Writer: John Ridley

Artists: Giuseppe Camuncoli and Andrea Cucchi

DC Comics, November 2020

At the very beginning, I did not think The Other History of the DC Universe would be a comic for me. I do not usually enjoy comic-books that rely only in narrative to tell their story and don’t have any actual speech bubbles, except for the rare exception (books like the poetic Dr Strange: Into Shamballa and Moore’s beautifully written Saga of the Swamp Thing #60). So, when I opened issue one, I thought, “Oh great, it’s one of those books”.

Except it is so much more than that. Many superhero comic-books have attempted to rediscover or recontextualize a character from the point of view of their status as a minority. But very few succeed in the same way this first issue does, and the reason is very simple: John Ridley, the writer, is a black person, and many of the ideas he explores in this book could very well come from personal experience.

Website EW https://ew.com/books/john-ridley-the-other-history-of-the-dc-universe/ notes:

The 1986 comic book series History of the DC Universe left a powerful impression on 12 Years a Slave screenwriter John Ridley. A stunning mix of prose and art, the two-parter is a chronology of DC’s entire fictional world, explaining what was canon following the groundbreaking crossover event Crisis on Infinite Earths, which forever altered DC’s continuity. “I loved it because it treated the characters, and overall DC universe, as a real timeline,” says Ridley, who previously wrote The American Way. “As if it were history, and not just people sitting around musing about these characters month to month.”

However, as a Black man, Ridley also noticed the series’ shortcomings — specifically, the marginalization of minority characters. And 34 years later, he is giving voice to those silent avengers with his own collection, aptly named The Other History of the DC Universe (out Nov. 24).

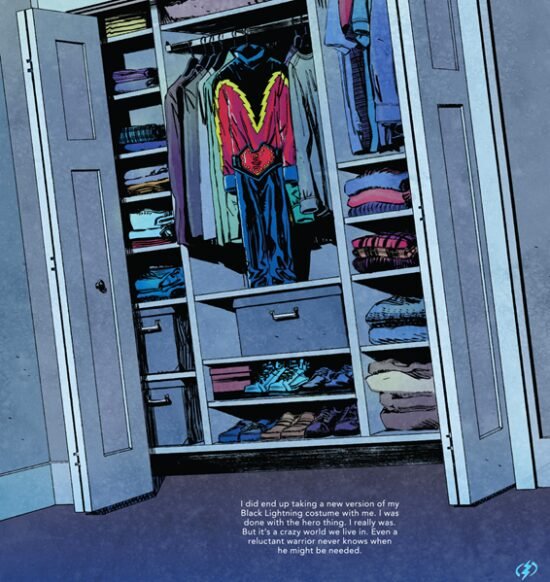

The first issue of this anthology series does not focus on taking down bad guys or stopping some kind of intergalactic threat. Instead, it depicts many of the events that led to the creation of the modern DC universe (DC Comics, an American comic book company, is the publisher of this title) as seen from the perspective of Jefferson Pierce, who would become a superhero called Black Lightning.

This dialogue-less comic, who is told entirely from Pierce’s point of view in squared narration boxes, would not be as enjoyable as it is without the beautiful artwork by Giuseppe Camuncoli and Andrea Cucchi, who make every panel worth taking a good look at before diving into the next page.

Jose Villarubia’s colors add another layer to their artworks, as the use of color to express different types of moods (usually sadness and loneliness, both of which Pierce experiences a lot). This elevates the book’s visual aspect, while still being faithful to classic superhero comics by having vibrant colors decorate the suits of the many costumed adventures who show up in this book.

It is through Pierce’s cynical worldview that we get the best critiques to comic-book culture in the 70s, especially focused on race-related issues. His gold medal in the 1972 Olympics does not provide him the fame and fortune most white athletes got for the same honor. This parallels how later in life he and other black superheroes would be overshadowed by the more well-known and accepted white heroes.

