Writer: Neil Gaiman

Art: Mark Buckingham

Marvel Comics, December 2022

English author Aldrous Huxley wrote the acclaimed dystopian novel Brave New World in 1931. Brave New World is a grim of all visions of the future. Social engineering, eugenics, sexless procreation, and state-sponsored drug-induced bliss are all indicia of the global society of the year 2540.

While there are several key characters in that novel, the two most important (in this critic’s view) are John the Savage and Mustapha Mond. John was born outside the system, in a Native Indian reservation in North America, where he learned to read through the works of William Shakespeare. Shakespearean notions of morality shape his worldview. Mond on the other hand is a pillar of the system: he is responsible for the governance of Western Europe. Mond is at the top of the tree: he is an Alpha Plus, at the very pinnacle of society. He has read the banned books, and knows precisely what humanity has left behind to achieve a completely peaceful, orderly world. Yet Mond is hardly some sort of supervillain. He is thoughtful, good-natured, and hyper-rational.

Around thirty years before Brave New World, the father of Anglophone science fiction, American writer H.G. Wells, published The Sleeper Awakes. In this novel, an Englishman named Graham awakes from a coma 203 years in the future. Graham discovers he is a celebrity, and that his aggregated wealth is enormous. The year 2100 is a plutocracy, where the lower-class inhabitants live in drudgery, and are dressed in coloured uniforms denoting their basement status and the categorisation of their contribution to society. The story follows both Graham and a band of rebels who overthrow the ruling White Council, but who in turn are corrupt.

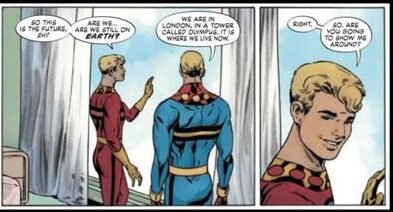

What have two novels, one 91 years old and the other 123 years old, got to do with Neil Gaiman and Mark Buckingham’s new literary morsel, Miracleman: The Silver Age? Everything. In this title, Graham / John’s role as the outsider – or, almost literally, the sleeper – is filled by Dickie Dauntless, otherwise known as Young Miracleman. Dickie is perhaps 14. He has been improbably brought back from death by his mentor, Miracleman, using alien technology. Decades have gone by since Dickie’s passing.

Dickie is almost immediately confronted by social mores he does not understand and finds offensive, mirroring John’s bafflement in Brave New World. Dickie is introduced to aliens and people dressed in what Dickie regards as an inappropriate fashion. Miracleman himself, like Mustapha Mond, rationally and reasonably decided that peace and stability are better than freedom and democracy. Dickie gets a strong whiff of that viewpoint when Miracleman describes democracy as a lost fad, and that he is now in charge of humanity.

Miracleman, despite his warm smile at seeing his long-lost friend, is to us more menacing than Mustapha Mond. Mond is after all merely a human who has formed a reasonable (if, to those of us who adhere to the notions underpinning liberal democracy, repellent) view on what is best for humanity. Miracleman however is post-human, and the societal parameters he has established in his new world are not immediately obvious. Miracleman has a consort, not a wife (there is a very vague suggestion that the offer of her “counsel” of Dickie might be sexual), and Miracleman has a daughter who appears to be very young but says she is 21: she floats unclothed inside Dickie’s bedroom. The bedroom is designed to look like it belonged to a boy growing up in 1950s Britain, so as to give Dickie comfort and familiarity. That illusion very quickly blackens and burns.

On the art of Mr Buckingham: Tyrants build monuments to themselves which are grand in scale, but which historically are massive buildings, solid and symmetrical, such as the Pyramids at Giza, Hadrian’s Tomb in Rome, or even Benito Mussolini’s Central Train Station in Milan. (In science fiction, we otherwise have the throne room of Leto II in God-Emperor of Dune, deliberately designed to intimidate those who approach the ruler of the universe.) And fascists have historically abjured abstract modernism as decadent: simple monoliths convey power. But Miracleman’s headquarters is fantastical, difficult to comprehend. It is a miasma of Fascist heroic statues, images of past challenges, and a colossal nude. Art reflects society, and what society is recognisable to Dickie (or to us) in this? It is a striking panel by Mr Buckingham, immediately communicating to the reader that mere mortals cannot grasp the concepts underpinning this new world. But otherwise, the art (and some of the dialogue) is a very deliberate re-rendering of Miracleman #23 (published in June 1992 by Eclipse Comics).

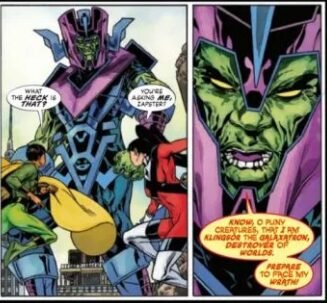

Dickie tries to maintain his composure but, retreating back in his room, he crumbles, calling out in tears for his long dead mother. Dickie is unaware that other eyes watch the spectacle of his awakening, uncaring of both his privacy and his shock. Those elite of Miracleman’s world, like the Alphas of Brave New World, enjoy special privileges. They are inevitably super-powered, and so play by engaging in mock battles strewing destruction. Three of them hurl each other through vintage buildings such as the World Trade Center twin towers (9/11 did not happen on Miracleman’s watch, nods Mr Gaiman) and the Chrysler Building. One of the elite, Kay, notes she would like to have sex with Dickie, perhaps fulfilling the role of Lenina in Brave New World.

In this first issue, Mr Gaiman and Mr Buckingham quickly bring to boil fin de siècle uncertainty. We as readers are now no longer in a millennial phase of Western history with all of its hang-ups about what is next in our future, and it therefore is no coincidence that this story is set in 2003, not 2022. Setting aside what has been reanimated from Miracleman #23, the borrowings from Brave New World and The Sleeper Awakes are almost repetitive: even the dating system, calculated from the date of Miracleman’s assumption of power, mimics the dating system of Brave New World (calculated with reference to the generally acknowledged inventor of assembly line manufacturing, Henry Ford). For those across fin de siècle literature, this title is an exercise in sweeping up the abattoir floor to make a pie. We know the recipe. Where is the finesse?

The only question is whether or not Dickie will be a revolutionary like Graham, whether Miracleman will realise his mistake and set it right by killing Dickie, or whether Dickie in desperation and horror will seek John’s fate:

“Slowly, very slowly, like two unhurried compass needles, the feet turned towards the right; north, north-east, east, south-east, south, south-south-west; then paused, and, after a few seconds, turned as unhurriedly back towards the left. South-south-west, south, south-east, east.”