A deluxe, tenth anniversary edition of Brother Lono was published by DC Comics in 2024. Here is the publisher’s all-too-brief promotional copy:

The Eisner Award-winning team of writer Brian Azzarello and artist Eduardo Risso returns to the 100 Bullets saga for a tale of shattered trust and blood vengeance.

Brother Lono is a violence-riddled crime story set in Durango, Mexico. Lono was one of the few main characters to survive the final conflagration in the crime/conspiracy comic book title 100 Bullets (1999-2009), that masterpiece of noir fiction written by Brian Azzarello and with luscious art by Eduardo Risso.

But why should one of them been Lono? Perhaps it is because of his popularity amongst readers, something we have always struggled with. From 100 Bullets: Brother Lono #1 Review:

Lono was my favourite character of the series, ever since his silent introduction in issue 5, where he single handedly took on a helicopter. Since he continued to prove himself, a larger than life beast of a man whose only code in life was that he could what he wanted when he wanted to anything and anyone.

Is Lono a millennial example of toxic masculinity? We have sometimes wondered if readers saw Lono as some sort of darker version of Marvel Comics’ very popular ninja/brawler/superhero Wolverine, as set out here: Brother Lono | Slings & Arrows –

“Five years after they wound up the stunning 100 Bullets, Brian Azzarello and Eduardo Risso reunited for a spotlight on that series’ most popular character. Lono was like a bulkier Wolverine, big, but not the biggest guy on the block, and a scrapper who never quit, with a high tolerance for pain and injury. He revelled in what he was, yet while he could bury his psychotic tendencies for a while, there was scant warning of that facet of his character breaking out, and little regret when it did.”

Critic Chase Magnett obliquely asks the same question as us – Brother Lono #8 Review – Magnett Academy:

“It turns out that Lono is still the same sociopath that fans came to know and (improbably) love in 100 Bullets.”‘

Oddly, we do not talk at all about Lono in part 1 of this series of reviews: “100 Bullets” revisited, Part 1 of 3: Croatoa, MK Ultra, and the induced amnesia of the Minutemen – World Comic Book Review.

Lono was a Minuteman: an enforcer who carried out violent missions for The Trust, a secretive organisation of powerful families who controlled the United States under a centuries-old pact. Lono’s brutality was evident in details such as the beheading of the two young sons and mutilation of a rogue member of The Trust; surround by gore, the decapitated heads with faces fixed in screams, and the chained and hanging body of their father, Lono casually makes a phone call as if he was ordering a pizza. And Lono did worse than that, acts which we will not describe for fear of attracting the wrong sort of search engine traffic. Lono’s lack of remorse, and near-psychotic tendencies, made him a completely reprehensible character. He was the worst of a very bad bunch. Again, we do not understand the attraction.

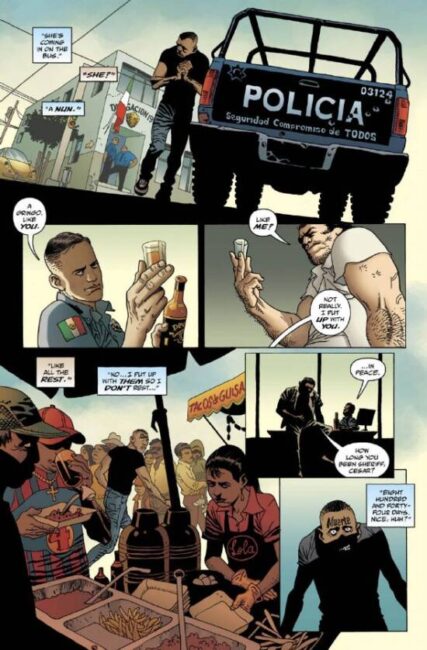

In this postscript story, Mr Azzarello zags when we thought he might have zigged. Rather than Lono landing in Mexico as some sort of assassin, our first glimpse of the bullet-scarred former warlord is dressed in white with a perturbed look on his face. Lono finds himself transformed into a gentle Christian brother working in San Sebastien Orphanage, located outside Durango. Rather surprisingly, Lono is not in hiding from the final events of 100 Bullets, and instead genuinely tries to walk the path of redemption.

But the escalating violence and moral decay around him constantly test his resolve, to the point that he frequently locks himself voluntarily away in a prison cell so as to avoid temptation. Pastoral care alone is not enough.