It is with small concepts like these that the book manages to intertwine the two stories, one of institutional racism and one of the fictional rise of superheroes in the DC Universe. It is through this interweaving of a real and a fictional story that the book managed to catch my attention, as it is a trope very compelling.

The first half of the issue focuses on Pierce growing up, settling down and becoming a teacher. It explores the many incidents that made him into the man he is once he finally puts on the suit. Save for radical comic titles such as Denny O’Neal and Neal Adams’ Green Lantern / Green Arrow, it would have been very difficult to discuss in the context of superhero comics themes like underage crime, toxic masculinity and hate crimes back in the 1970s, when Black Lightning first made his debut in comics. Today however not only can a writer explore how these issues helped shape our main character into a costumed hero, but do so in a way that feels extremely relevant.

Pierce as a teacher is much more interesting than Pierce as a superhero, especially considering the context around him and how he fights to reduce crime and school abandonment in his black community. Pierce teaches his children how to be better people, as any teacher should do.

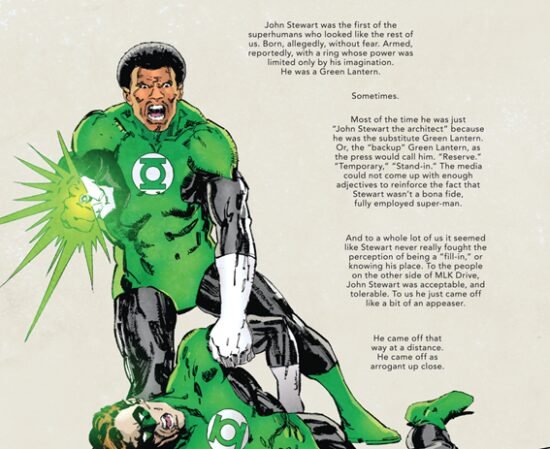

One of the things that I most enjoy about the depiction of superheroes in this book is how the Justice League is first introduced as an exclusive club of white people who fight crime together. The Justice League is DC Comics’ foremost banding together of its superhero characters. Even when a black superhero finally shows up, he is “just” a backup Green Lantern. Pierce does clearly not like the Justice League, and his reaction to the first black superhero is interesting in many ways. John Stewart (the reserve Green Lantern) represents the change Stewart wants to see in the world. But Stewart is also a part of a group that stands against everything he believes, a group he even rejects when they try to take him in, as he insists that it’s a mere act of tokenism. Stewart is always the “secondary” Green Lantern, and Pierce blames him for not trying to be anything more than that.

Once Pierce does become Black Lightning, he patrols the streets of crime-ridden Suicide Slum, an inner city suburb of the fictional city of Metropolis, to ensure they’re safe enough for his wife, his children and everyone else. Metropolis is famously the home of DC Comics’ premier superhero character, Superman. Pierce confronts Superman about the “big superheroes” and their refusal to take action against the small crimes of places like the slum.

This book also brings up something a lot of people do not really think about when reading about Superman, however: despite not approving of his morals, Pierce empathizes with him on a different level, as Superman, an alien, understands what it means to be part a minority. Of course, Superman looks and acts like a perfectly normal white person, and this does not mean he is without privilege. But Superman is an alien from a destroyed planet, and even though he may look human, there is a hole in his chest that cannot be filled. This is why Pierce feels happy for Superman once Supergirl reveals herself (after a period, in continuity, of being hidden from public awareness), giving Superman a form of hope that he finds himself unable to encounter during his long nights as a costumed vigilante.

