The Arrival

Lothian Books / Hodder Children’s Books, 2006

Writer: Shaun Tan

Shaun Tan is an Australian comic book creator based in the same slightly obscure city as your reviewer, although we have never met or dealt with him in any capacity. Mr Tan however has a formidable reputation, although not within the traditional comic book industries. In 2011, Mr Tan won an Academy Award for a short animated motion picture called The Lost Thing. Otherwise, in 2006, the graphic novel we are considering in this critique, The Arrival ,won the Book of the Year prize the New South Wales Premier’s Literary Awards. The Arrival otherwise won the Children’s Book Council of AustraliaPicture Book of the Year award in 2007 and the Western Australian Premier’s Book Awards Premier’s Prize in 2006.

We are therefore very late to the party. But Mr Tan has two works due for publication this year, one entitled Cicada due for publication in June, and another called Tales from the Inner City due for publication in September. So perhaps this is not so much a tardy review of a twelve year old comic as an introduction, to our very dispersed international audience, in respect of an acclaimed creator whose forthcoming works we will be discussing again this year.

The Arrival presents difficulties for us. It is entirely devoid of any dialogue whatsoever. The ethos of World Comic Book Review’s critiques is to avoid commentary on art because, first, we are not competent to critique art, and second, art is very subjective. Tastes can differ and we have no desire to argue over personal aesthetic preferences.

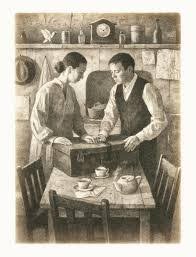

Nonetheless, the art in this comic is remarkable. It is strange and beautiful, primary in either monochrome or sepia tones so as to suggests stories within the story. These vignettes are flashbacks told by characters who the primary character (who for want of another name we shall call “the Father”) encounters as he explores his new home.

The Father is very reliant on the kindness of strangers to help him understand directions and maps. It seems many of the residents who assist him have left their homes to come to the city to escape their respective points of origin. These are told to the Father in haunting ways. One elderly man working in a factory has a history, where marched in a patriotic column of troops from his pretty village towards war, stumbled through mud and then skeletons, and then returned on crutches and missing a leg, the sole survivor of his fellow soldiers, to find his village in ruins. The man must look away as he concludes his story.

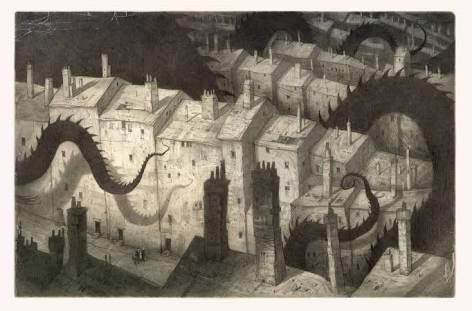

Other vignettes are even more haunting. One of these, told by a friendly bearded man who invites the Father to join him for a meal, pictures the desperate escape by the man and his wife from a horde of giants, each dressed in what looks like helmeted asbestos suits, wielding terrifying vacuum cleaners which suck up helpless people and expel flames from a backpack mounted exhaust. This is plainly an allegory for a genocide. The man telling the story looks European, but it is (we suspect intentionally) difficult to pin down a particular ethnicity or event associated with this, or indeed any of the silent tales describing the refugees’ trigger for escape to the city. The Father himself has left behind his wife and child in a place haunted by the shadow of an ominous, enormous black dragon (a reference to China?).

There are several failed efforts at trying to secure employment including as an advertising sign poster, a job he is fired from because of his inability to read the local language. The Father repeatedly posts his signs upside down – both a funny and slightly sad moment. Eventually the Father gets a boring job in a large factory. But it is safe and it pays. Eventually he gathers sufficient money to send to his wife and daughter, so as to enable them to join him in his new home.

The strangeness of the subject matter of the photorealistic art is quite intentional. The reader is intended to be projected into the same alien environment that a refugee encounters upon arrival in a strange land. The animals are very different, the language is incomprehensible, the clothes are odd, and the food looks ghastly.

The text itself has a cover that looks very much like an old and battered leather photo album. Inside are many sepia-toned illustrations of people – head shots, the sort of photographs which would be taken by immigration officials. Each face has a different message. And the comic itself consists of many hundreds of drawings, some small and some double paged, each contributing in either direct or oblique ways to the unwritten message of the text.

Years pass and the family adapt to their new surroundings. And in time, we witness the Father’s daughter being approached by a newcomer seeking directions, and the daughter is very happy to help. As the Father was assisted by refugees who adapted to their new lives, the Father’s daughter has without thought taken on the mantle. Mr Tan forms a view on a culture where the desperate are accepted, and where helping strangers is a happy obligation which is passed on and repaid. It is a stirring message. But the culture of this fictional land contrasts with the disturbing spiral of non-acceptance of genuine refugees by some Western governments (including Australia, Mr Tan’s home country. Mr Tan himself is of Chinese Malay descent).

Mr Tan makes his point in a subtle way: We could do much, much better to welcome newcomers and understand why they have come at all.

The Arrival is a beautifully rendered insight into the life of a refugee sitting into his new home. Mr Tan’s website is Shauntan.Net We are looking forward to his creative output in 2018.