Writers: Arnold Pander and Zero Boy

Artist: Arnold Pander

Dark Horse 1997

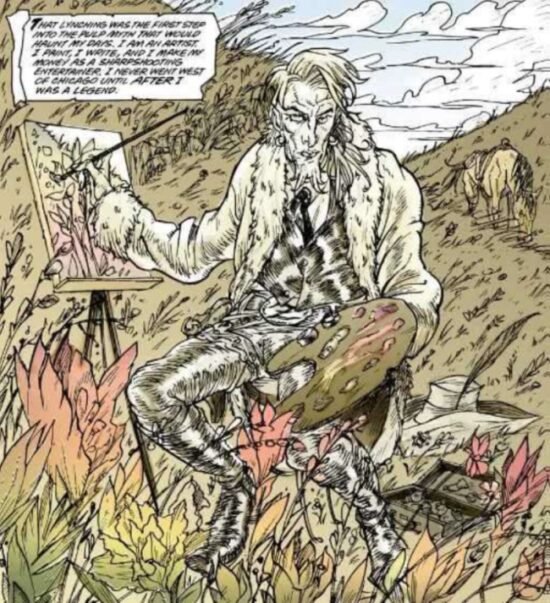

WHAT A DELIGHTFUL YARN, watching artist Arnold Pander spin himself into a Wild West legend in layers, telling us who his designated hero Jack Zero thinks he is, and who others think he is; not a sensitive artist who paints and makes a living as a sharpshooter showman with skills honed by gigs with Buffalo Bill, Annie Oakley, and Wild Bill Hickok him- and herselves, respectively, at sideshows back East; no, the legend says he is a dead-eye killer who saves poor virtue in peril, and unsaves a lot of others. He helps tame the West. His fictional deeds are celebrated in pulp adventures as the gospel truth.

When I discovered JACK ZERO in a colorized digital version online, I had to find the original pulp version that appeared in 1997 in five parts in Dark Horse Presents (#121-125), an anthology title published conveniently close to Arnold Pander’s western abode. Once my stack was complete, I zeroed in on Jack.

The mismatched stories of Jack’s real self and his fictional selves intertwine in the telling, until gradually the legend of Jack Zero bleeds to the surface. He meets a woman and is pulled westward, and he packs both guns and paints. The artist himself hovers nearby.

Arnold Pander’s black-and-white penwork moves and charms, evokes and thrills; like journeys in verse or song, it occurred to me, or a holiday adventure in an exotic setting, where it matters little where you go, because every direction pleases along the way. The story, co-authored by Arnold Pander and Zero Boy (a suspicious pseudonym), is equally charming and evocative. The parts weave together simply and steadily to the point, inevitably, where blood flows. The layering of meta-story upon meta-story, with the artist at the apex, casting reflections on his own existence in the Wild West, weaves a pathos into the tale that bleeds into real experience, much like the layered and serried art. In the digital version, the added washes of color have a similar layered appeal that reaches outward.

A love story, a love triangle, danger and doom, all nicely portrayed; and a recognizable encounter with the Wild West, when Jack arrives in an Oregon landscape of stumps, once a vast, dense forest. The railway Jack arrived on gave skyline logging in the Pacific Northwest a precipitous boost. In this place on the far frontier, local tyrants were common: people with power and patronage to accomplish great things in whatever small or large setting they happened to be. In Oregon, no tsar or other empire grandee controlled the commerce of all the realm. Any government was scarce, and what existed was easily corruptible. The spirit of American enterprise allowed any who could by the power of capital as the basic influence to contract and bully workers into industrial plunder of land and resources, there for the taking (ah progress), enabled routinely by legislators, judges, politicians, and editors to achieve the fine civilization they inhabit today.

The Jack Zero tale tells it all, something like this, in far fewer lines. The fictional and nonfictional layers in the past skein toward the future in his life, subject zero, and twine into ours.