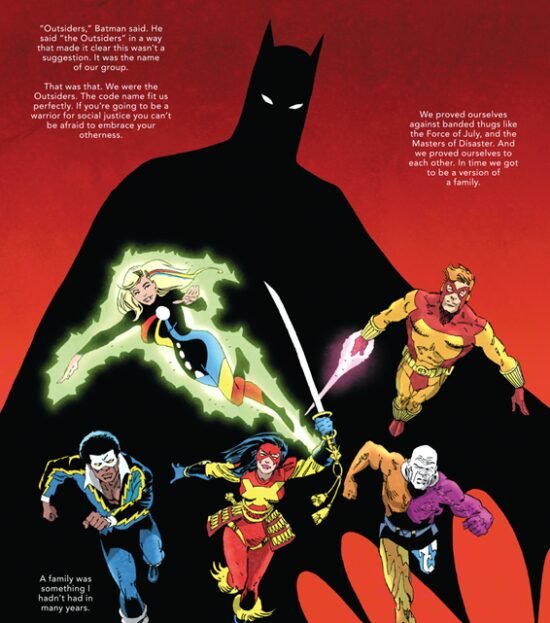

This book is not afraid to challenge the ideas presented by the main icons of the DC universe. Not even DC Comics’ most formidable character, Batman, is exempt from criticism. Pierce nonetheless ends up joining Batman’s team of Outsiders, an ironic title if we consider the events in this book and how Pierce felt at the time. The line, “If you’re going to be a warrior for social justice, you can’t be afraid to embrace your otherness” especially resonated with me in the intersection of justice and diversity.

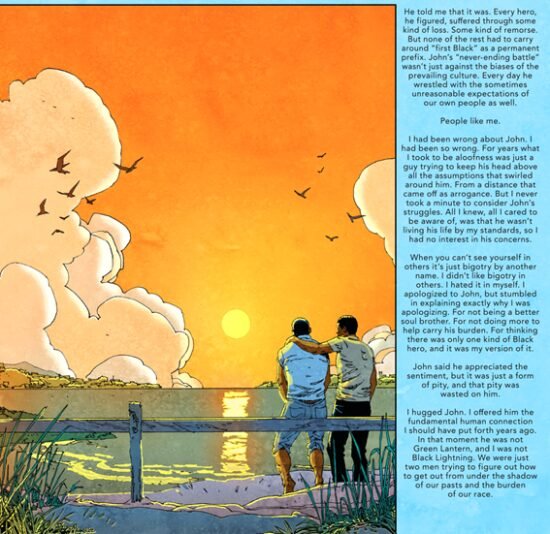

The character development is subtle, but very interesting. Not only does Pierce end up meeting Stewart face-to-face, he also learns enough about him to understand that his original view of the “backup” Green Lantern was wrong. Mr Ridley reveals that Stewart was doing what needed to be done to be able to impart justice, even though he didn’t agree in full with the Justice League’s methods. Pierce understands that although the system is flawed, Stewart was not willingly a part of it. This is a very powerful message that is very likely written from experience: it is very easy for people inside a minority group to turn against each other instead of focusing on the main issues they all have to face.

Pierce also has to overcome some serious personality flaws that the book clearly notes. Pierce, for example, scolds a sensible kid for not being “man” enough and allowing others to bully him. The child grows to be successful later in life, making Pierce feel embarrassed about his own over-masculine approach to teaching. Pierce’s wife divorces him for his lack of trust in her, and both of these issues are described as deeply rooted in the way society had so far treated Pierce as a black person. Pierce’s personality traits in this regard are a defense mechanism designed to get him through life, to survive an unfair and ungrateful world.

This book does not try to demonize DC Comics for not trying hard enough to represent racial issues during the 1970s. But it does address the fact that many of these explorations were made through the eyes of white people (the late Mr O’Neal and Mr Adams are white), for white people, to make them feel better about their own whiteness. This issue will be much more relatable to black people than those old comics. Mr Ridley’s critical involvement emphasizes the importance of books written by actual members of the minority they are trying to represent.

One thing was clear to me once I finished reading The Other History of the DC Universe#1: we need more superhero books like this one. Instead of relying on tired old tropes and predictable retcons to continuously add more and more lore to a character’s history, it looks back to see what our contemporary worldview can add to the reading of these classic characters. Here, the story is told from the point of view of an important minority creator, enabling him to recount his own struggles.