In this comparative review, we compare two quite different American titles, with action set in the late 1930s and early 1940s, published within a year of each other in the early 1980s. Our conclusion is that they share a surprisingly similar core premise.

We cover only two periods of each title: the original series of The Rocketeer by writer and (meticulous) artist Dave Stephens, and only what we regard as the halcyon days of All-Star Squadron (issues 1 to 30).

Barnstorming

It is 1937 and Cliff Secord, a young stunt pilot, in an age where there was no real aviation regulation, is frustrated with the top casual nature of his relationship with a beautiful woman named Betty.

Cliff recognises that what he has with Betty is quicksilver and he longs for what he cannot possess.

And as for Betty, she knows that Cliff is not a long term prospect and that she can get ahead in life by relying upon her curves and willingness to model for riske photographs.

Out of the blue, so to speak, Cliff and his mechanic sidekick Peevey stumble across a stolen experimental jet pack. Nazi agents try to recover it. Cliff uses the device to fight the Nazis, and his girlfriend is kidnapped as part of the process.

It was a threadbare plot, but still, enough to support a motion picture. The Rocketeer was first issued in 1982, perpetuated by a variety of publishers, and eventually gave rise to a film released in 1991.

Love Interest

The overwhelming sense that a reader gets from the title is that The Rocketeer was a labour of love for Mr Stephens.

It may not be immediately apparent, but in our view, the main protagonist is Betty. Betty is a blatant tribute to Bettie Page. Mr Stephens does not spare the reader the details of her flesh, perhaps most famously, when Cliff (to his fury) stumbles into a very private photo shoot.

Betty is the member of the cast with the most characterisation. She is clearly more than fond of Cliff, but she knows he is jealous and stands in the way of her ambitions. There is no guile with Betty: she knows what she wants and knows the quickest way to get there is to use what she has.

Betty gets the best lines and the best facial expressions, and notwithstanding the cheesecake veneer, the impression is that Mr Stephens was very sympathetic to the character. Betty is not a mere damsel in distress fawning over the hero. She is the one in control of the relationship with Cliff, and when she leaves for Los Angeles at the end of the story, Cliff, angry at her lack of appreciation for his efforts at saving her and foiling a Nazi spy ring, steals a plane from the flying circus and pursues her. (Thus ends the first story from the title. More have sporadically followed over the decades. Mr Stephens passed away in and since then other writers have continued Cliff’s adventures.)

In December 2009 American publisher IDW published the collected Rocketeer works as The Rocketeer: The Complete Adventures Deluxe Edition. It quickly sold out. No doubt the nostalgic appeal of the story had a lot to do with its commercial success. It is a pulp adventure, racier than comic books of the time, where the thuggish, stereotyped villains are defeated and the good guy does not quite get the girl. There is an element of attracting historical simplicity about the story – “things were less complicated in the old days”. Cliff is a man and does what men should do in 1937: brawl and haplessly pursue his true love. Nazis haunt America, but there is no war. Aircraft are a risky business, flown by crazy barnstormers, and are not yet mass produced and regulated in any meaningful way. Pre-war America had not yet been transformed into a world power with unparalleled military and industrial might.

Wartime Restraint

Our point of comparison is Roy Thomas’s All-Star Squadron publishedby DC Comics from 1981 (only a year earlier than The Rocketeer) and concluding in 1987.This title was the vehicle for Mr Thomas’ love and knowledge of the Golden Age of American comics. It is set in 1941, a few years after the backdrop to The Rocketeer, and begins with the Japanese surprise air attack on Pearl Harbour in Hawaii.

Mr Thomas brought together as many of DC Comics’ 1940s characters as he could – and there were a lot of them – and hammered them into a single continuity. That hammering was masterful but inevitably imperfect, and it gave rise to the industry term “retcon”. As Mr Thomas explained in a letters page of All-Star Squadron #20 (April 1983) this means “retroactive continuity”: the process of creating a history for the characters and erasing that which does not fit.

