Writer: Scott Snyder

Artist: Dan Panosian

Dark Horse Books, 2024

Western comics, to a non-American audience, might seem unexpectedly resilient. But the themes out of the Old West seem to be nestled in the American psyche. And Western horror is such a particularly American theme. Your reviewer first encountered Western horror in Vertigo Comics’ Jonah Hex: Riders of the Worm and Such (1996), but “Weird Western” has a long pedigree at DC Comics. (It would be interesting to know the point of conception of the genre. Wikipedia does not have much to say: Horror Western – Wikipedia . Perhaps it has long roots twined out of Louisiana’s American Gothic, explored – literally – in the as-yet unfinished Manifest Destiny – see Manifest Destiny Volume 6 (review): Fortis and Invisibilia – World Comic Book Review.)

In any event, here is Dark Horse Books’ promotional copy for this title, Canary:

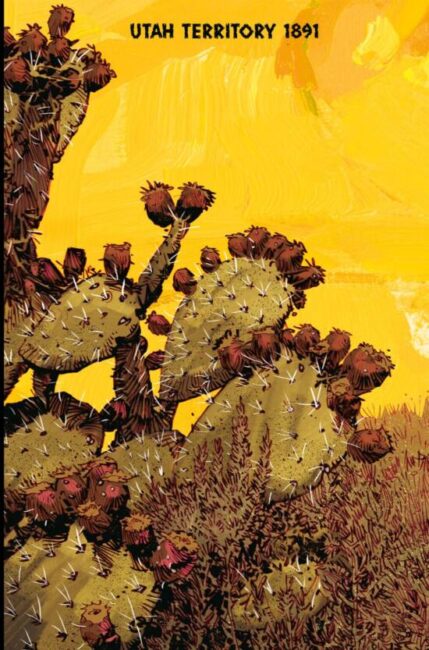

In 1891 a mine collapsed into itself. What was the dark substance found 666 feet underground? Blending modern horror, historical fact and Western lore, Scott Snyder and Dan Panosian have created a uniquely terrifying thriller with Canary.

During the final days of the Gold Rush, one mining company in Colorado, pulled up radioactive Uranium, and then the mine then collapsed in on itself. Legends sprung up about the mine being cursed or even haunted. Now the Frontier is closed, the gold and silver mines have dried up. The country is becoming “civilized,” and yet, in one stretch of the Rocky Mountains, a terrifying, new kind of violence is suddenly emerging. Random killings. People going mad and murdering neighbors, classmates without real cause. When a schoolboy kills his teacher with a hatchet, a famous federal marshal named Azrael William Holt is called in to investigate the killings. What he–and a brilliant young geologist–uncover is stranger and more horrifying than anything they could have ever imagined.

