(“Asterix and the Griffin”)

Writer : Jean-Yves Ferri

Art : Didier Conrad

Year : 2021

This review is based on the French edition published by Les Èditions Albert René

Russia, it seems, can be quite a cold country. Napoleon came to realize it when his troops started to collapse, leading to his greatest defeat (Waterloo, a few years later, would be the Italiann-French general’s swansong, a coda to a life some see as the embodiment of the enlightened ruler, some as the never-ending saga of the human drive towards dictatorship).

Such coldness, the moment you start losing any kind of feeling in your extremities (that is, toes and fingers), is here reproduced in Ferri and Conrad’s latest work by the Gaulish druid Panoramix’s red (and trembling) nose at the beginning of the adventure. Wrapped in what seems to be a not sufficiently warm blanket, sitting on a sleigh, he is accompanied by Asterix and Obelix on their way towards a Russian shaman, a friend of our druid’s.

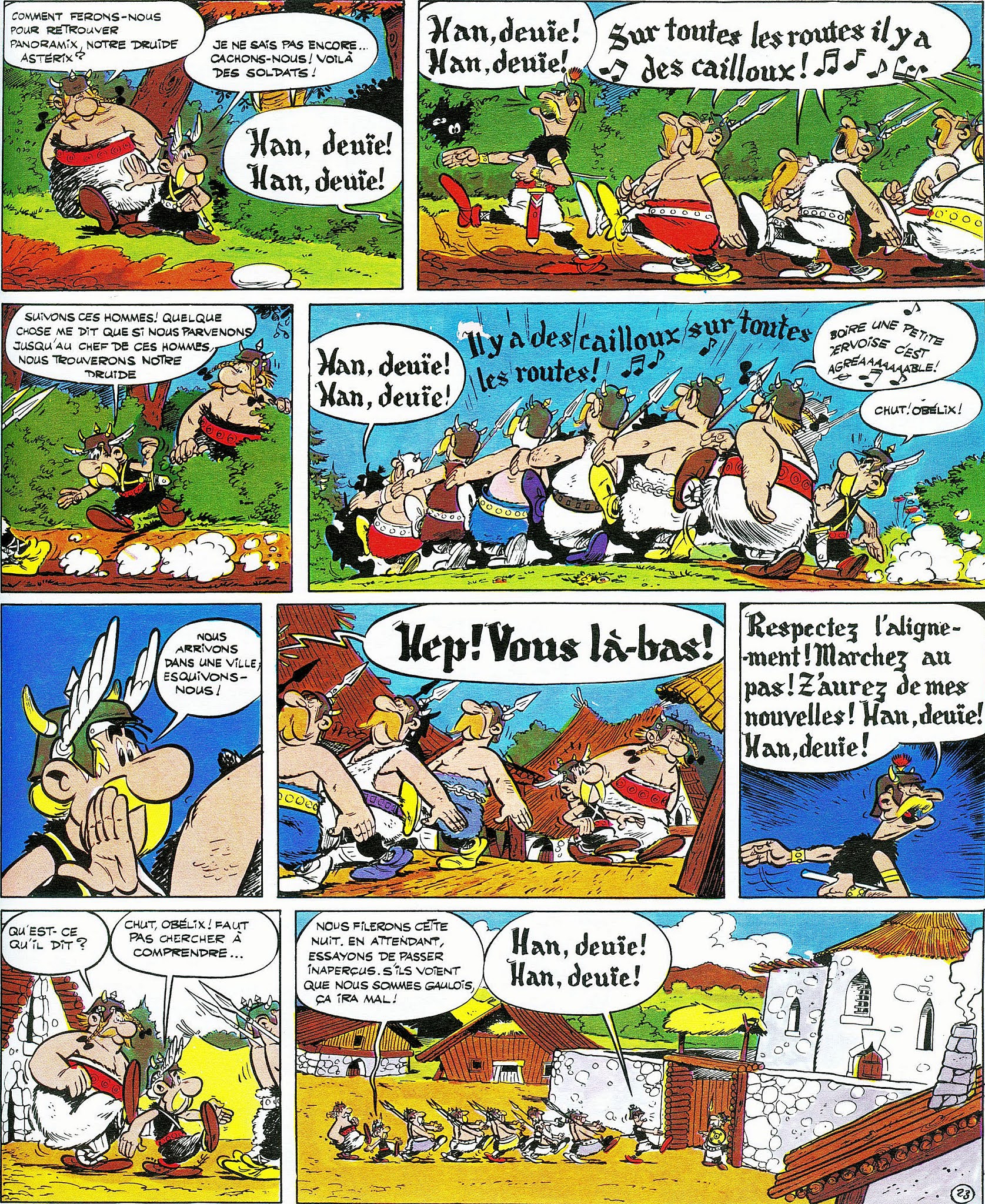

It’s a matter of serendipity. Our trio is in Russia just as a cohort of legionnaires are marching towards an unknown place where, so is it said, griffins live. Their (the Romans’) goal is to find one, capture it, and take it back to capital of the Empire, so that Caesar might show it to the people at the Colosseum and therefore receive more applause than usual.

Strange as it might seem, then, occurrences are such that they turn from chaotic accidents into fortuitous coincidences, which is akin to say that the writer (Ferri) might have told the artist (Conrad) that an adventure was to take place, no matter what, and that being that Russia had not formed part of any previous book in the Gaulish duo’s escapades, it had to be the focus of their next one.

A sloppy and infelicitous idea, some might say; a right way to put us in media res, others might retort.

What seems at first sight a disjointed mosaic of ideas thrown against the wall (let’s see what sticks and let’s stick with it), then, could actually be the main reason why this new adventure manages to do what books of this sort are made for: entertain.

But, even though entertainment per se can sometimes be a good thing, that would be putting the horse before the cart, as what matters is not just the goal, but the way the goal is (to be) reached. Of course, the end might justify the means, but in narrating a story the means are as important as the pipes in a house which make sure water not only flows, it also never spills where it shouldn’t.

