As tensions between the West and Russia have dramatically increased in the past year, so too has the characterisation of Russia in Western comic books.

As we discuss below, most of Western comics’ attention this century has been directed towards the menace of the Soviet Union and its state-sponsored spread of communism as an ideology and a system of government antithetical to Western democracy and capitalism. But in the past five years, particularly, there is a new orientation towards perceptions of Russia in comic books.

In addition, we also take a quick look at the contemporary Russian comic book industry, and its penchant for copying American concepts.

1. Vladimir Putin and Post-Soviet Russia

A brief rundown of the geopolitical sequence of events leading to where we are now is worthwhile:

a. In 2008, Russia militarily annexed the two ethnic Russian states of Abhkazia and South Ossetia from Georgia, constituting a substantial grab of Georgian territory. The West responded with sanctions, but as crude oil at all-time high of $145 a barrel in July 2008, these sanctions had little impact. (The Russian economy is to a very significant extent reliant upon oil.)

b. Oil prices go down because of shale oil

c. Russians become unhappy as the price of everything goes up as oil was propping up economy.

d. Russian President Vladimir Putin says this drop in the oil is a Western conspiracy, aided by the Saudis. This coincided with increased Russian air force buzzing of Western allies as reported in 2011.

e. Russia distracts its citizens with an invasion of Ukraine and in July 2014 a Russian missile shoots down a Malaysian passenger jet killing all occupants. NATO fails to challenge any of this militarily. However, by December 2014 Ukraine entered into cooperation agreement with NATO.

g. Oil prices continue to spiral. By June 2014 the price of oil had fallen to $115 a barrel. But by February 2015, oil had plummeted to $35 a barrel. In addition, Western sanctions over Ukraine and the destruction of the Malaysian commercial jet start to bite. This includes Russian companies losing access to Western credit, and thereby unable to refinance debt.

h. Russia again distracts its citizens from financial woes through the support of the Syrian regime in its civil war. Russia refuses to engage in airspace protocol with Western combat aircraft also operating in Syria, in October 2015.

i. In November 2015, Turkey shoots down a Russian military jet. Russians are very unhappy about this, and the Russian government installs heavy duty SAMs and Krashuka-4 platform (advanced jammer) in northern Syria.

j. In March 2016, Russia declared that it was pulling out of Syria – except of course it did not.

k. By February 2016, the Syrian war is very popular in Russia.

l. In April 2016, US special forces numbers dramatically increase in order to assist anti-Assad forces, and Russian jets conducted mock bombing runs, captured on video, over the guided missile destroyer USS Donald Cook, and then another Russian jet conducted a barrel roll over a US reconnaissance plane, both in the Baltic Sea.

m. By September 2016 Russian hackers are accused of interfering in US elections. In the meantime, Western sanctions are extended. More individuals are subject to asset freezes and travel bans, and Gazprom subsidiaries are directly targeted by sanctions. These sanctions bite very hard.

n. As at October 2016, crude oil currently at $50 a barrel, a very poor price – indeed, the international oil cartel, OPEC, have agreed to slow production in order to lift prices. Russia starts talking about direct war with the West in Russian media. There are Russian military drills on Ukrainian border. US policymakers distracted by election and US lawmakers in bipartisan deadlock.

Comic books are often good thermometers of international tensions. Valiant Comics have published a comic in April 2016 called “Divinity II”, where Russian president Vladimir Putin is cast as a villain intent on world domination, reliant upon two 1960s cosmonauts returned from space with superpowers. Failing to subvert Mikhail Gorbachev (by way of time travel) into preservation of the Soviet Union, and having little luck with Joseph Stalin, Vladimir Putin proves to be a much more willing accomplice.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Given recent political and military events as detailed above, it should not be especially surprising that Mr Putin is cast in American comics as a world-class villain akin to Hitler or Stalin.

