Wolverton, Thief of Impossible Objects

Burnt Biscuit Books, 2017-2018

Writers: Michael Stark and Terrell T. Gerrett

This charming comic book, the subject of a fully-funded Kickstarter campaign, is concerned with a thief who goes by the sobriquet “The Black Cat”. His real name is Jack Wolverton, a thief and adventurer who “specialises in the arcane, the accursed, and the occult.” Interestingly, the story is set in 1910. Often overshadowed by the Great War, this fin de siècle age was the subject of enormous change. Electricity replaced gas (noted by the writers, Michael Stark and Terrell T Gerrett), automobiles replaced horses, and the industrial revolution was in full swing. Globally, the English and the French signed the Entente Cordial, formally concluding centuries of conflict, Kaiser Wilhelm was modernising Germany, Japan had crushed Russia at sea in the Russo-Japanese War, and the United States had inherited the problem of Cuba as a sour surprise from the result of the Spanish-American War. Messrs Stark and Gerrett explore a fascinating era, untouched by comic books to date.

The vehicle for that exploration, Wolverton, is plainly a homage to the 1930s-1950s Australian actor Errol Flynn. Wolverton has Flynn’s flair, his womanising ways (having a hand chopped off would interfere in his removal of corsets, Wolverton quips), a Zorro-seque mask, and even Flynn’s pencil moustache. Only the épée is missing. Wolverton relies upon stealth, wit, and cunning, wise-cracking all the while.

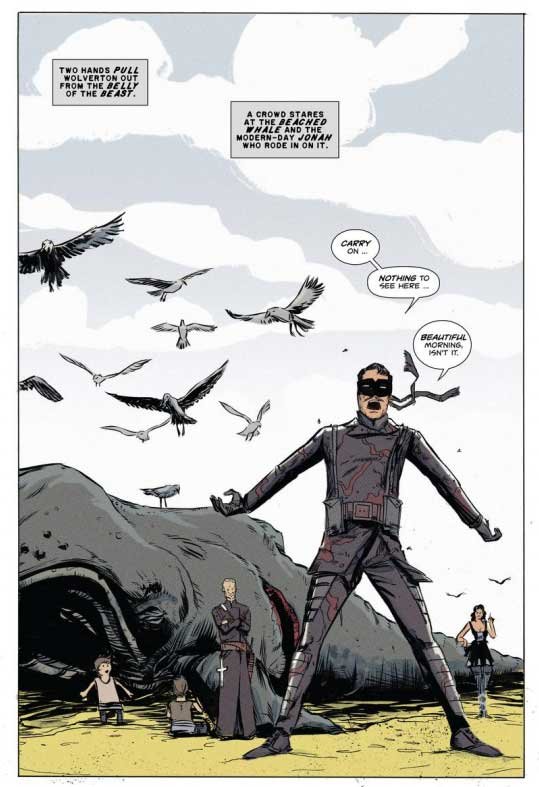

Quips abound. The opening page features what appears to be the text of a note from Wolverton to a victim of theft: “Terribly sorry, but you have just been robbed by the Black Cat! If it’s any consolation, I feel absolutely rotten about it. I’m so conflicted, I might have to cancel tonight’s dinner reservations… Again, awfully sorry about this.” On board a freighter in a storm, stalked by a magically-animated statue with six arms, Wolverton mutters, “Always with the running and the chasing!” The humorous content is articulated by other characters: the ship’s turbaned captain, unexpectedly wielding sorcery, yells at his crew as he wrestles with the helm in a raging storm, “First man who vomits gets docked a week’s pay!”

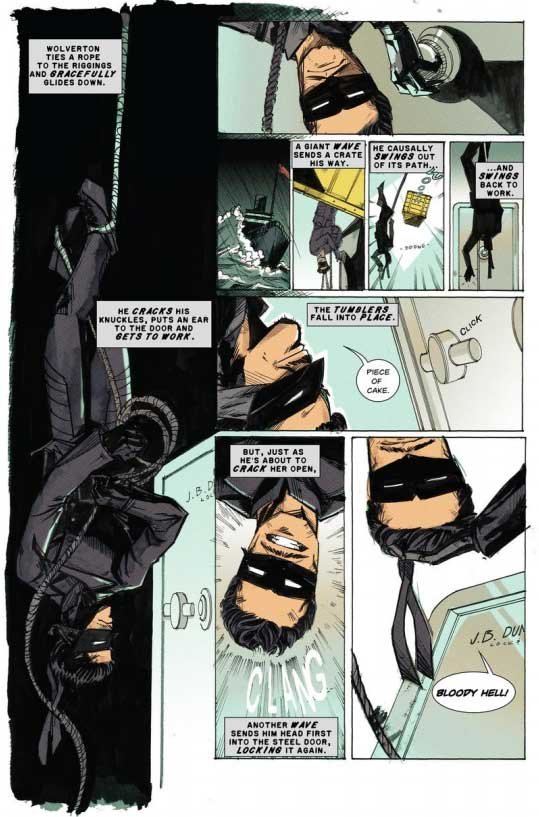

The construction of the story is notable in two respects. First, it eschews dialogue in favour of narrative text boxes. This boxed narrative carries its own amused voice. Such very heavy use of narrative boxes is out of fashion. Contemporary story telling in comic books tends to rely upon the dialogue propelling the plot. But here it works very well: the text sounds like a quirky 1910s voice, languid, Wildean and amused. Some of this is very funny indeed. Suspended upside-down within the freighter’s cargo hold, Wolverton cracks a safe with ease. But when a wave strikes the ship, his head clangs on the safe door, causing it to shut and kick. Wolverton needs to start again. It’s dry slapstick, a rarely seen category of humour which requires technical skill.

Otherwise, the heavy use of narrative text causes the story to read like a 1930s pulp tale rather than a 2017 comic. The technique cleverly dates the comic.

The second element arising out of the construction of the story is the juxtaposition between the adventure-filled hijinks of the first half of the story, and the ominous back end. Messrs Stark and Gerrett have borrowed the dire title character from Oscar Wilde’s only novel, “The Picture of Dorian Gray.” Here, Lord Gray serves as the villain. Within this comic, Dorian Gray’s reputation is well-known: he is a warmonger, the target of assassination, and is burned in effigy. Night follows day: Dorian Gray’s appearance follows that of the sunny Wolverton. And instead of one magical portrait preserving both his appearance and his health, as seen in Mr Wilde’s novel, here Dorian Gray has many.

Both Wolverton and Gray covert the same thing: the Hope Diamond. In this story, the Hope Diamond is not just the world’s largest diamond but has “been cursed by every god in the Hindi pantheon!” It is an object of powerful magic.

The concluding page contains compelling narrative and a monologue from Gray: “We pull back to reveal a well-appointed room filled with priceless antiques. As well as a shocking collection of oddities and grotesqueries. And, there’s always room for one more.” The monologue takes over, as Dorian Gray addresses a blood-soaked portrait of himself. “You know how I feel about mixing with the hoi pilloi. Why don’t we schedule a far more private viewing of the Hope Diamond, then?” Gray is silhouetted by fire. Blood and flame renders the character a demonic figure.

This is a clever, amusing, well-devised comic book.