Creator: Oliver Bly

Mad Cave Studios, 2024

This title, part-charming, part-hallucinogenic, was published by Florida-based Mad Cave Studios in 2024. It is written and illustrated by Oliver Bly, who resides in Washington State in the US. The Mushroom Knight won the Russ Manning Promising Newcomer Award at the 2024 Eisner Awards along with the Next Generation Indie Book Award for Best Graphic Novel. We should have reviewed it two years ago: we are late to the party.

Here is Mad Cave Studio’s promotional copy:

An adolescent girl searches the deep dark woods for her missing dog, entangling her destiny with a chivalrous mushroom faerie on a mystical quest to protect the biome from catastrophic ruin.

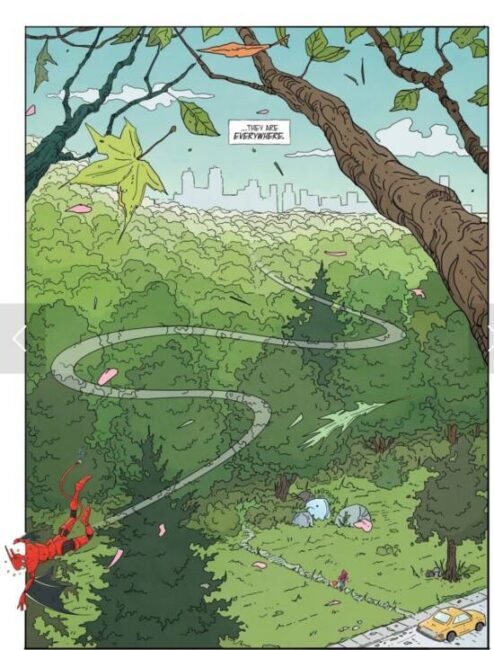

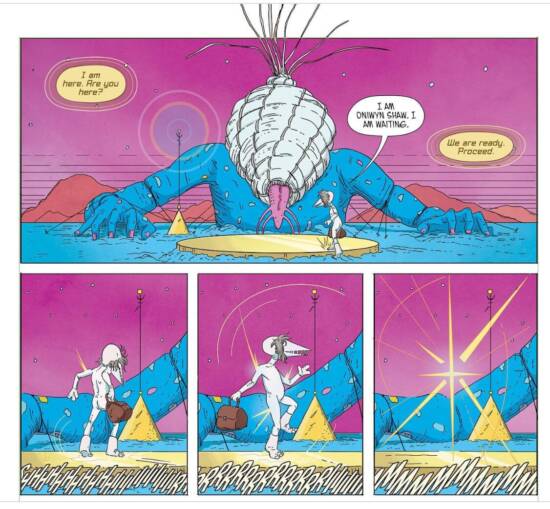

The Mushroom Knight follows the adventures of Gowlitrot the Gardener, a sentient bipedal fungus created by a race of woodland gnomes called Gödels, as he investigates and unearths a deadly conspiracy that reveals the true nature of himself and the devastation humans have wrought upon the global biosystem that he has sworn to protect.

Mr Bly has crafted an enchanting muddle of Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Knight’s Tale, Alice in Wonderland, and a lecture on an introduction to semi-urban biomes. It is a fairy tale, of sorts, but overlaid with a very dark mystery – a suicide, a murder, and grim forces slowly intruding on a small and peaceful world sitting just outside of our eyesight. Our perception of Mr Bly’s world coincides with main protagonist Gowlitrot the Gardner’s understanding of the menace he confronts: “There’s something fiendish out there, Hops, just beyond my line of sight. I can’t reckon it, I can’t make the pieces fit.”

