Writer: Inverna Lockpez

Artists: Dean Haspiel, José Villarrubia

Vertigo Comics, September 2010

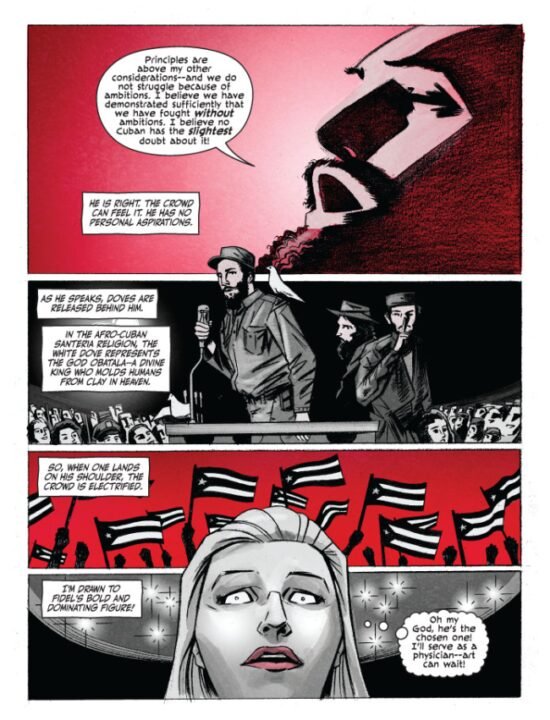

2010 WAS EVIDENTLY a good year for a generation mature enough by then to tell their personal stories from around the world in graphic formats with an unusual skill and grace. The nice hardbound edition of CUBA MY REVOLUTION attracted me first by its sleek appearance, with a sketch of author Inverna Lockpez or her double on the cover in a typical pose for a new-world worker, iconographic in communist art, eyes upward gazing into the future, tool in hand. The prospect looks inspiring, except for the shadow of a jail cell in one corner, fists gripping the bars.

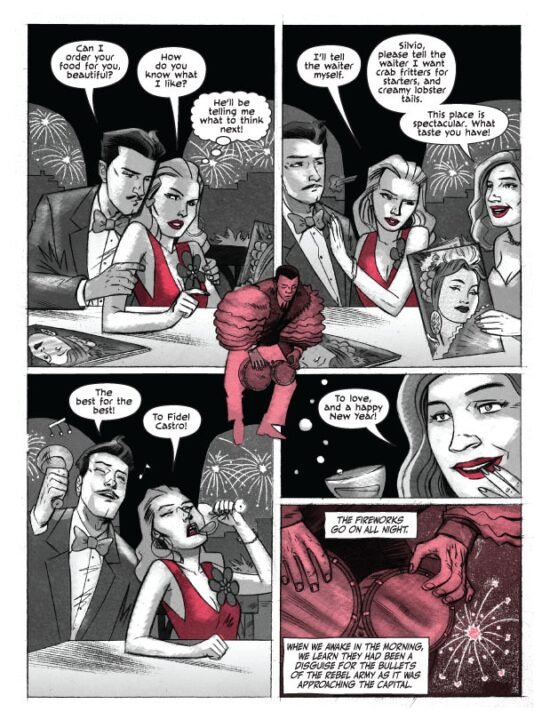

Heroine alter-ego Sonya makes her debut, age 17, on page one in a scarlet cocktail dress in the foyer of a chic Havana apartment, eager to go out to celebrate New Year’s Eve on December 31, 1958. We learn as she taps her foot impatiently waiting for mom, that dad in the background reading a newspaper is a respected doctor, and we get a hint that maybe she is a spoiled brat as we see so often in feel-good dramas where the young person eventually converts to a winning attitude. Yet I was convinced from the start and throughout that this is an honest account of real events, not turned by art into an action drama, nor by sympathy into propaganda for one side or the other.

For there are two sides at war here from the beginning. The reader steps inside history in the body of a single young woman trying to make sense of it all: for herself, her family, and the people and land around her.

The detail that stuck with me that first night out partying, something only someone there could notice, is Sonya’s remark after the clock struck midnight that the fireworks go on all night.

“When we awake in the morning, we learn they had been a disguise for the bullets of the rebel army as it was approaching the capital.”

The unloved dictator of the island fled with friends and family.

Sonya’s story covers the early years of a war that has endured from that night to the present between the Cuban people and their former colonial masters who were dispossessed. In three fifty-page parts, we see a good deal of action and movement to multiple locations. Sonya goes to classes, talks to neighbors, has a boyfriend. The chic family apartment and dad’s office remain safe havens amidst revolutionary social changes.

