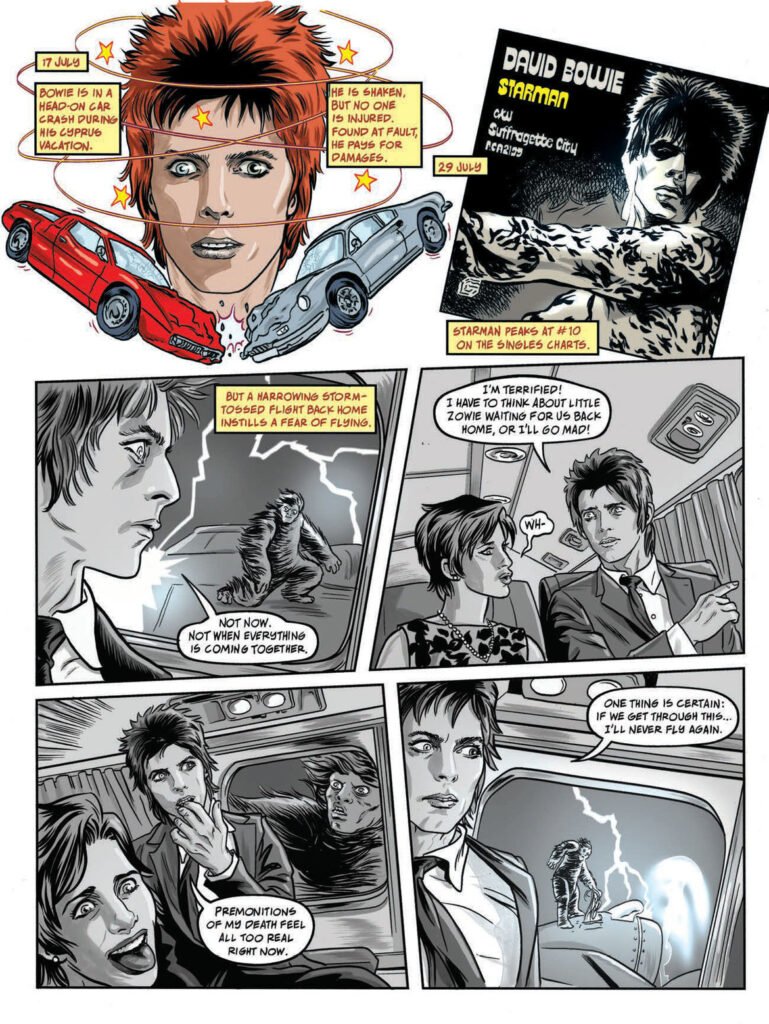

Bowie: Stardust, Rayguns and Moonage Daydreams

Michael Allred and Steve Horton – writers; Laura Allred: Artist

Insight Comics, January 2020

**

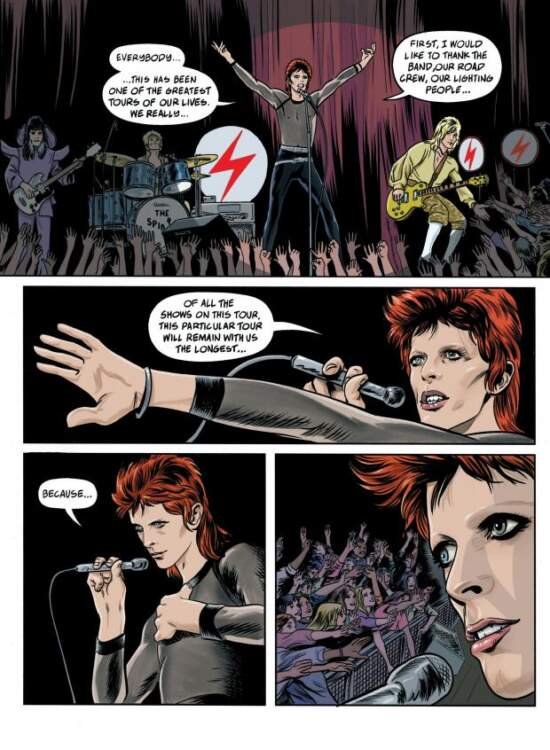

Hadden Hall: When David Made Bowie

Writer and Artist: Néjib

Self Made Hero, 2018.

Comic book biographies of musicians are extremely rare creatures. In this comparative review, we look at two comic books published within a year of each other looking at seminal moments in the life and career of musical icon David Bowie.

Mr Bowie has been a source of fascination and inspiration for millions of people. We would certainly like to read more comic biographies of musicians with fascinating lives – Mozart, Gene Simmons, Britney Spears. And these two are not the only comic book biographies of Mr Bowie – there is also David Bowie (My First Little People, Big Dreams) Board book from Maria Isabel Sanchez Vegara published on 28 April 2020, and Pat Gilbert’s Bowie: The Illustrated Story published in 2017.

Poignantly, Mr Bowie’s son, the talented film maker Duncan Jones, posted this recently on Twitter:

Mr Bowie’s sense of humour is striking, and yet perhaps the thing most people do not consider when exploring his career. Instead, they are spellbound by the theatrics, the music, and, in the case of Mike Allred’s and Steve Horton’s biography, entitled Bowie: Stardust, Rayguns and Moonage Daydreams, the savoire faire. That is an oversight.

Mr Allred in particular is an accomplished comic book creator, well-recognised in the US market, with a very long resume. Mr Allred has been involved in avant- garden projects before: our favourite is Vertical, published by Vertigo Comics, a homage of sorts to the Warhol era. Mr Allred’s co-author is Steve Horton, perhaps best known for his work for Dark Horse Comics.

