Writer : Antonio Altarriba

Art : Keko

Publisher : Norma Editorial – 2014 (Spanish edition)

“Matar es un arte”, that is, killing is an art. What kind of art it is may lead the reader down a path that is better left sleeping. Yet, as curiosity is what makes man discover new inventions, so is it that we find ourselves unable to stop reading Altarriba and Keko’s graphic novel about a university professor who happens to be a killer. Death is not simply a goal he tries to achieve; it seems more of a natural part of his life that needs t be performed (the killing, that is) about two or three times a years, as if we were being presented the story of a modern day believer who needs to perform a ritual sacrifice to appease the gods. Yet, such gods do not exist.

At first we might be led to believe that the meaning of the short novel (about 130 pages) lies in the fact that killing is something only people with serious mental problems can carry out. It wouldn’t be, perhaps, too far from the truth: our main protagonist is detached from its community, creating a strong dichotomy between what we perceive as social life and the consequences of our antagonist’s misanthropy. There don’t seem to be many activities he enjoys: his relationship with his wife is non-existent, his affairs with other women don’t seem to give him enough joy, and his job as a university teacher looks more like a chore. There is no chaos in his life, yet while this might mean that everything is perfect, the reality is that what we are being presented with is a world of complete and utter barrenness (in fact, he cannot have children, due to his choosing to have a vasectomy).

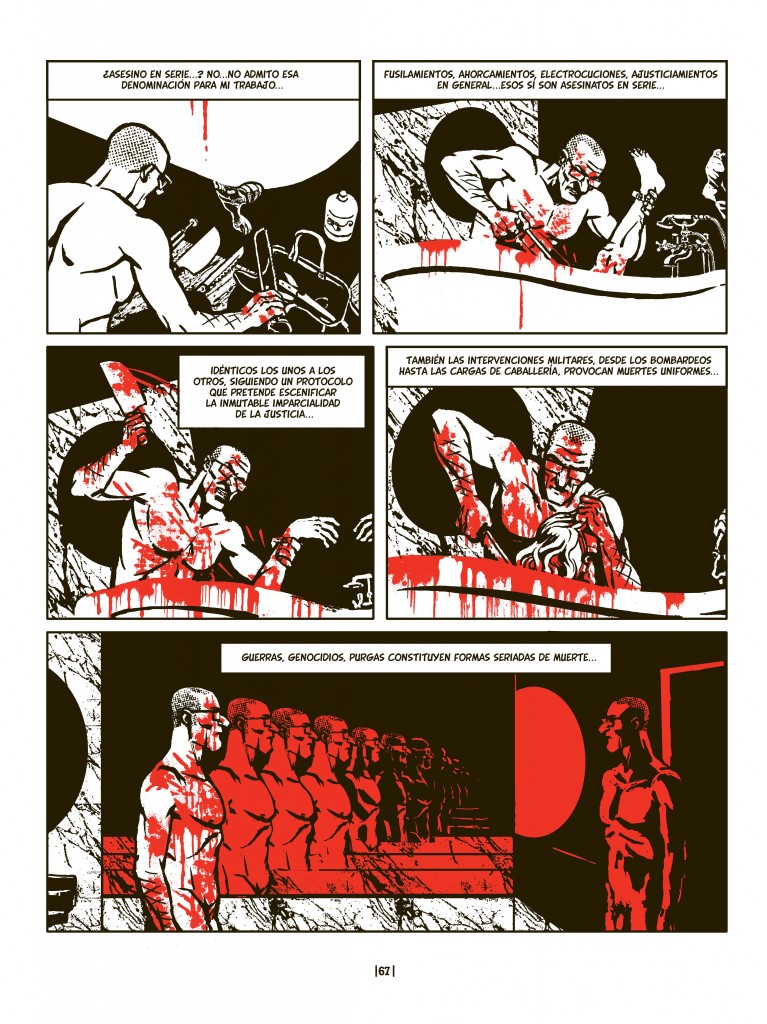

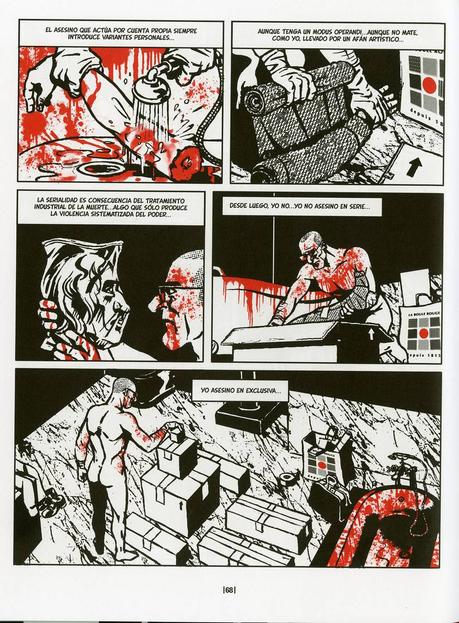

Yet, the novel works on many levels and depicts a society that has little to be happy about. The killing that Enrique performs so meticulously is the only way he seems to feel anything, that is, a feeling that has little to do with what comes from the heart, and more to do with what comes from the mind. Such killings, he ponders, are nothing compared to what the world has seen during the last century. In a way that reminds us of Chaplin’s bleak Verdoux, our university professor cannot but stress how taking someone’s life is part and parcel of who we are as human beings, and that, oddly enough, a person who kills hundreds, thousands and millions is seen as a different creature than those who kill a dozen or two, hiding in the shadow so that the police cannot catch them.

Death, so thinks Altarriba’s professor, is also something that is inherently Spanish. Our protagonist and a few of his friends are seen quarrelling with their colleagues over how ETA (and its members) should be seen in light of the past (the bombings), the present (the prisoners) and the future (a possible independence for Euskal Herria?). There is an unresolved dialogue between those who think a united Spain should be preserved and those who unflinchingly believe that the Spanish peninsula should see more political diversity in terms of borders; such dialogue is tainted by the element of terror, and how, depending of the point of view of those who talk, we are faced with terrorism or heroism. What are we to do, so seems Atarriba to be asking us, in such situations? After all, don’t we root for Enrique and yet, at the same time, find his killings odious once we start thinking about his actions?

Perhaps the problem is having a clear mind. The disgusting world Enrique lives in is not reason enough to forgive him. The shallowness of the surrounding elements and the absurdity of the social constructions are not such that taking another man’s or woman’s life should be considered a minor blemish. There is a deep misunderstanding in Enrique’s mind as to what art actually is or, better said, his fixation on violence and death being represented in art veers more towards a biased point of view than an actual reality of what those works of art really are. Altarriba and Keko, in fact, seem to show us a world that is closed in on itself, a place where no forces can play so that no centrifugal nor centripetal actions can take place. All is still and, being that we – as animals – need to move, this leads Enrique towards what he considers a logical conclusion: killing as an art.