we see here instead is painfully telegraphed.

Batman goes on to incinerate Police Commissioner Jim Gordon when Gordon reveals that he knows Batman’s real identity. Gordon’s skeleton writhes in the green fire. It is an exercise in teen schlock horror. Batman then does the same thing to several alien Green Lanterns who have been commissioned to bring him to heel, as well as some of the Green Lanterns’ overlords, the Guardians of the Universe. More burned skeletons litter the panels.

Then, for reasons unknown but presumably related to the defective nature of that universe, the Earth falls to pieces, leaving only rubble in the dark. We assume this is a consequence of Earth-11 being subordinate to the other universes and part of the broader plot between the titles.

Floating in the void, Batman is then recruited by another Batman, this time a Batman amalgamated with his arch-nemesis, the evil Joker (called “The Man Who Laughs”). We have previously expressed our concerns over this very dubious character.

The title Batman character then somehow pops up in a fictional American city called Coast City located on Earth-Zero, DC Comics’ main Earth. Flying in, this Batman / Green Lantern composite pauses to deface a road sign. It reads, “Welcome to Coast City: The City Without Light”, the word “light” scrawled onto the sign in blue paint by Batman.

Having killed a police officer and killed various Green Lanterns, Batman has now stooped to graffiti. From beginning to end, the title is an immature nonsense. Mr Humphries should both have anticipated and feared such derision.

Whispers of the Devil

In contrast, the monologues in Batman: The Drowned is compelling and weighty. Here, the gender-switched Batman (who we shall call The Drowned to avoid confusion) engages in brutality and self-harm to win a war against Atlantis. The promise of violence inherent in superhero comics is thereby fulfilled.

But the text repeatedly draws a parallel between the view of a deep water swimmer looking up to the light, and a fallen angel looming up at heaven from the vantage point of hell. The introductory monologue is mournful and angry at fate:

“The only world I’ve ever known sinks back into the darkness below me forever. As does the only love I’ve ever known. But Sylvester dies a long time before my world did. I fought hard to cling on and keep it afloat after Sylvester’s death. But it couldn’t be saved. It’s time to let go. To accept. And go up… toward the light. The damned light. The mocking light.”

This could be a passage from John Milton’s Paradise Lost (1667) where the angels who rebelled against God are cast down into the pit and look up at Heaven. It is entirely devoid of cliche. This theme continues to the end of the issue. When The Drowned is recruited for mayhem in a similar fashion as the Batman/Green Lantern character, the honeyed words of a devil spill from the Batman/Joker composite’s lips:

The Man Who Laughs: “But it’s not really your fault. It’s the light, you see… the light up there.”

Monologue: “And he showed it to me. He showed me the lower-tiered worlds. The minus realms of the dark multiverse that had suffered so that the light could thrive. The worlds and the peoples who had paid the price so that the worlds above us could flourish. And he showed the others like me. Outcast iterations. Dark echoes of a man who had taken it all. And he laughed.”

The Man Who Laughs: “You see the light up right there? … it mocks us all. It’s an unsullied multiverse where all is bright and ascendant. It’s why we suffer. It’s why nothing can ever be made right. That world is the perfection you dream of. You are it’s nightmare.”

Inner Monologue: “”Think of drowning,” he said. “It’s both active and passive. Don’t be the victim who drowns. Don’t sink with the rest. Be active. Rise up… reclaim the light. And be the one who does the drowning.”

Again, this is Miltonian: these could be the words of Lucifer’s lieutenant Moloch from Paradise Lost, advocating to the fallen angels an “open war” against the host of God.

In Batman: The Dawnbreaker, The Man Who Laughs offers the return of Batman’s parents as incentive to kneel in subservience. It is a cheap card to play, and with no assurance that The Man Who Laughs can deliver what he promises.

But, in contrast, in Batman: The Drowned, The Man Who Laughs offers existential purpose to a bleached corpse-like demon who is lost in her submarine depths of despair: vengeance against those who live in a paradise barely visible from the depths, vengeance against those who will survive in a bright and warm celestial sphere when others died in darkness.

It is sophisticated, a term we would not ordinarily use to describe a Batman comic, and a credit to writer Dan Abnett.

Comparative Review

This is the first time we at the World Comic Book Review have engaged in a comparative analysis of two related works. Our conclusion is that there is no comparison. One story was penned with finesse by a seasoned writer. The other is a series of childish embarrassments.