Creator: Shigeru Mizuki

First published in in Japanese in Kodansha magazine Shukan Gendai, 1973

Published in English by : Drawn & Quarterly Year : 2018 (first publication 2011)

There are not many people left who fought in the Second World War. One day (not too far in the future) there will be no one left to tell what happened in those trenches, beaches, deserts, and vineyards. The only way we can hope not to lose their voices is by asking them to record their individual stories.

There is, nonetheless, a question we need to ask ourselves: what is the purpose of having people tell us what happened on the battlefields? If the idea is simply to know what went on during those days, having people repeat the same stories with minor changes in their details (we waited, we shot, we killed, we won or we lost) is more of an exercise in style than in meaning. There must be something more, then, to just writing down on paper a series of events, whose interpretation cannot be left as a matter of personal choice.

Shigeru Mizuki’s anti-war graphic novel, Onwards Towards Our Noble Deaths therefore, focuses not only on the horror of war, but also on war as seen from a new point of view, that of those who would later lose: the Japanese. As the author states in the interview (it can be found at the end of the book), the story here told is not fiction: 90% of what we see, Shigeru says, really happened. Memory plays the role of truth, as the writer/artist asks us to listen carefully to what he has to say, never taking the position of someone who wants to give a blunt final judgment over what happened in those days in South-East Asia.

Whatever we are to make of it, so the novel seems to imply, is something that should come out of our own pondering over what we are reading.

Mizuki, in fact, does not intrude into the flow of the reading as to highlight what his stance is. Instead of stating the problem, he prefers to show what really happened so that our response is natural, not guided by another person’s (the artist’s) own preconceptions.

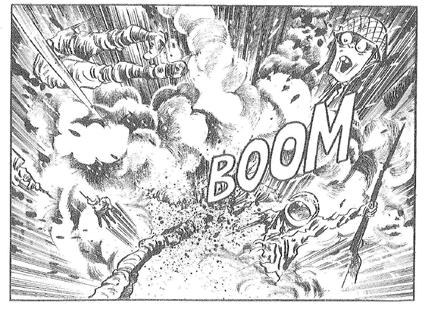

If war is Hell, this is not something we realize because we are being told so, turning us into passive spectators; the uselessness of any kind of carnage should be a conclusion we come to because we take an active role in the interpretation of the events unfolding in front of our eyes.

The dialogue that comes into play, then, is such that instead of simply focusing in the “feeling” that we get from the pages (the feeling of anguish, despair) we are led to actually think and ponder. We, the readers, are not just looking at a series of scenes in black and white; what we are doing is try to make sense of the underlying question of “what is it all for”, where “it” refers to two interlocked matters: the matter of what war memories are for, and the matter of what war means for us human beings.

The point of view that is taken, moreover, is usually that of the lowest creature on the battlefield, that of the soldiers whose importance lies simply in their numbers, depriving them of any kind of individuality. Yet, such individuality is what interests Mizuki, as each soldier represents an entire world, a series of relationships that there, at the front, are reduced to the sad longing for a time (peace) that does not exist anymore and that seems so far away from their present situation.

About two years is the time spent on the island of New Britain, from 1943 to 1945, and what we gain from this experience is the tragedy of life being treated as a commodity that can be bought and sold. Death, the natural outcome of war, seeps through the pages, making us wonder from the very beginning what fate awaits the soldiers we learn to know, even though we know, subconsciously, that no happy ending is here possible.

If war is useless, then, so is the sacrifice of men who marched on towards a glory which hid, behind a veneer of medals, the tragic face of emptiness.

We are all part of the same race not because we are divine creatures, but because we are mediocre animals who try to survive by finding what little joy life can give us.

Our right to live is not a universal right that cannot be broken and trampled on; war, indeed, shows us how such a right means nothing when the rules of the game are changed by a homo homini lupus context.

What we need to make sure is that such wasteful carnage cannot happen again. Memory, then, is our only way to be vigilant, and such memory is what makes Onward Towards Our Noble Deaths a work of art that asks us never to fall prey to the same mistake over and over again.