Writer: Kieron Gillen

Artist: Jamie McKelvie

Image Comics, October 2019

It has, with respect, been a bumpy ride for committed readers of The Wicked + The Divine. This highly innovative series written by Kieron Gillen and with art by Jamie McKelvie began with the premise of a 90 year cycle of archetypes plucked from The Golden Bough, but with each character carrying the burden of knowing that they would be dead within two years.

In the 1940s, comic book characters battled Nazis: in the 1980s they fought against the Soviet threat: in the 2010s they party on social media. Combining super-powered deification with the contemporary obsessions of fame via technology lead to a compelling and crazy plot. We have reviewed volumes this title before, starting back in 2015: see https://worldcomicbookreview.com/2018/10/19/the-wicked-the-divine-mothering-invention-volume-7-review/ and https://worldcomicbookreview.com/2015/06/26/the-wicked-the-divine-the-faust-act-or-how-kanye-west-became-a-god/

But somewhere along the way we think the title became convoluted for the sake of being convoluted. A roller coaster is one thing: a maze is another. This final volume, entitled “Okay”, concludes the story and tries to go some way towards weaving in those odd and superfluous aspects of the plot.

The villain of the play is an ageless woman named Ananke. We have learned that some of the key characters had not died through what seemed to be inevitable self-destruction or at the hands (or rather, clicking fingers) of Ananke. Instead, their decapitated but living heads sat, oddly, in a candlelit crypt, chatting away about their plight.

It is almost Monty Python-sequel, and was a jarring and weird interlude to the plot. This afterlife is in furtherance of a curse, of sorts, dating back thousands of years. One of the characters, Sakmet, dodged time in the crypt because her death did not involve the clean separation of her head from her neck. A ragged incision does not meet the terms of the curse.

None of this was foreshadowed in the beginning, and it is not effectively explained by this ninth volume. It is a wobbly plot mechanism to bring some of the dead characters, particularly the female incarnation of Lucifer, who was the first significant victim way back in the first volume. Being a head in a bookshelf was an ignoble post-life existence for some of those characters who were happiest in a nightclub. And it was a strange change of pace for a cast who were doing a perfectly good job of burning themselves out on drugs, sex, fame, and regret.

Some of their actions are regretted, and some are not. The lead character, Laura/ Persephone, in this ninth volume faces a criminal court for a flagrant murder caught on video and with no possible defence or justification. With a slight smirk, she seems to regard jail as an appropriate capstone to her demolition of the millennium-old horror of incarnation of god-like creatures. She is apparently sentenced to “life”. But life as a sentence seems preferable to the death that was dealt by Ananke over the centuries.

Ananke’s death is terrible: a murder-suicide by a guilt-ridden Baal (“descended” to his human self, Valentine) who casts himself and Ananke from the top of a building. The mashed bodies can be seen in a high angled panel from artist, Jamie McKelvie. Ananke enjoys rotating phases of existence as crone and maiden. At the point of her murder she is a young girl, and, further, is stripped of her sorcery and defenceless. But Valentine decided not to take the risk that Ananke might somehow outplay the endgame, and by reason of his own actions as a serial murderer of children had a very heavy price to pay.

Despite the violence, we initially thought that this latest volume had a decidedly “next day” smell to it. The mental state of partygoers that the festival is over, the fun is concluded, the hangover has set in, and that there are consequences to actions. The party rolled on and became sordid and nasty: the muddled craziness of the plot eventually ended with a slow crash of sobriety.

