Any review of The Wicked + The Divine (Image Comics, 2014) and its first collected work, entitled The Faust Act, needs to first address the influence of Jack Kirby in comics.

Jack Kirby was a masterful writer and artist responsible for the creation or co-creation of many immediately recognisable comic book properties, primarily for Marvel Comics, including the X-men, the Hulk, Captain America, and many others. In 1970 Kirby moved from Marvel Comics to its longtime rival DC Comics. During his four year stint with DC, Kirby created a pantheon of science fiction gods: cosmic beings representing various archetypes, all viewed through a decidedly 70s hallucinogenic prism. Evidence of this includes an abundance of abstract and psychedelic geometric forms in the art, together with bubbling manifestations of unearthly energy; satanic villains carved from granite with deadly, glowing crimson eyes; and the godlike but decidedly hippie Forever People with names like Mark Moonrider and Beautiful Dreamer. Contemporary flower-power influences define and guide Kirby’s creative output during this period.

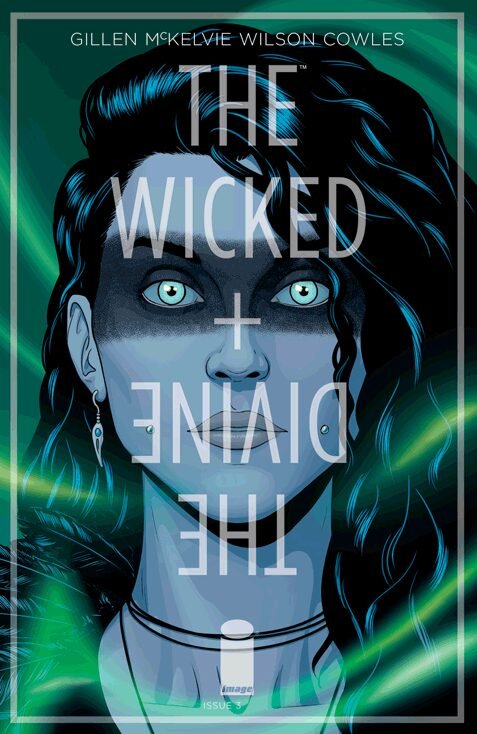

If Kirby had moved from Marvel to Image Comics in 2014 instead of to DC Comics in 1970, he might have collaborated with Kieron Gillen and Jamie McKelvie on The Wicked + The Divine (Image Comics, 2014). The work features the same integration of current pop themes into mythological figures and archetypes. Instead of flower power as the blueprint, the work explores the contemporary obsession with the famous. We can see French techno musicians Daft Punk very plainly in a character, grim Scandinavian god Wotan: the effervescent and personable Florence from Florence and the Machine in Japanese sun goddess Amaterasu: temperamental pop singer Rihanna in North African goddess Sakhmet. With others, the characters constitute a group called the Pantheon. And they are each singers and stage performers, drawing obsessive adoration as both pop stars and as gods.

One of the overarching premises of the story is that these characters are reincarnated every ninety or so years in an event called The Recurrence. A prologue flashback to 1927 features the group suicide of four of the characters, the others having died and being reduced to skulls arrayed around the Pantheon’s table. In the flashback, Susanoo, a Japanese god of thunder, strikes a pose and in a singular frame (skilfully rendered by artist McKelvie) conveys the ethnic supremacy underpinning the culture of 1920s Imperial Japan. But with the gods’ reincarnation in 2014, he is Baal, a god of lightning, black and lordly, imbued with the arrogance and indifference of rapper Kanye West.

The immediate protagonist, Lucifer, is a woman in a white suit with the charming and impetuous personality of the devil archetype. The text itself makes reference to this character giving a nod to David Bowie (Bowie’s Thin White Duke phase of stagecraft). But perhaps the more obvious source material is the androgynous Annie Lennox or Grace Jones. Lucifer is wilful, devious, engaging, and does not care much about rules.

The other lead character is an ordinary girl named Laura, a resourceful English fan who is picked out of a concert crowd by Lucifer for reasons still not obvious. She is a pretty girl of mixed ethnicity and entirely ordinary, a student enacting the university pantomime of petty rebellion against her well-meaning parents, not caring about her studies, immersed in the pop culture of the Pantheon.

Linking contemporary musicians to gods or godly archetypes, some obscure and some obvious, is not new but it is clever. It provides two levels of accessibility to the characters, one being through the frame of pop culture, and the other through myth. Even though the story, at least as first, does not reveal much about each of the characters, the reader almost immediately knows a lot about most of them.

Within the first chapter, the story becomes a murder mystery. Lucifer is in an English court facing an irate judge (echoing both an actual 1971 US court case brought against Satan, and a 2011 film with a similar concept). Here, the devil is being judged in a mortal court, and she is plainly amused. Lucifer has killed two would-be assassins by snapping her fingers, and she baits the judge with the impossibility of that. She teases the judge by threatening to do it again. As her thumb snaps on her fingers, the judge’s head explodes. Lucifer is clearly baffled and surprised. She voices her innocence. Has Lucifer been framed by one of her contemporaries? In this first volume, Laura’s quest to learn the truth of the murder, meeting the immortal suspects, is the mechanism by which we meet each of the reincarnated entities and learn the pecking order.

The story is appealing for any number of reasons. The violence of the murders, the constant references to the insatiable sexuality (and bisexuality) of the gods, Lucifer’s snide rebellion against authority reaching a crescendo in her jail break (a display of awesome and unstoppable power juxtaposed with the casual nonchalance of a takeaway coffee, a cigarette and an iPod), each tick many boxes of popular appeal. The murder mystery is baffling and engaging. The way in which the Pantheon are policed in their excesses indicates ancient and unrevealed rites and rules. The depth of the backstories of the gods provide plenty of fodder for those wanting to read outside of the text. And the art is clean and beautiful, with meticulous focus on facial expression.

Archetypes as protagonists is not a new concept (see most notably Julian May’s Many-Colored Land series of books) and neither is the idea of human avatars for gods (Piers Anthony 1983 novel “On a Pale Horse” and its sequels, and even the initial concept behind Marvel Comics’ Thor envisaged Donald Blake as merely an avatar for the god of thunder). But the twist here is that the gods are on an egg-timer existence. We are told that the Pantheon’s cohort lasts only two years before almost all of them burn out and die. Their shining and glorious existences, like those of many pop stars, is ephemeral.

Worse for the characters, premature attrition seems inevitable. The flashback at the beginning of this first volume, with the eight skulls of the gods arrayed in front of empty seats and the final four engaging in a ritual of group suicide, indicates the immortal characters face grim destinies before their time is done. Do they remember their past lives? It seems that the characters do not learn from their mistakes upon being reincarnated, evidenced by their high public profiles and visible excesses. As archetypes, they each will inevitably be true to form and are unlikely to change or grow as the series progresses. That is probably left to Laura, who by the end of first volume makes a discovery about herself which is either going to be euphoric or catastrophic. Or, given the high level of craftmanship exhibited in this comic books so far, possibly both.