Writer: Karla Nappi

Artist: Mariana Strychowska

This is an independent science fiction comic published in October 2018, and set in 2060. It is written by Karla Nappi, with art by Mariana Strychowska.

Ms Nappi refers to the genre of the title as “biopunk”. “Biopunk” is a new term to us, and we were compelled to look to Wikipedia to learn of it – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Biopunk . This title contains concepts which would not be out of place in a William Gibson or Bruce Sterling novel – holographic funerals, translucent electronic tablets, a robot street sweeper, the failed state. But there is within biopunk an emphasis on biotechnology, and in this case, the use of nanotechnological robots which support artificial organs.

The suffix “punk” describes the illicit in science fiction, and sure enough, we have organ harvesting from live subjects, and illegal and lethal fail-safes sneakily built into the nano-robots.

The title is very much orientated towards ethical considerations of biotechnology. Ethics and artificial organs sounds very contemporary, but scholarly consideration of the concept dates back to at least 1964 – see https://journals.lww.com/asaiojournal/Citation/1964/10000/Ethical_Problems_of_Using_Artificial_Organs_to.40.aspx . In this more recent article https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27875647 by Hutchinson and Sparrow, entitled What Pacemakers Can Teach Us about the Ethics of Maintaining Artificial Organs, the authors concern themselves with post-operative care:

One day soon it may be possible to replace a failing heart, liver, or kidney with a long-lasting mechanical replacement or perhaps even with a 3-D printed version based on the patient’s own tissue. Such artificial organs could make transplant waiting lists and immunosuppression a thing of the past. Supposing that this happens, what will the ongoing care of people with these implants involve? In particular, how will the need to maintain the functioning of artificial organs over an extended period affect patients and their doctors and the responsibilities of those who manufacture such devices? Drawing on lessons from the history of the cardiac pacemaker, this article offers an initial survey of the ethical issues posed by the need to maintain and service artificial organs. We briefly outline the nature and history of cardiac pacemakers, with a particular focus on the need for technical support, maintenance, and replacement of these devices. Drawing on the existing medical literature and on our conversations and correspondence with cardiologists, regulators, and manufacturers, we describe five sources of ethical issues associated with pacemaker maintenance: the location of the devices inside the human body, such that maintenance generates surgical risks; the complexity of the devices, which increases the risk of harms to patients as well as introducing potential injustices in access to treatment; the role of software-particularly software that can be remotely accessed-in the functioning of the devices, which generates privacy and security issues; the impact of continual development and improvement of the device; and the influence of commercial interests in the context of a medical device market in which there are several competing products. Finally, we offer some initial suggestions as to how these questions should be answered.

Many of these concerns feature in this thoughtful title.

We open with the strike of a disease called the organ failure pandemic. In a scene very reminiscent of the gory beginning of Y:The Last Man (Vertigo Comics, 2002-2008), we see bodies scattered and bleeding, the backdrop a futuristic hospital. This opening scene, rendered with mastery by Ms Strychowska, is striking. In a single panel, Ms Strychowska communicates that the global effect of the plague by way of the very high perspective, and the high-tech hospital is an indicia of the powerlessness of medicine in the face of the plague.

Ten percent of humanity is afflicted. An evil corporation called Regenerist Tech also appears in the prologue, along with Matt Travers, who has invented organ duplication technology. Travers seems like a man with good intentions but is hooded with corporate blinkers, and it is eventually apparent he is the protagonist of the piece. In many ways, Travers reminds us of contemporary technologist billionaires who inhabit mostly Silicon Valley, seeking to improve humankind, but who are not keeping their eye on the cultural ball and so are spawning distrust.

Pamela Wilton, a paralegal trying to pass the bar, born on December 19, 2030, has failed lungs and no money to pay. After being saved, her life is auctioned off. She is exposed to prejudice (“Why do they even let those people out after being sick?”), and finds herself reporting to work at a business called Toressi Investments. Pamela meets the pleasant Mr Toressi, who, after a conversation to do with pancakes verses waffles, tells Pamela that she will be a prostitute. He rapes her on a “date”, leaving her weeping in the shower. “I know the law,” says Pamela. “I know that whoever purchased my debt… had the legal right to employ me however they see fit, but…” Pamela is just like any victim in a time of plague, with her destiny out of her control, but with the overlay of bleak, horrible indentured servitude. She is a very sympathetic character.

Pamela’s friend Beth belongs to a cult which believes that the plague is a sham. Pamela starts to buy into the concept, decides to rebel, and seeks out Travers. She assaults Toressi and evades his loathsome bodyguards. A confrontation follows, which sets Travers down a guilt-carved pathway towards the truth.

Ms Nappi says,

DUPLICANT came from my love of dystopian future movies like Minority Report, Blade Runner, and a little known movie called Repo: The Genetic Opera. The idea of repo men for organs struck a creative chord in me, and I decided to do my own unique twist on it.

In DUPLICANT, the organs are manufactured. This idea came from my interest in science, and specifically nanotechnology and 3D printing. The cost of these manufactured organs is so high that you’re essentially sold to the highest bidder to pay off the debt. The human organ trade is illegal. My personal path to the arts came via writing. I worked in New York City and Los Angeles as a writer and script coordinator for over a decade. This training ground helped prepare me for writing my true love, comic books. I was fortunate to bring DUPLICANT to life in a series of workshops at Meltdown Comics before they shuttered their famous doors. I feel incredibly lucky to be part of this great community that has garnered me some of my closest friends and colleagues

Shades of Blade Runner are certainly visible in the idea of enslaved humans who are no more than biotechnological creations, and out of control corporations who see humans as either consumers or assets.

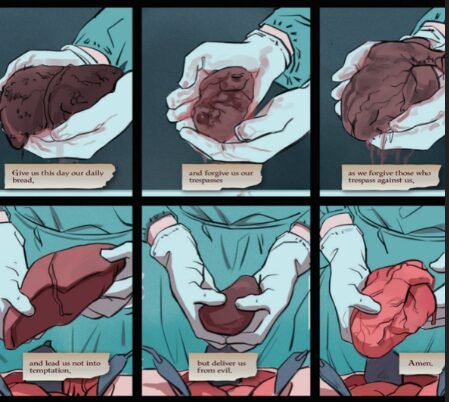

Ms Nappi’s innovative concepts are supported wonderfully by Ms Strychowska’s art. In these scene, we have the metaphor of a heart as a trespasser, with a heart removal surgery accompanied by the Lord’s Prayer:

Religion does not often feature in near-future science fiction, other than as a relic – see for example, the Luddite Russian Orthodox mob in Drugs and Wires https://worldcomicbookreview.com/2019/03/18/drugs-and-wires-down-in-a-hole-review-volume-1/ But religion is place humans turn to when plagues strike, often evidenced by the building of churches: in Venice, the Madonna della Salute cathedral commemorates the end of a terrible plague which between 1630 and 1631 decimated the population of Venice. The Venice Republic made a vow to the Virgin Mary, promising that if the plague was finally over, they would build a new church dedicated to her. But Ms Nappi understands that religions are not necessarily inherently good. The introduction of religion into this story, as a source of solace, a secret chamber for rebellion, and with its own malign motivations, is either inspired, intuitive, or both.

More about this disturbing and engaging title can be found at http://www.karlanappi.com/writing.html . A Kickstarter campaign for Duplicant starts on 15 January 2020 – see https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/2007016434/duplicant-1-and-2-dystopian-future-biopunk-sci-fi-comic