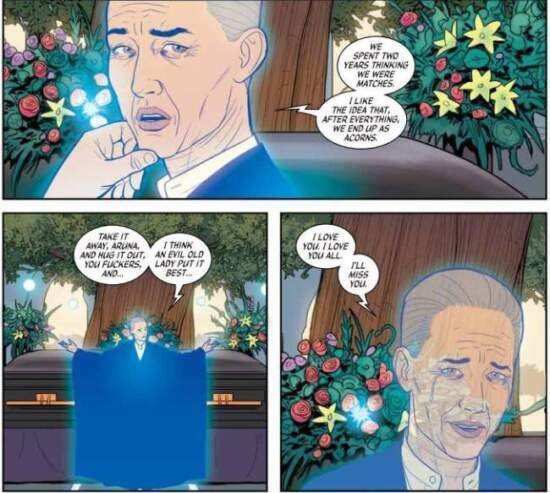

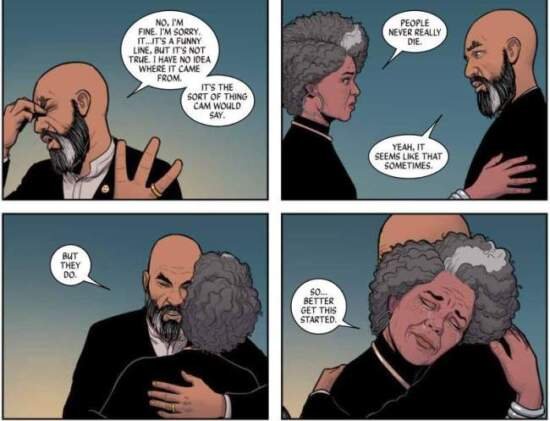

But now we think that the conclusion to the story, set in the future, has a different theme. The teens of the 1920s must have felt like this in the 1960s: Free love hippies must have felt like this in the 2000s, and clubbers from the 1990s will certainly feel like this next decade. There is Epimethean wisdom, some regrets, unfinished business, and a final goodbye. Wakes are from experience strange experiences where attendees have spent their grief at the funeral and, after, catch up and drink with rarely-seen friends with that tinge of guilt about having a good time. The coda in “Okay” captures this perfectly. There are the awkward discussions between those who were once friends and lovers but who grew distant over time, those unfinished conversations at funerals that will never be satisfactorily concluded. Seeing someone one last time frequently occurs at wakes, and rarely are there more than pleasantries which whitewash the hurt or loss from long ago. No one walks away happier or with a sense of cathartic release. Things are left unsaid. Mr Gillen captures this perfectly.

The characters who attend the funeral are almost unrecognisable through age. It is not evident during the rush of youth, but twenty-four hour party people do eventually grow up and grow old. Persephone is there, her hair grown back over the decades into its long tight curls now rendered silver-grey but still strikingly beautiful. (Mr McKelvie draws all of his characters with such symmetrical and wondrous beauty, such that we wonder whether he could ever draw an ugly face.)

As a conclusion, Persephone addresses the reader. The monologue seems to chide those who envied the power and glory of the characters. You make your own destiny, Persephone says. And to underscore the point, the last few pages of the volume are blank, a story to be written by the individual readers, not by the creators and certainly not by the characters. (We have had to resist the temptation to clumsily draw in a scene set in a dark and stormy night where Ananke’s clawed hand is thrust up through mud.)

What to make of all of this? There are loose ends, common to all epics. How is that Persephone still had a subdued version of her powers, enough to save the survivors from being shot by police? How did Tara manage to survive for decades with no body, once the magic had gone? What was the point of the initial gamble between the sisters thousands of years before and what on earth did it mean other than garble?

But the evil, thousands of years old, is ended. Most of the cast survive, their superstar status as avatars concluded. Those undeserving and cruel are dead. Would the series have been more intriguing if Ananke had prevailed, with a flash-forward to the next iteration of the Recurrence in ninety years, to witness Ananke at work again? Or if Ananke was actually the hero and Persephone was the villain (you get the sense that the story was heading that way for a while)? Or if a third party had leaned in to scatter the pieces across the board? The fact that we are asking these questions of ourselves suggests that we are uncertain of the finale, and wonder if it could have been done better. We are reminded of Saul Bellow: “Any artist should be grateful for a naive grace which puts him beyond the need to reason elaborately.”

Regardless, we will genuinely miss this title.