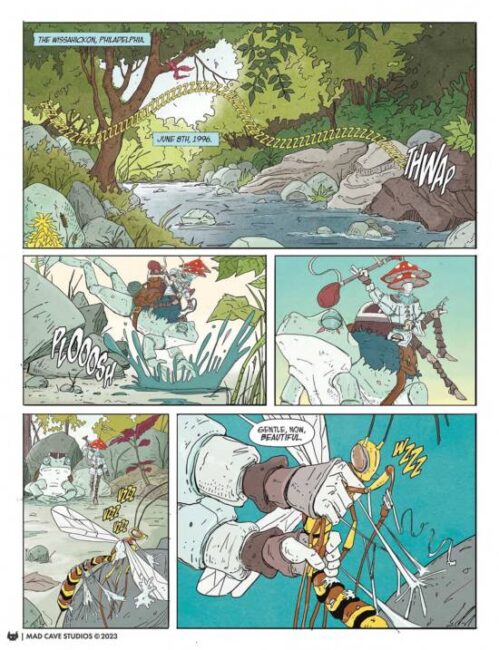

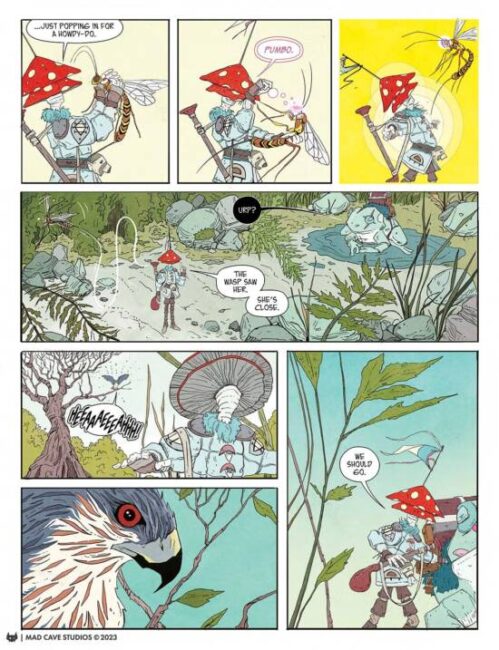

Gowlitrot the Gardener is a mushroom in the shape of a man with a pennant-equipped, spotted helmet, who rides a frog named Hopalong. His immediate task is to retrieve a magical artifact called the Candle Fly. Gowlitrot is a formidable magician. In addition to being able to talk to his frog and to squirrels (“disgusting creatures”), he can “pop… in for a howdy-do” (probe the memories of insects), zap the brain of an attacking bird of prey, borrow the soul of a human’s leg (a new one by us – body parts have their own separate souls?) to repair his own eviscerated one, and, perhaps, the existentially dangerous Essicrissical Flight. Which, we think, is the ability to travel between Gowlitrot’s realm and ours, but the mystification of the text does not make that immediately clear.

Our use of the word “mystification” is very deliberate but is no criticism. The language of the characters living in Gowlitrot’s world is arcane, hard to follow, and flowery as a calligrapher’s script. It is this use of fluorescent and archaic language which reminds of us Chaucer. The various protagonists do not speak in Middle English but we nonetheless think Mr Bly deliberately draws upon Canterbury Tales: Mr Chaucer wrote in his introduction:

“Whan that Aprille with his shoures soote,

The droghte of March hath perced to the roote,

And bathed every veyne in swich licóur

Of which vertú engendred is the flour.“

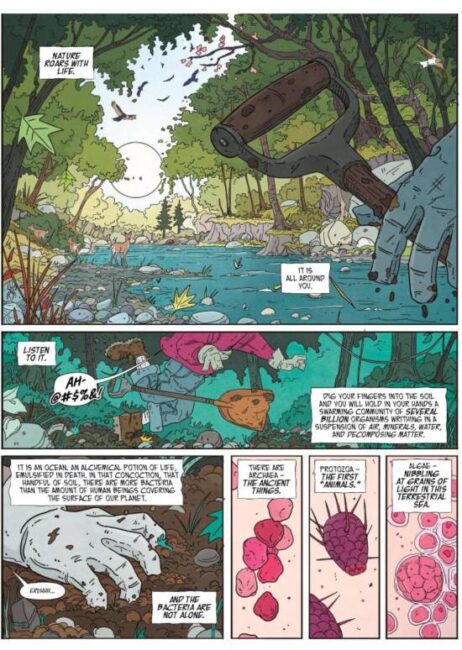

And Mr Bly writes:

“Every actor in this active pageant, from the amoebas in the water to the sycamore trees drenching their roots from up above, have learned their lines over eons of push and pull, each one in accordance to the other.”

We think The Mushroom Knight is a North American Canterbury Tales.

But further, it is very text heavy. Enormous amounts of floral dialogue are barely contained by word balloons and panel gutters. That will not suit some readers, but for those who recognise that they are on a syntactic adventure as much as a fantastical, micro-ecological one, the complex and dense prose will delight.

What is Gowlitrot’s small realm? It is Medieval Europe wrought little: it has village industries, is subject to ecclesiastical laws, it has a centralised authoritarian government with fuzzy control on the fringes, and it is subject sovereign dangers (“Could be stinky, tricky Troll business,” says a sinister Knight,, conducting his own parallel investigation of events. “Much worry in the West. Did you know? Rumours… Peppinji is back from the dead.”). It could be Surrey in the 1400s. “The entire world is a joke writ by clowns for the amusement of devils,” says a despairing barkeep late in the volume, channelling Chaucer’s The Pardoner. This world is both familiar and strange, just like the Middle Ages of Western Europe.