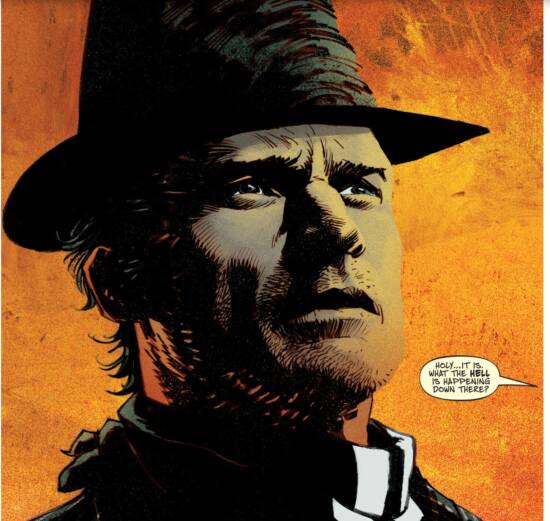

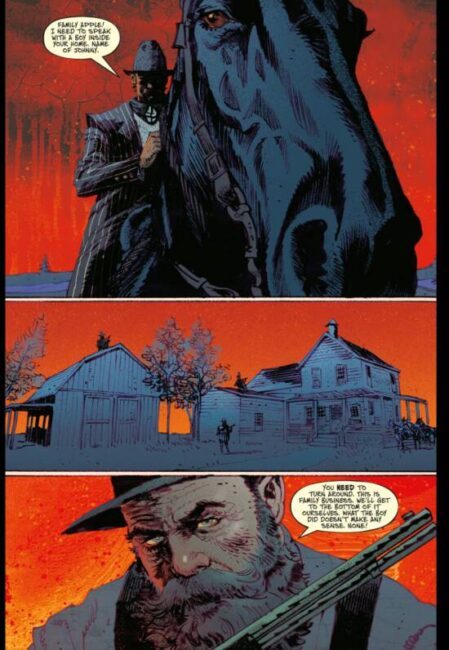

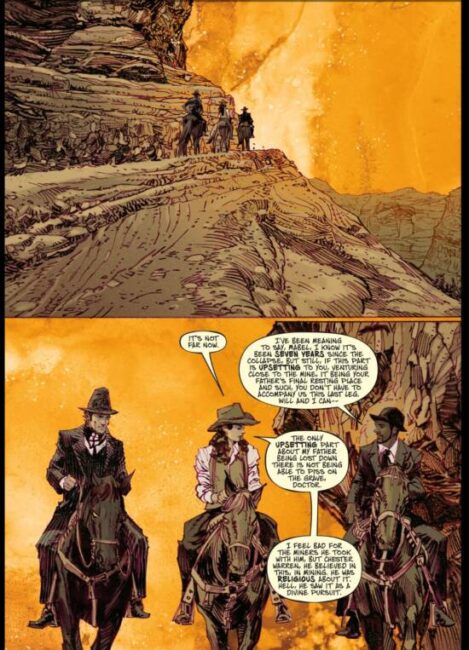

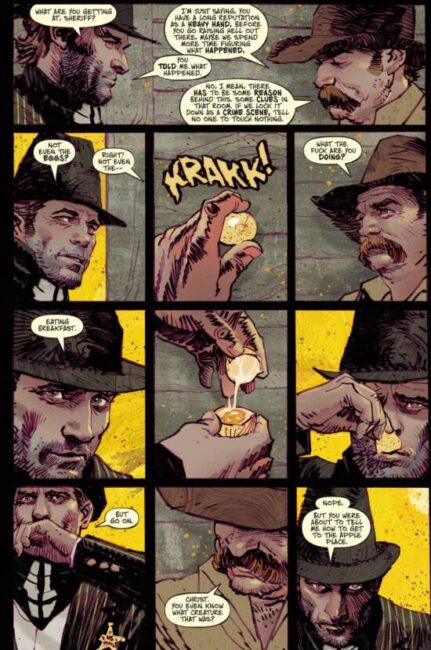

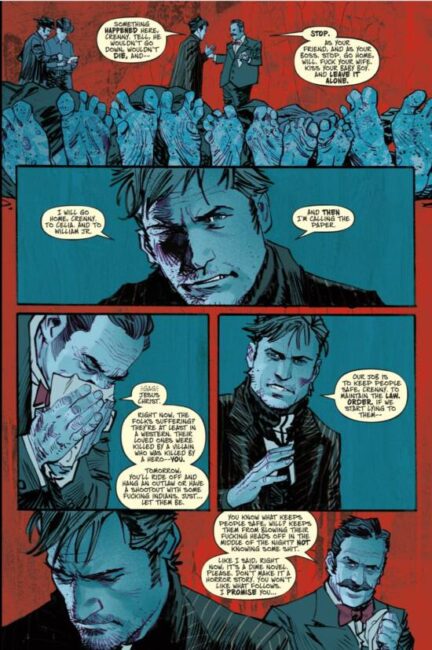

The art is very reminiscent of Blueberry by Mobius (a decades-long French series, it is worth nothing, not an American comic), or JH Williams III’s work in the mesa scenes on 2005’s Seven Soldiers of Victory: a serious of gritty line drawings by Dan Panosian which suits the harsh terrain much better than photo-realism. The art is a pleasure to contemplate, especially a full-page rendition of flowering cactii, apparently drawn by Mr Panosian simply as a demonstration of artistic prowess. Yellow hues are the predominate palette of the comic, which was perhaps inevitable, but clever regardless. As the plot gathers speeds, the colours ominously move down the spectrum, to crimson and scarlet.

