The Wicked + the Divine: Mothering Invention (volume 7)

Image Comics, October 2018

Writer: Kieron Gillen

The Wicked + The Divine is a unique comic. It takes concepts of resurrection and divinity and mixes them with contemporary pop culture. The overarching plot runs like this: Throughout human history, god-like archetypes suddenly appear every ninety years or so, but are all destined to die within the following two years. We like most of these eccentric characters, and each of their deaths are both bitter and shocking.

Murder across aeons

The story, for the most part, has dealt with the most recent batch of avatars, with infrequent flashbacks to the previous iteration of the 1920s.

That temporal parameter dramatically changes in this volume. We witness, by panel, page after page after page of startling, repeated visions of death and decapitation by magical explosion. Each panel is dated, stretching back thousands upon thousands of years, in various cradles of civilisation- the African savannah, ancient Egypt, ancient Japan, ancient northern China, Mesopotamia, Mayan America, ancient Australia, and so on.

Each murder or attempted murder is captured in a single panel snapshot, the same murderer killing the same victim, usually successfully, rarely unsuccessfully, most often in a sneak attack from behind.

Jumping forward to 2016, as the story progresses, each of the current crop of characters, like their predecessors for untold generations, are being picked off. In this volume, only one of the characters is killed: The Morrigan, a manifestation of a three-phased death goddess.

The series of deaths, as stated above, started off as a highly engaging concept. In this story, divinity does not ordinarily mean immortality, other than on a long recurring arc. Each characters’ deaths was often surprising and apparently irrevocable because most of them had their heads blown off. There was a grim deathwatch in place: who would be next?

This volume gives the foreground whodunnit mystery an immense depth of history. The question is redefined from who is responsible for the deaths of the pantheon of protagonists, to instead why thousands of years of murders have occurred.

The heads in the cellar

But over the past year or thereabouts, the story has, in its efforts to be unpredictable, strayed from this fundamental premise. The villain, Ananke, has lined up in a crypt the living heads of three of the dead gods, sans bodies, who all seem to be rather surprised that they are there. We are a little surprised, too, and disappointed. We get the sense that writer Kieron Gillen has brought back some of the popular characters on public demand: that he has fallen victim to that worst of the American superhero traditions, the impermanent death.

The three “dead” characters who have reappeared are:

a. Lucifer, a charming, sinister, androgynous protagonist with hellish powers, whose death was a genuine shock early in the story;

b. Tara, an archetype of sexual desire and adoration, hated when she did not give her admirers what they wanted, and probably the most likeable of all of the characters in the series. Tara suicided as a consequence of being depressed from who she was. Tara had the least time of all of the avatars in the series, but in our view had the strongest and most clearly thought through character traits of them all; and

c. Inanna, a likeable avatar who bears an uncanny resemblance to the pop star Prince.

In a rather gruesome development in this volume, the lips of each of the heads are sewn together. The distress of the characters is clearly visible in their facial expressions.

The explanation for the deaths and resurrections of the godlings, proffered in this volume, is that there is a sort of ancient curse between two warring sisters (one of whom is Ananke). The two sisters are sorcerers. One lays injured and exhausted on a desert floor, and the other looms overhead, splattered with blood, wearing the helm made of the skull of a horned animal. They play a game of spells. The word “mystification” refers to the art of twisting a concept into something unintelligible. We see mystification clearly in play here between the two characters – we do not really understand what is going on, in an annoying way. Finally, a stone knife dips, and the exhausted sister dies horribly.

The Golden Bough

All of this seems contrived, and, if actually necessary, a few years too late. In our view, the phenomenon of the appearance of the avatars did not really require an oddball explanation grounded in Stone Age times. It instead could have been as inevitable as periodic ice ages, a seasonal occurrence which occurs for incomprehensible reasons as essential as the tilt of the Earth (much like the premise of the motion picture Highlander).

By way of this current volume, we perceive that Mr Gillen is engaging in a backfilling exercise in respect of the story. There is no sense that the explanation as to why the faux-gods appear, only to be all doomed, has been rolled out in a measured way. It has been knocked into our vision, a seemingly late effort to tie everything together. There is a sense that the series has lost its way.

But here we are. Ananke has killed her nameless sister in the desert using a knife, and they have engaged in a duel of wits or perhaps spells which create the mechanism of the periodic incarnations. Notably there is nothing flashy in the process of the establishment of the pantheon, in marked contrast to the psychedelic magic of the major characters.

We expect that this explains why various cultures throughout the world have traditions of thunder gods, underworld gods, trickster gods, a goddess of love, a god of dance, a goddess of the hunt, and so on. In that sense The Wicked + The Divine is a sort of contemporary equivalent of The Golden Bough, a very influential if unscientific text published in 1890. It was written by a prominent culture studies academic named James Gordon Frazer endeavoured, and purported to provide a common etymology of European / Middle Eastern mythology.

The innovation of the story, as stated above, comes from mixing godhead with social media and the other technological indicia of contemporary times. A young person with devastating magical powers and a cult following is almost certainly going to become the ultimate influencer. The interconnectivity of modern telecommunications was something that was obviously not available to previous incarnations of the godlings. That concept was perhaps the most compelling aspect of the story.

Teen pregnancy and the right to be forgotten

The narrative character, Laura, was a fan girl who unexpectedly became the most powerful of all of the gods, the terrifying Persephone, also known as the Destroyer. In this volume she reveals she is pregnant. This understandably has an extremely sobering effect upon Persephone, and she tells two of the men who might be the father of her child, Baal and Baphomet.

Laura decides that she no longer wants to be a god, and apparently wills herself to be human. She has an abortion, something which is very painful and personal. It is handled very well here – the rawness of the decision is something the reader can feel. Even her enemies are sympathetic and leave her be.

But then, hiding in an underground lair, she finds she has a new power. Or is it an old power? What is going on here? God, not god, god. It is an unnecessary twist.

Otherwise:

1. The youngest character, Minerva, has evolved backwards from being a pre-teen who poignantly knows that she will die young, to somehow being a youthful clone or at the very least accomplice of Ananke. This is very confusing; and

2. Baal, a powerful alpha male, egotistical but fundamentally altruistic, is not actually a god of storms. Baal is actually a god of fire, not at all altruistic, and he kills a teenager every few months so as to prolong his life. “It… it’s not sadistic. I’m not cruel. The kids are drugged and…. fuck it. You don’t need to know the details.” This pointless twist appears to have been suddenly introduced for shock value.

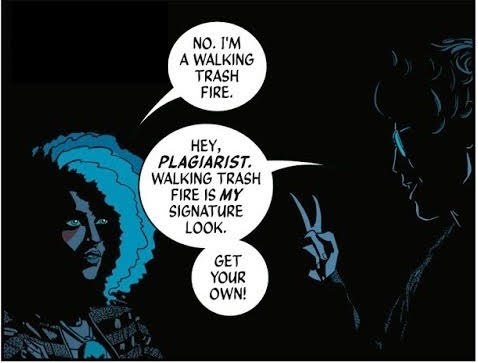

None of this is clever. It is like watching a gasping fish flip and twist about, trying to save itself.

We have previously written about earlier volumes, in 2015 and with high levels of praise. Our enthusiasm for this title has significantly waned as the story has progressed. Nonetheless we will be following it to its imminent end.