It is also by happenstance a woodland in Philadelphia in 1996, and with that exploration of the North American ecology comes the wonderful prosaic explanation of the interaction between various aspects of nature some of which we have quoted above. (Our tip is to read it out-loud for full poetic effect.) Robert Frost said, “We tend to forget that civilization is nothing more than a clearing in the woods.” But here, the civilisation is the woods.

Gowlitrot takes the soul of the leg of Lemuelle, an elementary-school human girl on a mission to find her lost dog, named Beans. They communicate briefly in this volume, thanks to the Candle Fly altering Lemuelle’s understanding of reality and leading her to stomp around and sing a song not far removed from The Beatles’ “I am the Walrus”. Gowlitrot promises to repay her thrice-fold what the loan of her leg’s soul has cost her. And it costs her a lot: her leg is numb and occasionally in pain, she becomes depressed and disinterested in class and drops out of her school talent show, and she softly mourns her lost dog. Fast forward in time at the end of the volume, and Lemuelle is an adult undergoing therapy and who seems to have forgotten something important from her past. We suspect Gowlitrot’s intervention in her memory.

Some of the story is grim. The Knight kills a captured pet cat with his crossbow, in cold blood, and in front of Gowlitrot’s fellow Gardeners, who seem incapable of doing anything about the murder. Erdagaude’s death is miserable. Lemuelle’s despair, quiet in her bed, is hopeless and sad.

All of this is rendered in fine line drawing, the realism deployed so as to catch the anatomy of, say, the Regal Moth and the Hickory Horned Devil caterpillar in the ecological meander forming the introduction, but also the strangeness of the Chieftain’s eldritch interaction with the captured blue giant Muuvae Bu’bacca. The champion artistic element of the title however are the colours, for which Mr Bly teams up with Steph Snow. The colour palette is appropriately psychedelic at times, wonderfully naturalistic when depicting the forest floor, constantly stimulating, and as the story progresses, it seems to us that it becomes more outlandish.

But otherwise… a sentient magical mushroom? Who rides a frog, like an errant knight? The obvious question is whether something mycological got into Mr Bly’s system which has served as creative inspiration. Some of the story and the art is very trippy indeed. But Mr Bly explains his interest in mushrooms in this interview with The Comic Book Yeti’s Cryptid Creative Corner (Oliver Bly talks The Mushroom Knight | The Comic Book Yeti Cryptid Creator Corner podcast), describing the experience of finding a fungi in a forest, in a way that is as charming as the title itself:

I guess, you know, I’ve been a outdoorsy person since I was a kid. And by that, I mean just someone that goes outside and would play in the woods. And like to be outdoors. And I think the love of mushrooms or just the interest or fascination in them comes from just going on walks in the woods when you’re strolling and sort of just observing your eyes will sort of comb across the ground. And every once in a while, there’s just this object there that is quite unlike all the other objects in the woods or the other plants. And I guess mushroom foraging or hunting kind of came out of that. Additional fun you can have when you’re going through a walk and you start paying attention and looking for mushrooms.

You know, you kind of enter into a meditative state when your eyes are kind of combing around and brushing through bushes across tree bark. And then there’s these little almost like art installations and mushrooms are so vibrant. They can be in so many interesting colors.

They come in so many different shapes. And they all have their own kind of personalities. And so and they’re also kind of easy to overlook if you’re just kind of trotting along and not really paying close attention.

So if you start looking for mushrooms, you know, you kind of enter into a meditative state and you’re really paying close attention. So if you go through and you want to go out and do a hike because hiking is lovely and it’s nice to get out and experience the natural world, looking for mushrooms kind of becomes something to do while you’re doing that. And it’s kind of like this entryway into getting kind of a meditative state of peacefully just observing and looking and watching.

And then all of a sudden underneath something there’s this bright little pop of orange and it might only be, you know, maybe a quarter of an inch in size or it could be large and on the bark of a rotting tree.

So the roundabout way of answering your question, I guess, I got into mushrooms when I was younger and then probably again as an adult, I got more into understanding what their names were, what the stories were. And just being fascinated with mycology in general because it’s such a diverse kingdom of life.

Two more volumes of this remarkably creative, highly engaging story have been released since 2024, and we will review each of these later in the year. Mr Bly’s website’s page dedicated to The Mushroom Knight is located here: THE MUSHROOM KNIGHT — OLIVER BLY .