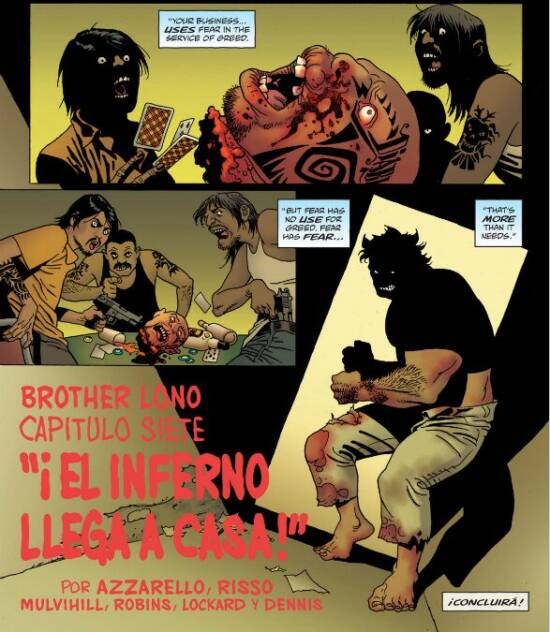

The story builds tension as Lono is at first pushed, but then glides back into the persona of savagery. It is a story which tells us that some people simply cannot change. (We see this often enough in American superhero comics: a crimefighter calls it a day, but is slowly lured back into battling evil. Perhaps the most famous example of this in comics is The Dark Knight Returns, where Frank Miller portrays the long-retired Batman as possessed by his demons, and his efforts at keeping them submerged are doomed.) In Brother Lono, although he works in an orphanage, it is not the desire to protect children from the cartel members which causes Lono to finally and decisively act. Nor is it his torture at the hands of the drug lord, Craneo, which pushes him over. It is instead the surrounding atrocities, including cartel brutality and exploitation, which together serve as a catalyst for Lono’s return to violence.

Thinking of the setting of the story, this representation of an initially subdued Lono seems to be akin to a Saguaro Cactus (Carnegiea gigantea), which is inert and peaceful for long periods of time, and which only flowers during desert rainfall. Lono finally blossoms into violence when the ground is fertile with blood.

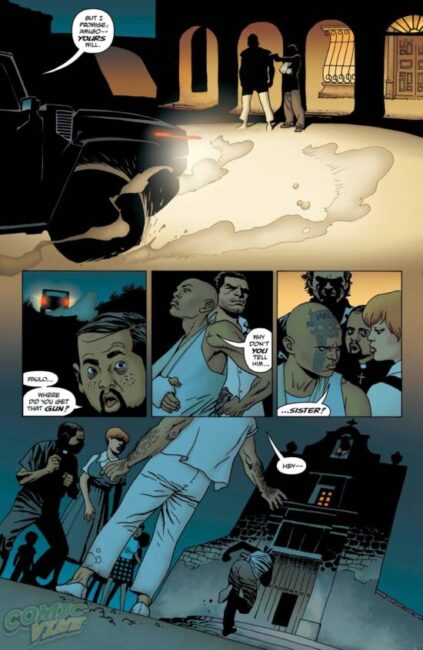

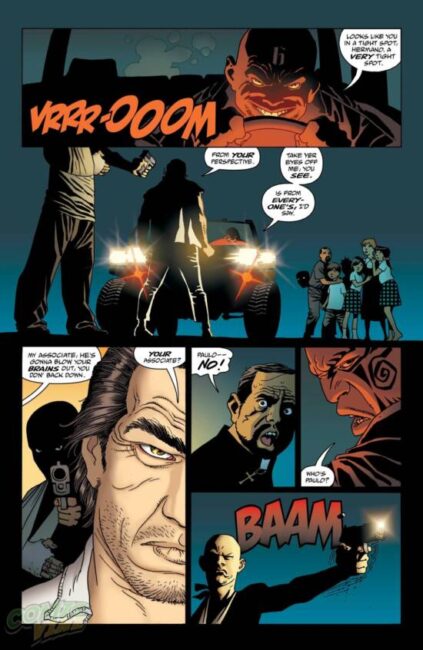

Brother Lono has a small supporting cast compared to the many players in 100 Bullets. Only two stand out as particularly interesting. Sister June describes herself as nun who arrives in Durango, to work at the San Sebastian Orphanage. She is introduced early in the story when Lono picks her up from the bus depot. Mr Risso portrays Sister June as something other than a demure nun: she is pouty, busty, and attractive. Her immediate shock at seeing a dead body in the street (Ernesto, a victim of the local drug cartel) is in time revealed as a performance. She is in fact Agent May (“June” rolls back to “May”, a typical wordplay by Mr Azzarello), from the US Drug Enforcement Agency. She survives the story, albeit with a gunshot wound to the abdomen. Agent May’s role in the story, we think, is simply to add additional tension to the story, especially when one of the cartel members (Paulo) overhears her report to her superiors: we had assumed that her destiny from that point was going to be a shallow grave.

Mr Risso’s art as always is excellent, especially in respect of facial expressions. We are very used to Mr Risso detailing graphic violence from 100 Bullets. In Brother Lono, however, it is his depictions of the tattoos on the faces of the cartel members which multiply the unease generated by the story. The second, and most interesting character in the story is Paulo, a young man who grew up in the orphanage and, lost in life, joined a cartel. Paulo is unrecognisable from the young boy he once was. Mr Risso draws Paulo’s face as covered in an inked skull, tyre tracks, and the word “malo” across his forehead, identifying him as beyond redemption.

And yet Paulo goes where Lono ultimately cannot. When he finds himself unexpectedly back at the orphanage, Paulo realises how far he has strayed. He stands up against Craneo, ultimately losing his life in the defence of what he has lost. Compared to Lono, Paulo is the better man.

Brother Lono is a bleak tale which hurtles towards a violent finale. It is a long way from cathartic in any sense, other than Paulo’s martyrdom. Lono does not receive spiritual release from his sins and his past. Instead, in the final scene, he is depictured as a blood-smeared devil in his dark lair, smoking a cigar and drinking whiskey.