This is the promotional copy for the title:

Inspired by the legendary David Bowie, BOWIE: Stardust, Rayguns, & Moonage Daydreams is the original graphic memoir of the great Ziggy Stardust!

This graphic novel chronicles the rise of Bowie’s career from obscurity to fame; and paralleled by the rise and fall of his alter ego as well as the rise and fall of Ziggy Stardust. As the Spiders from Mars slowly implode, Bowie wrestles with his Ziggy persona. The outcome of this internal conflict will change not only David Bowie, but also, the world.

Artist Laura Allred’s style is very well suited to the trippier elements of the Bowie ethos. There are jumps through time, and exchanges between manifestations of Mr Bowie throughout his career. Blurring eyes as a means of telepathic communication seem to reference Mr Bowie’s anisocoria.

Much of Ms Allred’s work involves beautiful renditions of the many celebrities which inhabited Mr Bowie’s world: Freddy Mercury, Marc Bolan, Jimi Hendrix, and Elton John. And Mr Bowie himself is brilliantly portrayed, such that you can almost see the lift of the chin and the distinctive teeth. (The portraits remind us of Brian Holland’s monster in Camelot 3000.)

In some respects these showcases of Ms Allred’s masterful portraits are a distraction from the story. We are invited to admire Ms Allred’s wonderful art, are overwhelmed. The creative team paint Mr Bowie as a tactician, a deliberate trailblazer of state and art, never wavering in his objectives or vision. And then there are the factoids: Mr Bowie attended an Elvis Presley concert but they never met (Mr Presley is the subject of a full page portrait); Barbra Streisand was interested in recording Mr Bowie’s song Life on Mars (a full page side profile of Ms Streisand’s face); the thought bubbles of contemplation that Mr Bowie had in outing himself as gay. Small pieces of information are held up to the sunlight like shards of glass, and are illuminated.

But setting aside the art, we can read almost all of this in any number of biographies. The writers sets the facts out well, but no better than any other Bowie biography other than this one is illustrated. Mr Allred is plainly an enthusiast, not, in this comic, interested in a new interpretation outside of the realm of the hallucinogenic artwork. Do not be fooled: a rigid recantation of facts underpin the trippy storytelling inherent in the art.

In comparison, we have Mr Néjib‘s Hadden Hall: When David Made Bowie, a quirkier take on Mr Bowie’s years in the lead-up to fame and success. Hadden Hall is an English translation of a French comic written by a Tunisian about an Englishman, partially told from the perspective of a personified house. Hadden Hall was a rundown place which ended up being a recording studio, a dormitory, and a private nightclub for Mr Bowie and his entourage. The hall seems quite happy with its outlandish inhabitants and their indulgent lifestyles. “When they said yes to the estate agent, a delicious shiver ran the length of my roofbeams!”

The story then mostly follows Mr Bowie’s doubts and dreams. It was clear to himself that he had talent, but how is he to execute upon it? Mr Bowie sees The Stooges live in concert and is captivated by Iggy Pop’s power vocals. He watches A Clockwork Orange and is mesmerised. There is no master tactician here with a thought-out plan to conquer the world through a combination of music and avant-garde culture. Instead there is a man who is open to influences, and yet cannot quite seem to get his act into gear. Over a beer in a local pub, he vents his frustration over the near-misses just like anyone else struggling with a career. Mr Bowie in this comic was never destined for global grandeur. He takes advice from successful musicians, like John Lennon. He is instead an Everyman, trying to work out where the rings of the ladder begin.

The two comics cannot be totally different given the subject matter. There are solid overlaps between the two comics in terms of content. The enormous impact that the motion picture A Clockwork Orange has upon Mr Bowie is unavoidable and features in both books. The rivalry with Marc Bolan receives more emphasis in Hadden Hall than in Bowie. In Bowie, Mr Bowie is a little snappy about a suggestion that he and his band, the Spiders from Mars, emulate Mr Bolan. But in Hadden Hall, it is a crossing of swords: the two most enormous egos in London find they have much in common, and as such quickly identify the other as the friendly enemy. The evolution into Ziggy Stardust is the result of a layered methodology in Bowie, but is depicted as partly hard work and a happy lottery win – a faire le buzz – in Hadden Hall.

Poignantly, Mr Néjib spends a lot of time addressing the schizophrenia of Terry Burns, Mr Bowie’s brother. It is a lonely and dark chapter. Mr Allred does not touch it. In Hadden Hall it occupies a significant part of the story. The interaction demonstrates that Mr Bowie was there for his brother, and tried: Mr Bowie houses him at Hadden Hall. Eventually, Mr Burns wants to be returned to the hospital. It is a sad moment.

The art in Hadden Hall, for verisimilitude, cannot compare to Ms Allred’s work. It is instead sketchy and highly stylised, containing many single line drawings. It is distinctly European and reminds us of Picasso, or the contemporary French art duo Differantly. It works very well as a vehicle for telling the story, and particularly, this quite amazing page:

What is our conclusion? Despite the same subject matter and the same medium, we have two vastly different approaches. The first is created by a fan who puts Mr Bowie high on Mount Olympus, where the vistas are spectacular. The second, Hadden Hall, has Mr Bowie wondering how to pay the rent, having a laugh, and desperately courting inspiration. We much prefer this second, human Bowie. As biographies go we suspect – or at least hope – it is much closer to the truth.