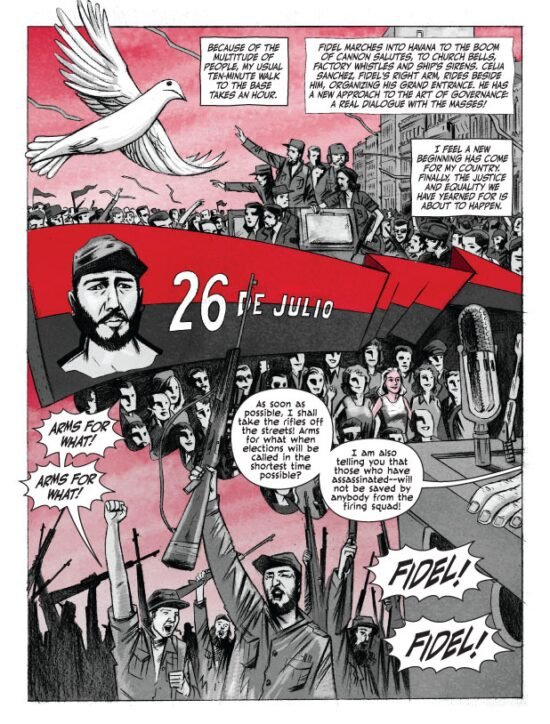

The artwork by Dean Haspiel makes daily life dramatic enough without hyperbole. Depths of gray-toned surfaces elaborate interiors and distinguish figures so well I did not notice on first reading the book is not in color nor in black and white. Flat red splashed on the title page by colorist José Villarrubia melts into the background inside, and slips across the pages in snatches and eddies with beautiful restraint. The shades of black and gray in the illustrations refract the bits of red and seem like real colors.

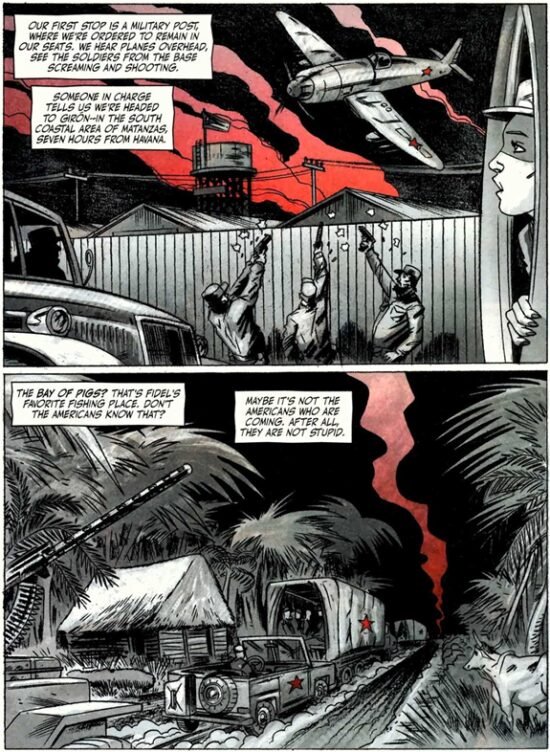

Sonya wants to be an artist, but mom wants her to be a doctor, like dad. She joins the people’s militia and becomes a medical assistant. She marches and trains. In 1961, when the US-backed invasion of Cuba at the Bay of Pigs is launched, she moves to the front, where a brigade of Cuban militia was already massacred by the invaders. Her first night in the field she sleeps among stacks of dead bodies.

Seeing soldiers shooting pistols at a fighter plane with false-flag markings freshly painted by the US Central Intelligence Agency to look like a Cuban aircraft is a nice touch. Prop-driven fighter planes in the 1950s were vulnerable to gunfire as reported by pilots in Korea a few years earlier, who found it terrifying strafing army positions, because rather than run for cover, the troops would stand up and shoot as they do here. False-flag markings left room for plausible deniability. The USA did not want the world to know it declared war on Cuba, so it bombed and invaded in secret, using Cuban exiles and deception.

As it happens, one of the exiles lured by the CIA and sent back after training in Guatemala was an old boyfriend of Sonya’s, whom she discovers afterward while attending the wounded. One more hope closed.

