Matteo Book One: 1814-1915

EuroComics (IDW Publishing), November 2018

Writer: Jean-Pierre Gibrat

This beautiful comic is the English language translation of Matteo: Premiere Epoque published in 2012. It is concerned with the jealousy-fueled adventures of a Spanish refugee named Matteo Cortes, living as a farm labourer in the beautiful seaside town of Collioure on the French side of Catalonia. Those lucky enough to have spent time in Collioure, as your reviewer has, know that it is a pearl of fine food and wine. That visceral charge, the vibrancy of existence in such a fecund place, comes through in this equally rich comic.

Matteo is in love with the elusive Juliet, a beautiful French girl who snuggles up to Matteo in the hay fields but refuses to kiss him. Juliet speaks far too often about William, the son of the local landed gentry. William has studied wave mechanics in Scotland and when war breaks out with Germany, joins his fellow elite as a pilot.

France is besotted with the idea of war when it breaks out, but for Matteo’s mother, being Spanish is a winning lottery ticket. “For my father,” Matteo muses in a monologue, “patriotism reeked of death. He had nothing but contempt for it – and little love for the idea of borders. It was, nonetheless, my status as a foreigner that kept me out of the war, a paradox that delighted my mother.” Matteo’s French friend Pauly writes from the front, telling him not to be a “sap” and not to enlist. And Matteo himself broods, aware that his presence breeds jealousy and contempt from the anxious parents of the French boys who are fighting at the front.

Matteo’s father is dead, lost at sea, and all that was left is his small boat which washed up without him. Matteo’s father was a pacifist/anarchist who had to flee Spain after other anarchists killed King Alfonso XIII. This philosophical desire for peace means that Matteo’s father is wiser than the fathers of the French soldiers. “The Mayor began his family visits, informing parents of their sons’ heroic deaths without suffering, all in the line of duty. Each home feared his approach. When his hat moved past without the bell ringing, sighs of relief made the curtains tremble… every month he aged ten years, to the point of indifference, until it was his turn to learn of his own son’s death. Leaving him too lifeless to suffer the grief of others.”

Matteo eventually succumbs to community pressure and the quiet snubbing of Juliet, and enlists in the French army, to his mother’s horror. For her part, Juliet does not really seem to notice: she contemplates the birds flying like planes. As he boards the train, he meets his friend Pauly, who has blinded by gas. “Good luck old boy!” says Pauly. “Boy, you really are a sap!”

Matteo is witness to the horror of trench warfare. He sees men shot in the head, crucified on barbed wire, and blown up by cannon fire. “In the face of such a disaster, the order came… to retreat. Crawling from one shell hole to another like a whipped dog, I slid into the trench, away from that grisly site filled with the rubble of men.”

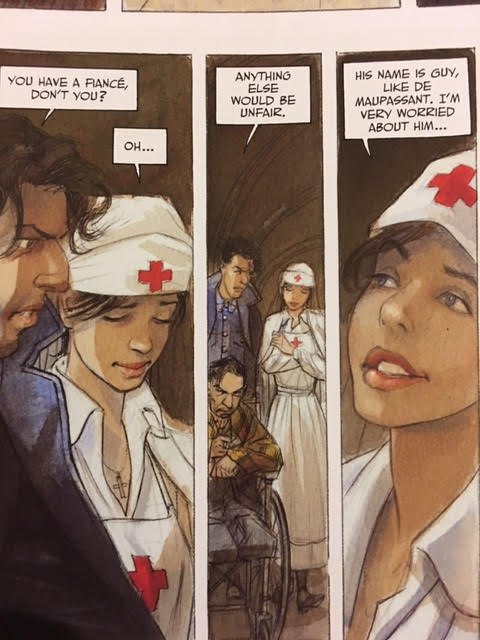

Matteo is inevitably injured himself and finds himself in a hospital. There he meets a charming and beautiful nurse named Amelie, who teases him over his Southern French accent. Amelie frets over her boyfriend who is on a battlefield in Argonne. Amelie and Matteo share that curiously honest “but for” relationship in which people who are mutually attracted, but who are already in relationships, sometimes indulge.

Matteo is thus exposed to a new type of horror of war: the dripping slow deaths of the hospitalised. Matteo’s vain friend from the trenches, named Berluchon, who once fussed over his stylish moustache, shoots himself rather than go through the rest of his life with his face a mass of scars. Amputees litter the courtyard. Amelie cries in the night, and smiles during the day to bring some happiness to the suffering.

Matteo returns to Collioure on leave and finds that Juliet is now in a relationship with William. An encounter at a local tavern reveals William as a bourgeois weakling. The day before he is to be redeployed, Matteo and Juliet have a final interaction made turgid when Matteo’s venomous spite mixes with Juliet’s guilt.

Matteo then drinks himself into oblivion. While he is asleep, Matteo’s mother and the blind Pauly pile Matteo into his father’s boat and row him to Spain, beyond the reach of the war. Matteo’s mother stands at the prow like a figurehead, an image of proud Juno, and as the boat approaches the Spanish shoreline Pauly mocks Matteo again for being a sap. The boat which killed Matteo’s father en route from Spain to France saves Matteo by taking him from France to Spain.

Before being shanghaied by his own mother, Matteo speaks of the horrors of war to a group of wives at a church, and then contemplates what he has done: “My mother hoped to transform the discontent I was sowing into a holy pacifist rage. I did not share her optimism and left the chapel shamefaced at having drowned their last hopes, at having already dressed the future widows in black.” It is perfectly written, an envy to those who indulge in literature. For in truth the beauty of this book is not the startlingly clean and elegant art. The true beauty rests in the text. And the remarkable thing to that is that this title features the English translation. “Translation is like a woman. If it is beautiful, it is not faithful. If it is faithful, it is most certainly not beautiful,” is a quote attributed to Yevgeny Yevtushenko. This assessment is laconic and horribly sexist, but for translation it is true. This translation is unabashedly beautiful.