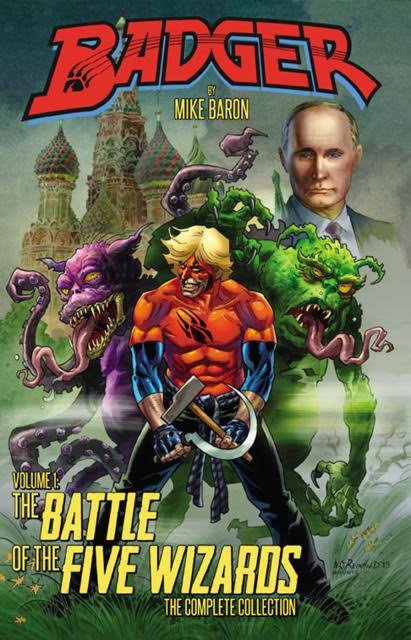

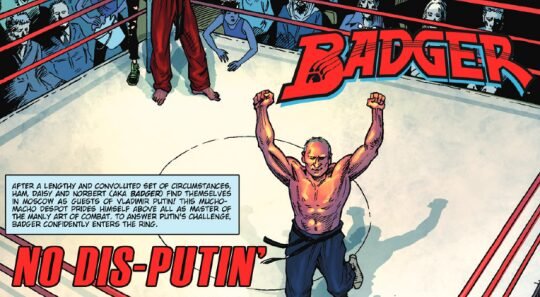

Similarly, this year, the iconic 1980s now-relaunched publisher 1First Comics’ title “Mix Tape 2016” features “Badger vs. Putin”. The Badger is a superhero with a multiple personality disorder. In this title, he cage fights Vladimir Putin, who is described as a “mucho-macho despot”:

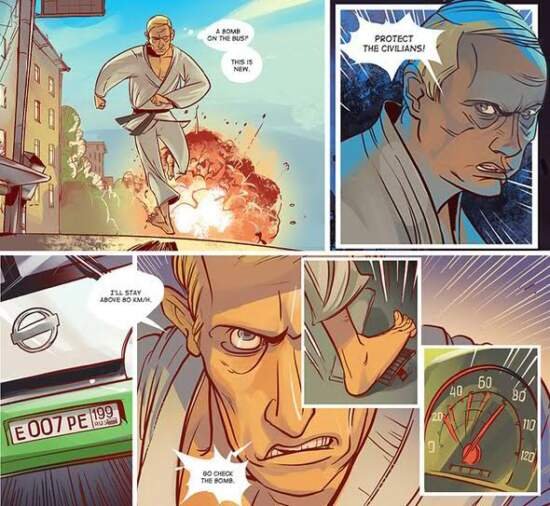

British publisher Kult Creations in “The New Amazons Preview Special” (September 2013) also has Vladimir Putin cast as a supervillain:

These visions of Mr Putin are in stark contrast to “Superputin”, a Russian comic published in 2011 in which Vladimir Putin is portrayed as a martial arts superhero and vice-president Dmitri Medvedev as a trusty assistant capable of morphing into a giant bear, fighting zombie-esque democracy protestors

2. The Napoleonic Wars through to the Soviet Union

Wariness of Russia has a long history. Despite British pretensions about the Battle of Waterloo, it was Czar Alexander I’s forces which defeated the French in 1814 and occupied Paris at the conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars: Alexander was feted as the victor over Napoleon Bonaparte at the Congress of Vienna in 1815. For the next thirty years, Russia was regarded as Europe’s policeman.

The Russian loss in the Crimean War (1854-6) to a collation of French, Ottoman, and British forces occurred because of poor logistics infrastructure and outdated weapons and tactics despite overwhelmingly superior numbers. The following cartoons are from “Punch” (a famous satirist cartoon from the 1800s) in 1854:

The British and the Russians vied for control in Central Asia, particularly modern-day Iraq and Afghanistan, during the 1870s through to the 1910s in a proto-Cold War called “The Great Game”. Here, another image from “Punch” from 1878 and a second from 1911:

The stunning Japanese maritime victory in the Russo-Japanese war in 1905 would have resulted in a counter-attack and complete route by superior numbers of Russian land forces but for the settlement negotiated by the United States and European powers. Losing to an Asian power however was a loss of face to the Czar:

Russia fought the German army to a standstill in World War 1, pulling out only because of the Soviet revolution in 1917, and Britain was engaged in a quiet and ultimately ineffective shadow war against Lenin’s government for much of the early 1920s.

Russian claims to being the leading victorious power in World War 2 against Nazi Germany have much merit. World War Two to a degree overlapped with the Cold War, with Europe torn asunder and Eastern Europe essentially occupied as puppet regimes of the Soviet Union until 1989.

3. The Soviet Union

The overthrow and murder of the Tsar in 1919 and the replacement of the Russian Empire by the Soviet Union was regarded with intense suspicion in many parts of the West.