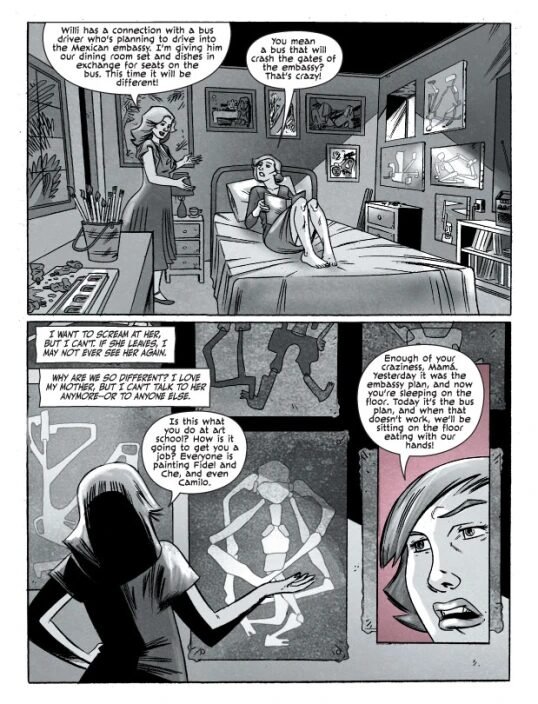

Sonya later becomes an artist, a good mural painter, though she is forced into a conventionally approved realist style to uplift the people. She chafes at the imposed convention that curbs her desire to express herself as she would like, though strict conventions curbed artists in 1950s America, too, and today, if that’s the only point.

When she eventually leaves to join mom in Miami, Sonya feels immense relief to escape the war zone. It feels like freedom.

Fifty-five years later, we can judge the sequel. Unlike the black flower-seller Sonya knows in Havana who is unhappy with the prospects for his street trade, people of black and mixed races in Cuba generally, about one-third of the population, reached relative parity by the 1980s in work, education, and health status. The achievement is unmatched anywhere else. Affirmative action worked by suppressing discussion of race issues and raising up everybody at once.

Vigorous medical development and massive public health measures—better sanitation, housing, roads, education, diet—has resulted in Cuba having equal and sometimes far better rates in key health indicators than wealthy countries. Despite the country’s poverty, expanded public space, goods, and services has resulted in typical causes of death looking more like the middle class in wealthy countries than poor people.

By 2009, access to education and the literacy rate in Cuba reached nearly 100 percent, ranking tenth of 125 countries. In addition, student achievement has been noticeably higher than in other Latin American countries like Chile or Brazil, attributed to better child health, housing, and family support. Stable work and living situations assist enduring relationships with students, teachers, and the community.

Upward mobility in Cuba was facilitated by most upper-income professionals leaving the island, like many of Sonya’s friends and family, and finally Sonya herself. The exodus, rather than debilitating the economy, opened opportunities for others, with assistance from the government to assure equal access.

A news item from 2006 that emerged in my search for details about Cuba illuminates the most scarring episode in Sonya’s story. In the aftermath of the invasion, in her role as a medical practitioner, she had forced her way past guards into a locked room to tend to a screaming man with a mortal wound, who turned out to be a CIA agent. She was abruptly imprisoned and interrogated severely.

In the news item, originally from a French source, five Cubans were arrested in Miami, supposedly for espionage, but they were actually there, as came out in the trial, to monitor a network of terrorists drawn from the Cuban exile community in Florida, supported by the US government for over forty years. The terror network was involved in bombings and sabotage intended to destabilize Cuba and discourage foreign investment and tourism, resulting in significant casualties and property damage, including the bombing of a Cuban airliner in 1976 that killed all 76 persons on board. Violence escalated in the 1990s and 2000s.

It is evident strict security in Cuba has mostly been a response to prevent terrorism as well as assassination efforts by agents of the CIA and friends. Fragments of this layer of reality rumble in the background of Sonya’s story in real time, surfacing in her experiences and conversations.

In her case, one can suppose an officer ordered no contact with the imprisoned CIA agent to control the circle of suspicion. Following her forced entry, the resulting episode of harsh treatment looks like overzealous paranoia by her jailers, yet their purpose to prevent terrorism softens the judgment once one learns as they would know, the stories of victims of attacks who might have been spared by increased vigilance. For Sonya, though, from then onwards she cannot shake off being terrified of the police.

Different sides of the Cuban story, for and against the new revolutionized society, swirl around Sonya’s life and thoughts. The parts balance into a whole representing her one, genuine point of view. Whatever side one imagines is the important one to take, this one from her counts.

*

NB. Thanks for facts from the JFK Library on the Bay of Pigs; D.R. McLaren 1999 on Mustangs over Korea; J. Meerman 2001, and Confronting Poverty 2022 on low-status minority mobility; S.M. Borroto Gutiérrez et al. 2003, and Cooper et al. 2003 on health; Y. Murtala Akanbi et al. 2003 on literacy; J. Marshall 2008 on academic advantage; L. Weinglass 2006, and R.S. Dunn 2022 on US-backed terrorists; and to Sonya for sharing her memories.