Writer/Artist : Hideo Azuma

Translators : Kumar Sivasubramanian & Elizabeth Tiernan

Publisher : Ponent Mon, 2005

Depression, a concept we are so used to nowadays, is that kind of feeling that leads to a complete numbness of our mental capacity. There seems to be no easy way out, in such cases, so that the end result is a mutually unintelligible exchange between a world that would like for us to live fully (either as a biological diktat, the survival of the species, and as the inhumane order issued by a society that sees enjoyment as the only meaning of a person’s existence) and an internal disorder that shuts off any possibility of even getting up from the bed and cook ourselves a nice nutritious breakfast. Yet, depression is also that kind of feeling that we might derive from reading certain books, from watching certain films, and from listening to certain songs (they don’t even need to have any kind of lyrics). We are sad because we are led to feeling so. The way to counterattack such thoughts, then, taken as external elements, is by presenting them from a different point of view, that is, by reworking their shape so as to be put under an antithetical light.

Azuma’s burnout, his wanting to leave his job and his family, or his falling into the traps of alcoholism, is rendered in such a way that we are led to take part of his experience not as uninvited guests who happen to be made privy to something they should not know about, rather as the kind of spectators who, conscious of their status, are put at the same level as the writer who has decided to tell his story. A kind of honesty, then, that is the main element of any autobiographical story revolving around such dire and dark moments of our lives, moments that can be summarized with one simple words: hopelessness. Yet, whereas hope seems a lost cause in itself, Azuma’s style as an artist and words as a writer do allow for a less depressing feeling to be derived from our turning the pages of what is, first and foremost, a confession.

The end result is a long introspective tale that manages to fend off the feeling of sadness that can only come out when too much pressure is put on the idea of an impending doom of absolute failure. We, the readers, are therefore not asked to cry along with the main character, rather to take a step back and see through his eyes, surely, but with that kind of subjective detachment (an oxymoron, perhaps) that Azuma employs in showing us not just the awful reality of life as a homeless and an alcoholic, but also the acceptance of this situation as a matter of fact. Just as he takes responsibility for his actions, so are we asked not to judge him (not too harshly, perhaps), but to read his story for what it is, something that could happen being that we, as humans, all have our own weaknesses, just as we have our strengths.

It is possible, then, to enjoy the book and realize how awful life can be, without, for this reason, having to feel the weight of a painful doom looming over our shoulders, an impending sense of failure seeping into the corners of our brain. The lack of a judgment against a world whose actions are unfathomable to us, the concept of there being no actual absolution for the actions we commit, is not and should not be taken as the result of having lost all faith in humanity and in our own power; events happen because sometimes they have a will of their own, and accepting them not as a just retribution or an unjust punishment leads to a reverberation of the anonymity of man’s life opposed to the blind stillness of the universe. We are, after all, just simple creatures who are put in a position to enjoy life for a very short duration; there’s no need to feel so sad, just enjoy the ride and don’t feel too depressed if you (or someone you know) should stumble on the way from time to time.

A chat with Kumar Sivasubramanian

WCBR : Hideo Azuma’s book is actually an autobiography, yet he decided to use a style that would be as cartoonish as possible. How would you say the end result feels like? Are the readers less invested in the story, or is the contrary true?

Kumar Sivasubramanian : This is a difficult question. Scott McCloud in Understanding Comics talked about a “masking” effect in which the more simplistically a character is rendered the easier it is for a reader to identify with that character. A character that’s drawn in more realistic detail is harder to project into because it’s clearly a different person, not yourself, McCloud argues. I’m not sure I totally agree with this. Don’t we connect with actors in movies sometimes? However, in Azuma’s case, I think it creates exactly the effect he wanted. The book is almost a list of facts about being homeless, or being a pipe fitter, or being in rehab. I don’t think he wants the readers to sympathize with him or condemn him. He just wants to depict what happened. In that respect I think the reader is totally invested, or at least I was, because the cartoon character becomes almost invisible. If it had been drawn realistically, I think we would have been distracted by his humanity, so to speak. In one of the interviews included as extras in the book he mentions that he considered depicting the story using cats instead of people. That would have been a mistake, I think. He found the right middle ground.