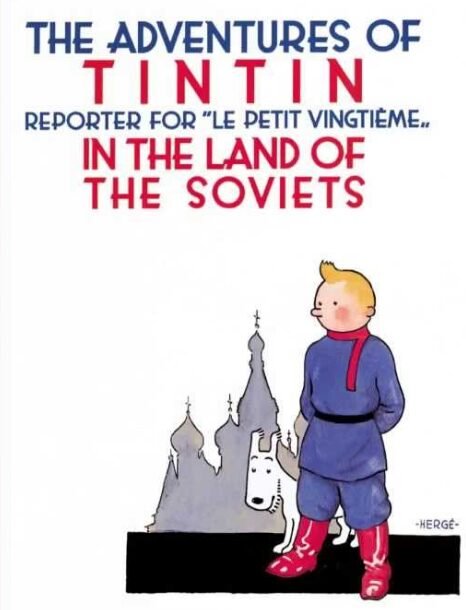

Comic books have long been a vehicle for political expression. “Tintin in the Land of the Soviets” is the first volume of “The Adventures of Tintin”, the comics series by Belgian cartoonist Hergé. Commissioned by a Belgian newspaper, Le Vingtième Siècle, it was anti-Soviet propaganda orientated towards children. “Tintin in the Land of the Soviets” was first published in 1930.

Tintin is a reporter. He is assigned to the Soviet Union and soon is involved in unpleasant escapades involving near-death at the hands of the Soviet secret police, with threats of disappearance and torture made against Tintin.

By the late 1930s, Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union enetered a period of very friendly relations. In 1939, the Molotov-Ribbontrop Non-Aggression Pact between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union was greeted with skepticism by the West:

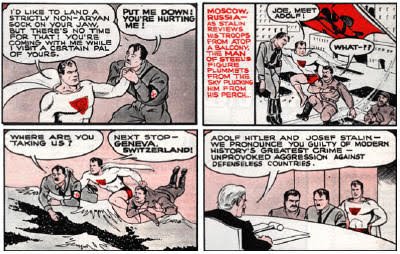

Nazi Germany ignored the Molotov-Ribbontrop Non-Agression Pact and invaded the Soviet Union. Prior to the US joining the war in 1941, DC Comics’ premier superhero character Superman was depicted as endeavouring to broker a peace between Hitler and Stalin:

After the US joined the war in 1941, the characterisation of the Soviet Union in comics changed accordingly, and was depicted as a friend and equal in the fight against the Axis:

With Hitler defeated, the Soviet Union assumed control of the Eastern European countries it had invaded in pushing back Nazi forces. As the Soviet Union rapidily assumed the role of being an existential threat to the West, the perception of the Soviet Union in comic books changed. Fear of Communist aggression filtered its way into popular culture. By 1954, Captain America was depicted fighting Soviet soldiers and radioactive monsters:

During this period, propagandist war comics also depicted American servicemen brutally fighting Soviets:

Fears of a communist planet were played upon in comic books of the time. Below is a 1947 comic book entitled “Is this Tomorrow?” published by the “Catechetical Guild Education Society” in Minnesota:

These themes in comic books of Soviet antagonism continued well into the 1970s. In 1978 in England, dystopian parody “Judge Dredd”, published by Eagle Comics, established a Soviet version of the eponymous Judge. In this title, a city of 800 million people located on the east coast of what was the United States was partially obliterated by a nuclear war, started by the Soviet Union, now known as the East Megians or Sovs. The leader of the Sovs, Bulgarin, sports a very Stalin-esque moustache. A city straddling Moscow and St Petersburg, known as East Meg One, is subsequently destroyed by the vengeful Judge Dredd using atomic weapons, with a loss of 500 million lives, in a bleak storyline published in 1982 :

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

4. Russians as Protagonists

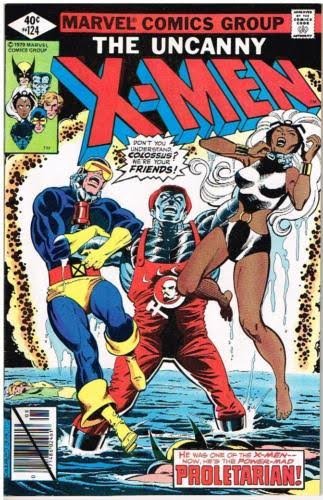

But, curiously, a singular change in attitudes towards Russians, as opposed to Russia, appeared in an American superhero comic in 1974. The introduction of Colossus, a Russian mutant superhero, to the cast of the comic title “The Uncanny X-men” was unusual. The character’s origin, set on a worker’s collective in Siberia, is set out below:

Russian strongman Joseph Stalin chose his surname as an amalgamation of the Russian word “stal” (steel) so as to intimate his demeanour, and the suffix of the surname of Vladimir Lenin (the founder of the Soviet Union). With that in mind, there was not a lot of subtlety in creators Roy Thomas and Len Wein giving Colossus the mutant power to transform his body into steel. In much more recent times, Colossus has been depicted as sporting a decidedly Stalin-esque moustache:

In this panel from 2014, Colossus is depicted with his younger sister, a mutant/sorceress named Magik, who, although ostensibly Russian, does not act like a Russian nor use Russian words (a feature of Colossus’ dialogue is the peppered use of Russian).

Early on, and perhaps inevitably, Colossus was temporarily brainwashed into a minion of the Soviet state and an enemy of his fellow X-Men:

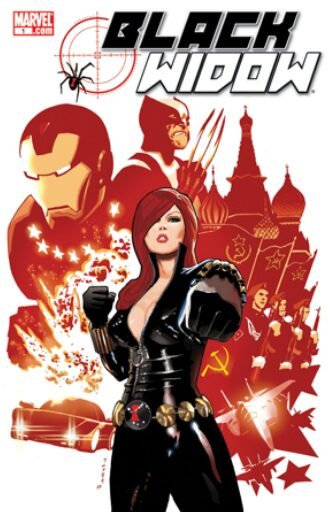

At all times Colossus has been depicted as a proud Russian. This is quite different from the best known Russian superhero, Marvel Comics’ “Black Widow”. Black Widow first appeared in in 1964, as an adversary of Marvel Comics’ superhero character Iron Man. In 1966, the character was recast as a defector to the United States, eventually joining Marvel Comics’ primary superhero ensemble, the Avengers.

Unlike Colossus, characterisation of Black Widow as a Russian is very inconsistent, and is entirely reliant upon the very rare use of an accent (most recently, in writer Matt Fraction’s “Hawkeye” in 2012).

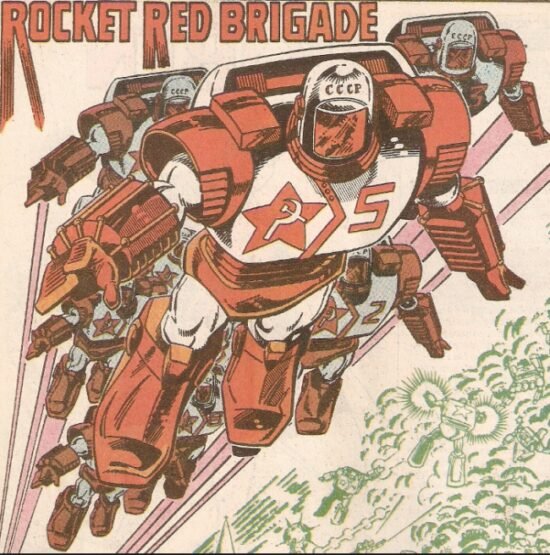

The other major publisher of comic books in the 1980s, DC Comics, also entered into a form of comic book détente with the Soviet Union. In 1987, DC Comics introduced a band of armoured superheroes called the Rocket Red Brigade, in the pages of the comic “Green Lantern Corps”:

These were Russian soldiers equipped in mechanised battle armour. Curiously, like Colossus, the Rocket Reds were not depicted as enemies to be fought against by American superheroes. Instead, they were broadly depicted as altruistic, with one of their number even joining a version of DC Comics’ paramount (American) superhero team, the Justice League.

In 1987, a Russian superhero named Pozhar, portrayed sympathetically as a man unwilling to engage in needless violence, was caused by a nuclear explosion to merge with the American superhero Firestorm, in a story written by John Ostrander for DC Comics. This lead to Firestorm being essentially composed of both an American teenager and a Soviet superhero.

