Writer/Artist : Rumiko Takahashi

Shogakukan, 1980-1987

English Edition : Viz – Collector’s Edition

Translator : Matt Treyvaud

Love, as a topic in literature, usually means that there is someone who loves somebody, which leads to the fact that there must be something that prevents them from being together. If, in the end, they manage to become a couple, the ending is uplifting. But if they are separated forever, it all becomes a tragedy (William Shakespeare amongst many others has much to say on both states of affairs).

It is the duty of a master narrator, then, to make sure that all fits perfectly so that we, even though we kind of know how it is going to end, find ourselves more than simply interested in seeing the way the story unfolds. In other words, once tragedy (or something similar) is taken out of the picture, the remaining structure, the one that sees everybody led to a happy ending, should not be written as a “taken-for-granted” obviousness.

It is, after all, the interplay between knowing what the end is going to be and, at the same time, not being completely sure about it due to the writer’s masterful strokes (Are they or are they not going to? Of course they are, but are you sure?).

It is here, then, that Rumiko Takahashi’s Maison Ikkoku manages to shine as one of the best romantic comedies of all time. Set in modern times, drawing inspiration from part of her own experience when living in a house with a bunch of odd tenants, our author weaves a story that, in its simplicity, manages to have us turn page after page in a frenzied state of wanting to know more.

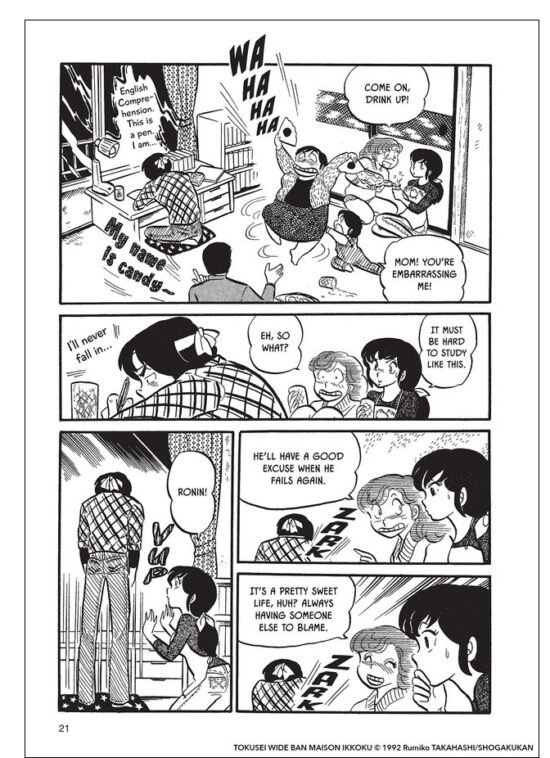

The question of whether the two main characters are going to end up together, a third person being the necessary antagonist, does not shy away from those very problems that make us understand that things are not (neither can they) be so simple. The trite topic of there being a series of obstacles, therefore, is here presented in a deeply realistic shape. It leads us to a realization of the difficulties that pile up, one after another, on the way towards happiness.

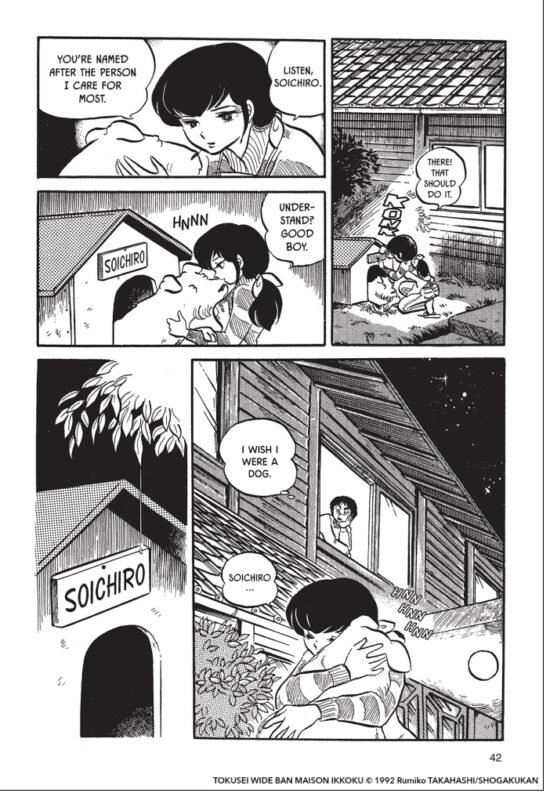

It would nonetheless be reductive to state that Maison Ikkoku is simply a love story for adult readers. Once the main topic is taken apart, dissected and analyzed into its components, there remains a plethora of details that all concur to the development of a series of considerations regarding the art of narration. Each character, then, be they one of the tenants or a member of our main characters’ family, is given enough space and depth so to infuse a sense of realism into the story. Even the dog itself, bearing the name of the female protagonist’s dead husband, becomes part and parcel of a tapestry of adventures and misunderstandings.