That said, the book is drawn in Azuma’s usual style. I don’t think he could have changed it anyway or experimented with a bunch of styles like Art Spiegelman. It’s the way he knows how to draw, and draw fast enough.

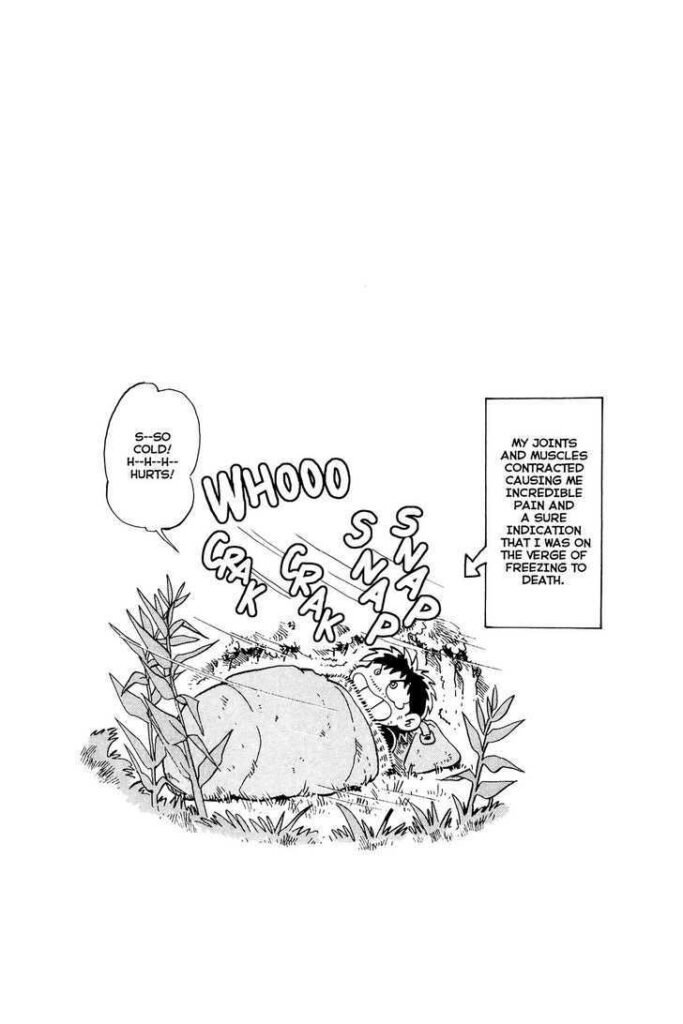

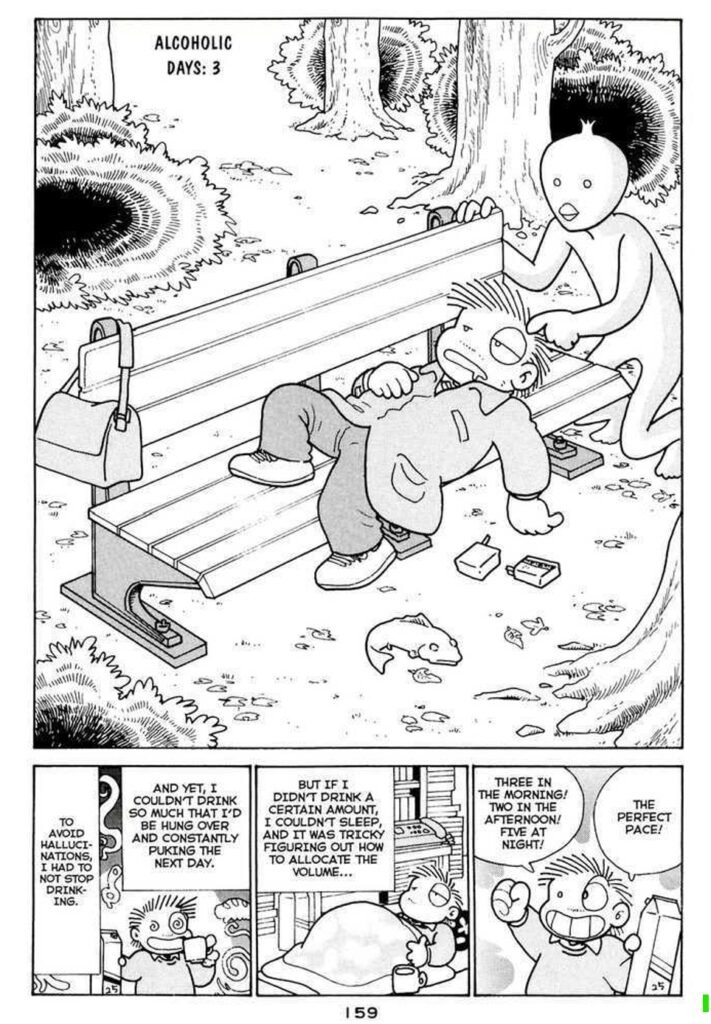

The times the art style possibly seems most out of sync is at the very start of each section: when he attempts suicide, when he’s feeling extreme anxiety, when he’s drinking so much he’s hallucinating. In those moments, you could argue the art is discordant, it’s certainly shocking to see this cutely drawn character undergoing these things, but the intention of the cute style in the first place is to draw focus away from the horror of it, and I think he succeeds in that.

Of course, every reader is different too, and it’s impossible to speak about these things in universal terms.

WCBR : The kind of people he writes about in the novel, real people, live outside Japanese society. Would you say Azuma is trying to give us a look into the lives of those who usually go unnoticed?

KS : Yes, but only to the extent that those people (homeless people, blue collar workers, alcoholics in rehab) are fresh, interesting subject matter for manga because they aren’t usually given much attention, especially in a realistic way. To me, it never feels like Azuma is trying to garner sympathy for any of those people or himself. Most of them are depicted as misfits and weirdos that he himself doesn’t understand or like. He talks in the book more than once about the pressure as a gag manga artist to not repeat a joke. With this subject matter he doesn’t have to worry about that because nobody’s covered this material before.

WCBR : The book is also a rough guide as to how a person can live on the street, without a job, a house or a family. The end result is that, after all, such a life is not unbearable. What is Azuma trying to say, here?

KS : Actually, sometimes it IS unbearable for him, and eventually he goes back to jobs and family. He only depicts a series of incidents which he thinks which will be of interest to readers, but there was months of misery which aren’t depicted. When his wife comes to collect him after his second disappearance, he doesn’t describe it, and says the scene is “abbreviated, because none of this is funny”. That plus the cute art style might have a deceptive effect, but I don’t think for a second that Azuma is encouraging anyone else to live the way he did, something which occurred as a result of his own anxiety and mental health issues. Perhaps part of the problem is that he also never shows the effects of his actions on his own loved ones, etc. I mean, he tries to kill himself in the opening pages!