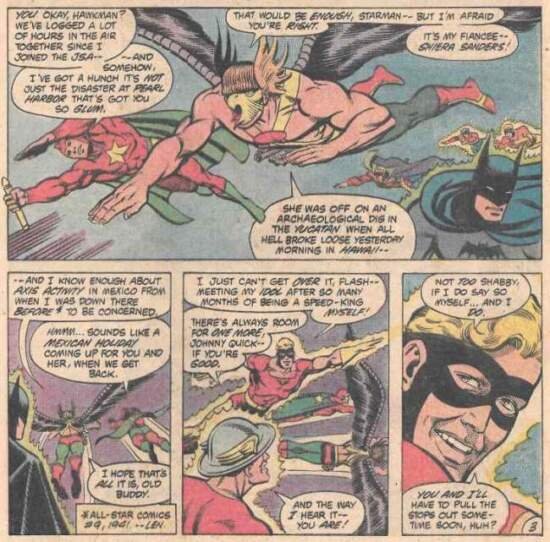

The five main characters are very minor in the scheme of things: Robotman, a wartime hero called Steel (actually created in the 1970s), Firebrand, Johnny Quick, and Liberty Belle. The better-known and revered characters from the Justice Society of America (the first superhero team) regularly appeared, particularly Hawkman, but also Sandman, The Flash, and Wonder Woman. While Cliff Secord was an accidental hero, acting in instinct while caught up in the moment, the cast of the All-Star Squadron are all self-assured in their wildly coloured costumes, collectively America’s first line of super-powered defence against the Axis.

Here, we have America at war. The country has been deployed for mass industrial production of warplanes, tanks and ships and indeed some of the action takes place in wartime factories. Most of the Justice Society are in the US Army, save for the goofy Johnny Thunder who is in the US Navy.

In a haunting dream sequence caused by the Justice Society’s nemesis Brain Wave, the Justice Society’s members fight Japanese forced in the Pacific. Hawkman riddles enemy aircraft with machine gun fire, Wonder Woman literally crushes Japanese infantry on an island beach, Starman useshis Cosmic Rod to liberate the Aleutian Islands, and Green Lantern destroys Tokyo with his power ring. In another story, The Sandman’s girlfriend is killed by Nazi spies when they shoot out the tyre of her car, causing it to crash: her bloody body is removed from the wreck by The Sandman. The title has gritty, wartime moments, far removed from the pre-war Rocketeer.

The art for the first thirty or so issues was inked and then penciled by Jerry Ordway. This was perhaps Mr Ordway’s best work. Making such an enormous jumble of characters in bright costumes stand out from each other was not just the job of the colourist. Mr Ordway’s delineated each of the cast members was superb, ranging from small features like Liberty Belle’s overbite to Batman’s 1940s distinctive costume and cape.

The art reflected the clean cut morality brought by Mr Thomas to the title. Hawkgirl, tied up and about to be sacrificed by evil Aztecs, might have jutting breasts, and Firebrand apparently sleeps nude, but there was otherwise no hint of sexuality in the title, very far away from The Rocketeer. A major villain, the Ultra-Humanite, has his brain transferred into the body of a beautiful and voluptuous movie actress. When a creepy henchman named Deathbolt lays down some moves, the Ultra-Humanite is not amused:-

Perhaps the Ultra-Humanite should have worn a lab coat instead of tight leather. In any event, none of the characters so much as kiss, even the established couples such as Hawkman and Hawkgirl, let alone have sex.

Indeed, the only romance in the story is between Johnny Quick and Liberty Belle. Johnny Quick is a hothead with an inferior complex to another speedster, The Flash. Liberty Belle is different. Smart and quick thinking, Liberty Belle is the chairwoman of the All-Star Squadron, surely the only government-sanctioned fighting force in World War Two lead by a woman. Liberty Belle was not the only female leader of a superhero group in the 1980s. A correspondent in the letter column of All-Star Squadron notes that the female magician Zatanna chaired the Justice League of America, and Marvel Comics’ Avengers was at that stage lead by The Wasp. But Liberty Belle is the only one who was effective.

Both Liberty Belle and Johnny Quick are newspaper journalists. Johnny is a little obsessed with Liberty Belle, and does not steer the relationship at all:

In that regard Liberty Belle’s relationship with Johnny Quick is decidedly similar to that of Bettie and Cliff in The Rocketeer. Bettie and Liberty Belle on the face of it do not have very much in common: Bettie is happy to sell nude photographs of herself to make a buck and propel her career, while Liberty Belle commands the respect of US President Franklin Roosevelt. But both determine their own destiny, and both are not subservient to their male admirers. In that regard, for superhero comic books set in the late 1930s/early 1940s, there is a surprising feminist paradigm underpinning both titles. Bettie does as she pleases, and Liberty Belle does what she thinks is best.

While The Rocketeer has been republished as a collected work, All Star Squadron remains only capable of being read in the original individual issues – a significant oversight by DC Comics.