Creator: Tim Gauld

Drawn and Quarterly Press, 2012, 2023

On a very recent trip to London, your reviewer found this title, Goliath by Tim Gauld, at the wonderful Gosh! Comic shop in Soho. It was sitting on a table with a variety of comics from independent publishers. Goliath is published by Drawn and Quarterly Press, who in our experience rarely miss a beat.

The story is Mr Gauld’s Kafka-esque take on the famous biblical story from the Book of Samuel, in which the future king of Jerusalem, David, as a boy uses a slingshot to kill the enormous champion of the Philistines, named Goliath of Gath. Goliath in this story, however, is actually “in admin” in the army of the Philistines. He just happens to be unnaturally tall. Someone in the leadership of the army decides that it would be efficient to have a trial by single combat between a warrior of the Philistines and a warrior of their adversaries, the people of Israel and Judah.

Rather than choose the best warrior, they choose the tallest. Goliath himself notes to the Captain, who is Goliath’s coach and management in the fight, “I’m not a champion! I’m the fifth worst swordsman in my platoon!” But the endeavour seems to be based on a bluff. “You’re missing the point, Goliath. You look like a champion. All you need to do is act like a champion and the enemy will cower before us. There won’t be any actual fighting. This is a battle of minds.” Too bad, then, that when first asked to read out loud the words of the challenge, Goliath passes out in horror and what he is supposed to do.

Like all good parodies, Goliath strikes the mark because of its serrated truths. When they first meet, the Captain makes Goliath wait outside his tent in a wait that takes up an entire page of six panels: it seems that for millennia, an indicia of casual and oblivious authority is to expect other people answer your summons and then sit about to wait for you. The Captain himself is the exemplar of the parody. He not a bad guy but seems consumed by his ambition: the half-baked escapade is clearly his brilliant idea. “I’m worried. It’s been forty days: the King wants results. I’m worried he might pull the plug.” Later, he apologises for getting worked up over the prospect that the King might shut down the project. “Sorry I shouted. Not very professional. I’ll go and find the boy. But really got for it today, ok?”

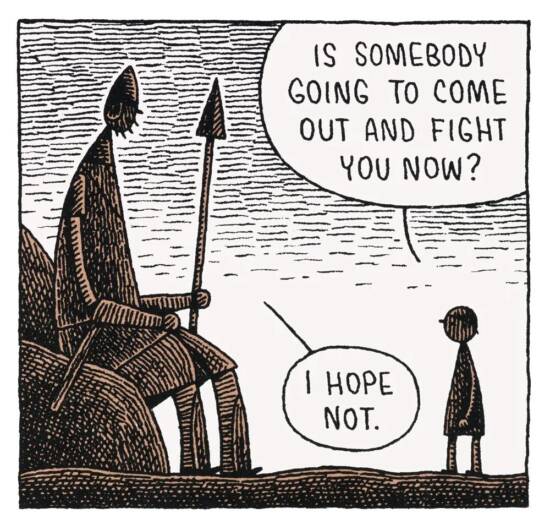

But… go for what? Isn’t Goliath doing his job well by reading his script and being so intimidating by his height so as not to procure a challenger? Is the Captain feeding the King of the Philistines a battle strategy which is different to that which he is telling Goliath? More specifically, has the Captain not told the King that Goliath is a pacifist and a poor excuse for a fighter?