Marshall Will Holt finds himself deployed to Utah, a place he knows well, in the middle of political debate about whether the territory should become an American state. A spate of horrible and inexplicable murders might have something to do with underground waterways that are sourced in mineshafts near the remote town of Canary. Holt is not a well-tempered man. “You know it’s funny, Marshall,” says a local sheriff. You ain’t such a sumbitch in the dime novels”. “Yep,” Holt replies. “That’s why they’re called fiction.”

There are some haunting scenes in this story. Johnny Apple, a small and well-behaved boy, shoots his teacher mid-class, and then blandly murders his mother as Holt tries to talk him. The fate of the many children murdered by our protagonist’s adversary, Hyrum Tell (“The Black Scourge of the Railroads” as mis-described in the title’s dime novels which form part of Holt’s back-story), is especially gruesome. It is all the more shocking because the crime is hidden in plain sight, beneath the surface of a placid lake. Tell believes he has an extra set of teeth in his throat. It evolves that he is correct. The story of Holt’s victory is so horrible that it is reworked by tabloid press into something heroic and, well, Western: a stand-off between the good guy and the bad guy resolved by fast reflexes and marksmanship, rather than a brutal fight amidst the chained, floating corpses of children.

The story has a female character named Mabel but, appropriately in our contemporary age of female equality, she is hardly fawning nor reliant in the manner of Westerns from, say, the 1960s. She has a scar dividing her brow and cheek which is never explained (and nor does it need to be) but which suggests she is not afraid of a fight. She carries the sins of her father: she becomes involved in the mystery of the murders because of a need to make good upon her father’s acts.

We also have Ed Edwards, an engineer with a doctorate, who is black, highly educated, and very out-of-place in Utah. Holt shows him respect, and Edwards notes it: ” …helping me with the luggage, sticking up for me, drinking with me. People notice. I notice.” Holt’s message to the townspeople, using his status as a celebrity and his white privilege, is subtle but obvious, but Holt plays it straight: “I don’t know what you’re talking about.” Holt, as it turns out, isn’t quite the “sumbitch” after all.

A Native American man named Wovoka, educated in a college and who knows the area, has had his nose removed so that his face resembles that of a corpse, but he is no Charon: his role within the story is initially to warn Holt and his colleagues about and away from what lies beneath, and by the end, he and his people are determined to seal the entry to hell within the mineshaft with dynamite.

We had thought that the title of the story, the skull of the mutated deer with its extra horns and malformed face, the erratic behaviour, and the mine shafts might lead us to yellow powdered uranium as being the culprit. But instead, the story veers slowly then sharply from Western into supernatural horror. In a way, this is disappointing. Evil occurs when human tripwires on morality are cut. This does not need a devil’s intervention. But some of the story’s elements require otherworldly intervention for explanation. There are miners stuck underground for years, unable to be rescued. A microphone is dropped by Dr Edwards down a shaft, and he hears them screaming for help. It is horrible to contemplate. How could they have possibly survived in the dark without food? And the answer is, of course, that they did not. When Mabel’s brother is brought to the surface, any happiness arising from the reunion is short-lived. The man’s body has changed, to an extent that is not possible by radiation. He, too, has extra teeth in his throat, and his pale body is described as being “soft like taffy”.

Our hero has a Thermopylaean ending, but the final page tells us that some secrets cannot remained buried forever. We have a glimpse of a secret society of devil worshippers with international members, arriving in Canary to ascertain the truth of events and then quickly leaving so that those events can fully unfurl. They are confronted by Holt and are unrepentant. The final page of the title, consisting of a modern four-wheel drived motor vehicle, suggests that the secret society is in existence long after our protagonists have passed away. The devil has infinite patience, Mr Snyder seems to tell us.

We have been equally critical and complimentary of Mr Snyder’s work. This story falls plainly into that later category.