The simplicity of the story, then, taken in its barest form, undergoes a series of interplays that highlight the nature of the “will they or won’t they?” structure. This is typical of any good narration that tries to instil in their readers that kind of curiosity that has them going back to it. That is not just in regards to the very act of reading, but also to that of remembering, of finding a certain kind of sweet solace in letting the stories we have been experiencing as spectators come up into our mind. They make us feel better about ourselves and the world around us. A fantastic piece of literature, Maison Ikkoku is perhaps Ms Takahashi’s best work.

An interview with Maison Ikkoku’s translator, Matt Treyvaud.

WCBR : Maison Ikkoku is still one of Rumiko Takahashi’s best series (if not “the” best series). What would you say is the reason for such love and respect from its readers?

M. T. : I don’t know if there is a single reason, but I think the (relatively) realistic setting and love story with actual forward motion and a satisfying ending are both a big part of it. Obviously very few people have experienced exactly the kind of relationship it depicts, but the emotional threads of the story are hugely relatable—struggling to figure out who you are and what you really want to be, learning to be vulnerable and trust people again after heartbreaking experiences, and so on.

WCBR : Would I be wrong if I said that Mison Ikkoku still resonates with the Japanese? Is the culture of today’s Japan the same which we see in Takahashi’s graphic series?

M. T. : I think for Japanese readers there is a certain nostalgia there. The manga started in 1979, the year the Walkman was invented. So it depicts Japan just before the bubble and before it had this international image as a high-tech wonderland. There aren’t many apartment buildings like Maison Ikkoku still around anymore. And Mitaka’s apartment is a wonderful time capsule!

Still, a lot has also stayed the same—the pressure on kids to get into college, and then to get a good job, and old-fashioned family expectations. Again, even if the specifics have changed a bit, and there is more freedom than there used to be to take a different path if you’re determined enough, it’s still relatable.

WCBR : How easy or how difficult would you say it is for a western audience to understand the nuances of the series? Are the cultural differences many or just a few? I refer, for example, to the importance of going to university so to find a job as a salaryman, or the problem in getting into a university.

M. T. : I hope that the translation conveys the necessary nuances! At times when it seemed there was just too much background knowledge needed to fit in the dialogue, we resorted to cultural notes at the back. I suppose there are some things that readers unfamiliar with Japan might not get—for example, what the mood is at a small local festival, or what kind of outing it would be for a Tokyoite to drive to the beach in 1980, or exactly what sort of social expectations Kyoko is dealing with as a young widow. But ultimately, the heart of the manga is Godai and Kyoko’s story, and I think that Rumiko Takahashi is such a master of characterization (through interaction) that their emotional journeys and personal growth come through quite clearly.

WCBR : Have you found any problems while translating the series? Is there anything that cannot but get lost, when you move from Japanese to English?

M. T. : There is always something, alas. In the case of Maison Ikkoku, one thing Japanese people remember very fondly is Godai referring to Kyoko as “Kanrinin-san” (kanrinin meaning ‘manager’ or ‘superintendent’). But it doesn’t always feel natural for him to, for example, call out “Manager!” in English. Everyone will have their own opinions about things like this should be handled. Rumiko Takahashi is a master of screwball comedy involving misunderstandings or wordplay, and those were very difficult to travel on a nuts-and-bolts level.

The editor and I have both loved this series for a long time, so we did our level best to be faithful to the original while still ensuring that it moves English-speaking readers decades later in the same way, whether by making them laugh or making them cry.

WCBR : You live in Japan and you speak the language. Would you say people nowadays are reading more or fewer manga than in the past decade, there? What kind of manga (I refer mainly to their genre) are the most successful?

M. T. : It’s hard to say from impressions on the street. I go to my local bookshop all the time, and its manga floor is still going strong! Despite competition from other forms of entertainment like social media and mobile games, I believe that manga sales are still going up, driven by e-books. I suppose that it is easier than ever to just buy something to read if you happen to be bored on the train with your phone handy.

While the “most successful” genre in terms of sales is still action-based series like Demon Slayer (Kimetsu no yaiba) and so on—at least last I heard—it also seems to be easier for manga artists creating more narrowly focused stories to find an audience online and grow their following that way.