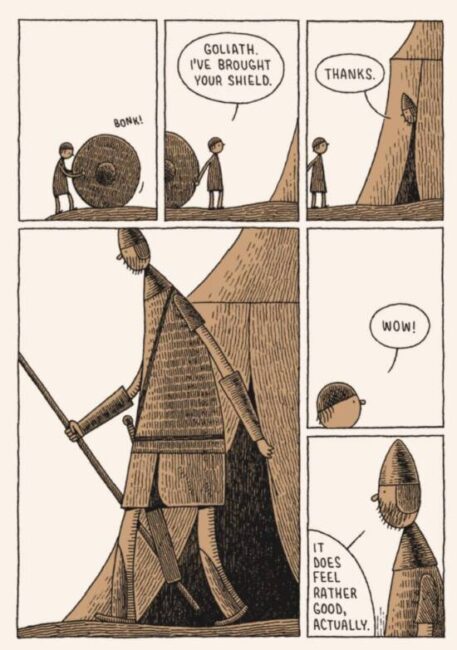

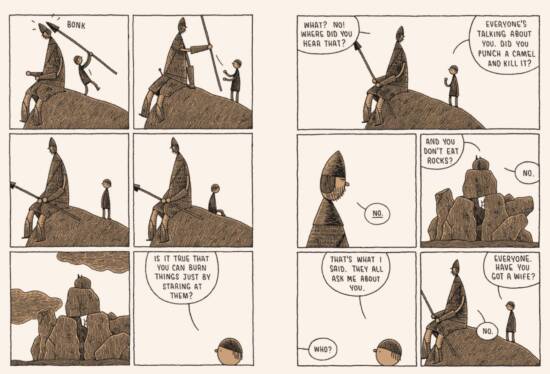

The parody is accentuated by Mr Gauld’s very simple artistic style and colour palette. There is no glorious purpose in a landscape of tan and brown, with limited depth in the landscape attributable only to Mr Gauld’s cross-hatching. The economy of line-drawing extends to the depiction of the characters. Goliath is narrow-shoulder, thin-haired, and his face is adorned with a scrappy beard. His thin arms and plug nose do not suggest even vaguely that he is a hero. The Captain wears a helmet with a scraggly plume. David, when he appears, is dressed in neat stripes of rags.

Little indicia tell us things about the Philistines’ culture. Goliath’s brass armour is slowly falling to pieces, suggesting shoddy craftsmanship, and there is no urge by anyone to fix it. Entertainment in the King’s encampment consists of the cruelty of animal baiting: dogs against lions, and bears against leopards (offensive to only contemporary sensibilities, given bear baiting was common enough in the United Kingdom until 1835). One of Goliath’s colleagues offers to set up a fight between Goliath and the chained bear for a 50/50 split and the promise of intervention if things go out of control: Goliath, who is not a man of violence, politely refuses. Goliath goes to his plot of desert every day to read his script, and is accompanied only by a boy (his “shield bearer”, who is so small that he has to roll the shield) and has no other logistical support at all. In the meantime, back in the encampment, rumours spread about Goliath’s prowess – he can burn things with his eyes, eats rocks for breakfast, and can kill a camel with one punch. No one is actually on the ground to assess and support Goliath. Goliath’s people are waiting for him to deliver victory resulting in the enslavement of the people of Israel and Judah, apparently oblivious to reality.

At one point we wonder if Goliath might escape his destiny. After all, the reworking of history by Mr Gauld might lead the Captain being mistaken for Goliath, or other quirky twist. Goliath and the shield-bearer spot the chained bear running away into the desert and make no effort to stop it. The bear is a metaphor for Goliath. Goliath’s sudden celebrity is a cause for entertainment just as the bear’s success in the pit was. The bear’s chains are akin to Goliath’s orders, and Goliath confides in the boy that he is half-planning to disobey the Captain and run away. What if Goliath, like the bear, can make it out?

Sadly, it is not to be. Victors write histories, as we know, and so the recantation of the story of Goliath’s defeat are played out in the literally Biblical terms which we see in the Old Testament: David crushes Goliath’s skull with a stone from his slingshot, then decapitates Goliath, while the Philistines (or rather, just the boy shield-bearer) run away in terror. David seems just as surprised as anyone, and taking Goliath’s head as a trophy seems more like shoplifting than a final humiliation upon the Kingdom of the Philistines. David’s victory takes place in a quiet patch of desert with some rubble and a twig which the Captain identifies as a bush, described in 1 Samuel 17 as the Valley of Elah. There are no battle lines, is nothing glorious about the “fight”. A nice guy has died because of a stupid plan, and now his people will be enslaved.

Goliath does receive a moment of peace before his murder. “I’m starting to quite like it out here… its sort of beautiful, isn’t it?” Goliath can see peace in the desolation. We as readers could take solace from Goliath’s contemplation of silence in the last hours of his life. But instead, Mr Gauld causes us to be contemptuous of the bureaucracy which has led to the death of a gentle, contemplative soul with a quiet sense of humour, and we sneer at the revisionist history of a conquering power which casts the hapless administrator as the loser in an epic battle against the plucky David. This is masterful story telling.

Here is a link to Mr Gould’s website: Comic Books — tomgauld.com