WCBR : It seems as if Azuma’s problems are caused by a society that does not allow a person any kind of respite. The idea of “time out”, in Azuma’s case, is the act of leaving society (his job, his wife, his status) for good. Is Azuma accusing society (and, theoretically, his readers) as to how a mangaka is treated, a unit who simply has to produce new material everyday?

KS : No, I disagree with this. Yes, we know mangaka are put under ridiculous pressures to produce content. But Azuma only ever points to his own mental health issues and his own inability to deal with the pressures of being a mangaka (at one stage drawing 130 pages a month!). There must be more stories like Azuma’s about mangaka having breakdowns, and those stories aren’t being told, but even so, Azuma never says, “The industry is toxic for all mangaka” – he only ever depicts it as his own failing. Also, even though he exits society, he willingly REENTERS society and gets a blue collar job, and even starts drawing comics for an industry magazine!

WCBR : Might we say that one of the goals of this book is to humanize artists? Full of flaws, unable to work properly, in search of a better life and suffering from tremendous illness such as depression, burnout and alcoholism.

KS : You could read it that way, but I think Azuma’s intention is just for his readers to enjoy some interesting incidents and gags. And again, we only see ONE artist – Azuma himself. He never introduces us to his mangaka friends who are going through similar breakdowns. I feel like he’s trying to avoid making statements. If anything, if you look beyond the incidents and art style and think about what must have really happened, he becomes a character that’s somewhat difficult to sympathize with – his utter lack of thought for his family, his stealing from another homeless man, etc.

You can’t help but wonder about all these things though. I translated this book 15 years ago, but I still think about it all the time. I can’t say that about many of the other books I’ve translated.