If the structure is as important as the overall idea (entertain your audience), clever is the word we need to use to describe the final result of Asterix and Obelix’s incursion into the land of the cyrillic alphabet (ante litteram, in this case, but has historical truth ever played such a gigantic role even in Goscinny and Uderzo’s original stories?).

It’s a fun ride, then, not just because the overall story is good, but also because the details have been positioned so to explode, either panel after panel or in just a single instance, creating a seismic effect of detonations following detonations, the result being a chuckle making its way on our face as we delve deeper into the narrative.

So, as readers, we are led to enjoying the story as it unfolds in front of us, knowing quite well it has to end in such a way that (a) the Romans’ expedition is foiled, (b) Asterix and Obelix play a crucial role in it, and (c) there’s a banquet at the end because all is well that ends well (otherwise, why read any book based on Uderzo and Goscinny’s characters?).

But the princess here, for instance, is saved not because the prince (or princes) fights against a dragon (or any kind of evil keeper), rather because by just being beautiful she manages to have his jailers fall in love with her.

And her role, here, is such that it shows how chaotically funny the story itself is: we, the readers, are to believe she is going to be such a in important character just by way of her being presented, in all her majesty, right at the beginning, only to have all our expectations subverted with cleverness, and see her becoming a secondary (if not tertiary) character: and, after all, was she even a princess?

Of course, the main theme underlying this adventure is what reality actually is and what fiction (and its mother, the tongue that tells lies) does. Griffins were supposed to exist (reads the accounts of the Greek geographer), so looking for them in the cold region of Eastern Europe would be based on more than just a dreamy wish (that is, Caesar’s wish to be celebrated as being as great – and as real – as that winged creature), yet the final encounter is such that we are left thinking that the world we inhabit is full of wonders more incredible than those mythical figures (mythical animals, that is) would have us believe.

The story ends, then, and we can put the book right next to all that came before it, hoping that what’s to come won’t lose its sweet cleverness and its tongue-in-cheek attitude that is not only a nod to Uderzo and Goscinny, but also the realization that, after so many years of the Gaulish duo’s adventures, we can also expect to play with the very elements that make up their structure. Bonaparte lost its battle and died isolated, but the Armorican village keeps resisting the intruders as our heroes go on living in our imagination.