Within DC Comics, the Rocket Reds and the new Russian Firestorm are curious aberrations to the way in which Soviets generally were depicted up to that time. Creator Steve Englehart has never publicly commented on the driver behind the introduction of the Rocket Reds. We have contacted John Ostrander to ascertain why he introduced a Russian into the matrix of Firestorm’s fused personalities but have not to date received a response. In any event, during this time Mikhail Gorbachev had become premier of the Soviet Union and his book, “Perestroika” (“Restructuring”) in which he described his views on the reformation of Soviet society (popularising the word “glasnost”, meaning “openness”), was an unexpected commercial success in Western countries. As change was foreshadowed in the Soviet Union, despite US president Ronald Reagan’s fierce anti-Soviet rhetoric, the Rocket Reds were evidence of a mellowing of Western opinion about the Soviet Union.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1989, some Rocket Reds are shown in DC Comics’ titles as selling their suits, and others depicted as working for the Russian mafia, a reflection of the economic and political turmoil suffered in Russia at that time.

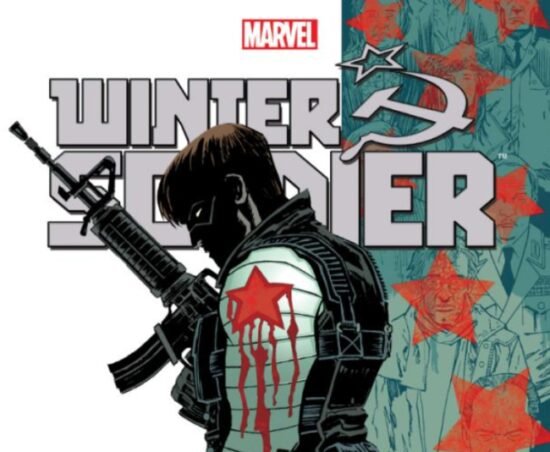

The Soviet Union was a convenient antagonist for patriotic American superheroes even after the cessation of its existence. One of those American superheros, the teen sidekick of Marvel Comics’ “Captain America”, was depicted to have died in a 1968 story, but in 2005 brought captured and subverted to become a Soviet assassin called “The Winter Soldier”:

The Winter Soldier was depicted as eventually breaking his Soviet indoctrination and even for a time replaced Captain America.

Stalin also remains an object of fascination for comic book writers. In DC Comics’ “Action Comics” (2015) #2, Stalin is replaced as ruler of the Soviet Union by arch-villain Lex Luthor:

And in Marvel Comics’ “What If…? Mirror Mirror” (2016) has Dr Rubion Richards and his comrades deployed by Stalin during the Cuban Missile Crisis:

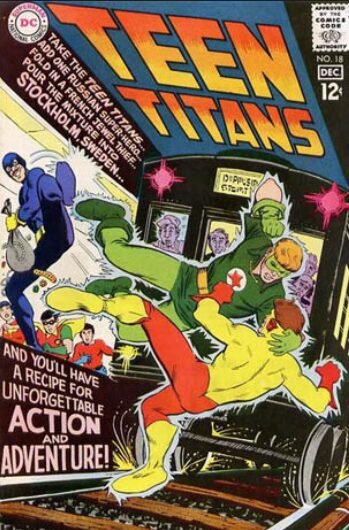

While it is overstating the position to say it is nuanced, other Russian characters have had roles as lukewarm antagonists to American superheroes. Below are Red Star, a character with not hostile but certainly ambivalent relations with DC Comics’ teen superhero group “The Teen Titans”, and a group of Russian superheroes called the Winter Guard, from Marvel Comics, who do not like Marvel Comics’ Avengers, but are not usually outright adversaries:

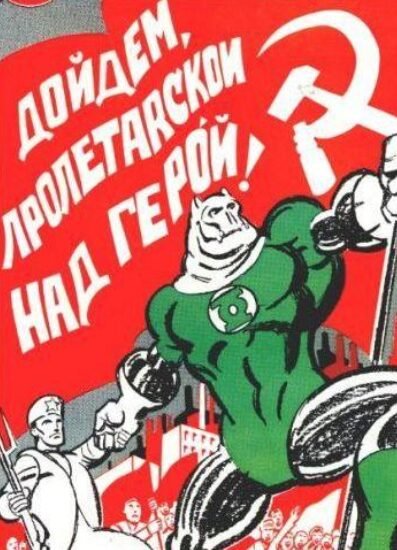

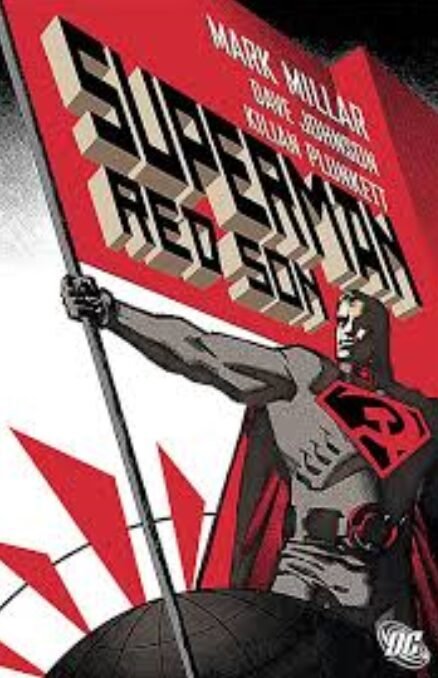

5. Russian iconography – Socialist Realism

But setting aside geopolitics as a parameter for the depiction of Russians in Western comic books, the striking visual Machine Age/industrial iconography of the genre of Soviet realism clearly appeals to creators. The visual attraction of this artistic style is ideally suited to comic books.

Below are images from Green Lantern Corps (1987), “Superman: Red Son” (2003) and “Black Widow” (2013), all depicting flag bearing exemplars of Soviet heroic art / socialist realism, and all notably bright crimson.

6. Russian women

The other attraction of Russians to at least American comic book creators appears to be centred around Russian women. Commentators have also considered how Russian women are stereotypically viewed in the West: “hypersexual, beautiful and dangerous creatures” https://russianuniverse.org/2013/10/14/russian-stereotypes/ or as “beautiful… under-dressed and promiscuous” http://theduran.com/western-racism-and-the-stereotyping-of-russians/ . This is very evident in how Russian women are portrayed in comic books, including the character Black Widow (see above). In American comic books, Russian women are exotic, dangerous, beautiful women who often wear tight and revealing clothing.

Below are a depiction of Black Widow, in what looks like a high gloss polymer body suit entirely inappropriate for a spy: covers from two of Image Comics’ recent publications “Baboushka” and “Red One”, each starring attractive female protagonists: and a panel from Image Comics’ “The Red Star” from 1999.

7. Russian Comic Books

Russia itself produces comic books, the themes of which are starkly different from the depiction of Russians in Western comic books.

This is a change from the Soviet era: Soviet ideology discouraged and occasionally banned comic books as a form of artistic expression http://www.kinokultura.com/2006/11-alaniz.shtml .

But in more recent times, Russian comics can be divided into three schools of expression: mainstream (for example, the children’s monthly “Nu, Pogodi!”); internet or WebKomiks (such as the manga series “Nika”), and ArtKomiks (intellectual expressions of comic art exhibited in art galleries). Below is a panel from “Nika”, clearly demonstrating its manga influences:

In 2009, Lebedev Studios released a comic book adaption of popular Russian science fiction novel “The Inhabited Island”:

Curiously, the text within the comic is in both Cyrillic and Japanese katakana, another nod to the influence of manga in Russian comic books:

In 2012, the Moscow Times was exuberant in its reporting of the establishment of News Media, a publisher of mainstream comic books which would essentially compete with the American comic book industry and thereby give rise to Russian superhero motion pictures. However circulation of each title is limited to print runs of ten thousand copies: slow selling titles by American and Japanese standards.

The titles include:

a. “Red Fury”, concerning a thief who is approached by an agency called MAK to find the Holy Grail.

This character seems to be a cross between Marvel Comics’ “Black Widow” (MAK is an obviously copy of Marvel Comics’ futuristic espionage agency SHIELD) and video-game-turned-comic-book character “Tomb Raider”.

b. “Meteroa”, a science fiction smuggler vaguely reminiscent of the character Ripley from the “Alien” motion picture franchise:

c. “Besoboi”, a mercenary who fights demons from Tskhinvali in South Ossetia. This character, with mystical tattoos, is vaguely reminiscent of the 1998 iteration of Marvel Comic’s “The Punisher” when re-cast as an avenging angel armed with mystical weapons:

Of all of the News Media titles, there is only one uniquely Russian concept, “Enoch”, featuring a time traveller who explores Russian history in a quest for atonement. The book includes many references to ancient Russian scripts.

And so we are left with this proposition: that while American comic books engage in across-the-board stereotyping of Russians, Russian comic books almost always copy American comic book concepts.