Writer: Saif A. Ahmed

Artist: Fabiana Mascolo

Scout Comics, November 2021

A GLIMPSE OF A FAMILY’S LIFE emerging from the ruin of Iraq is a welcome addition to our stories. Many voices are beginning to appear lately from past and present war zones.

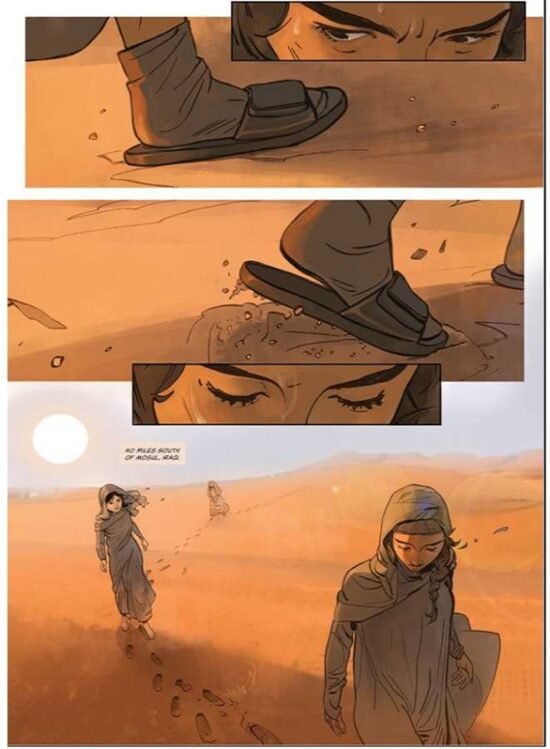

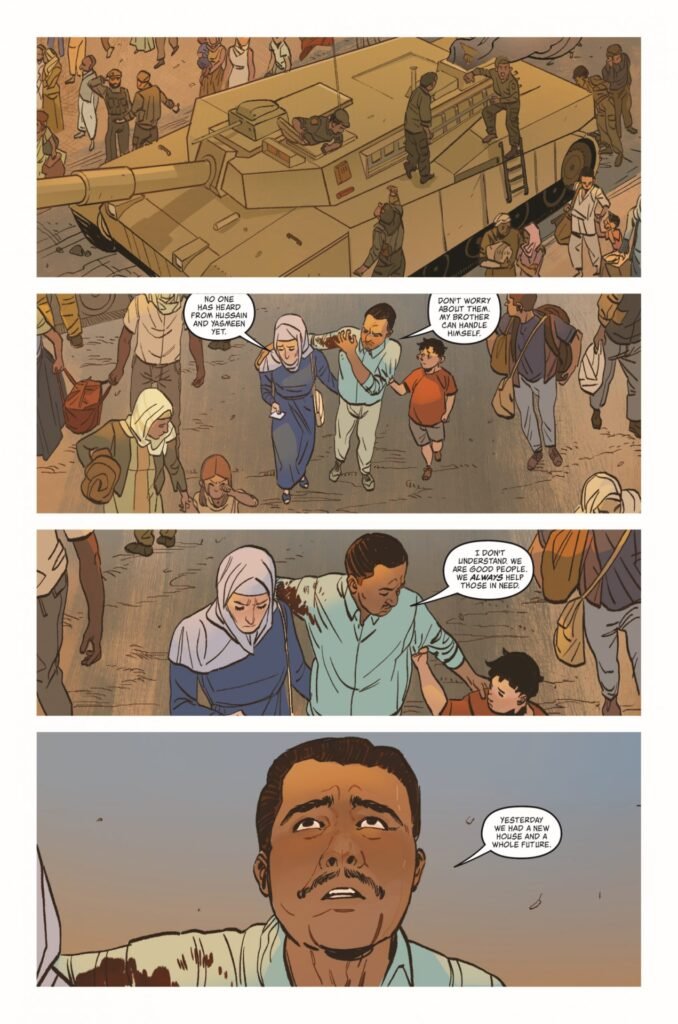

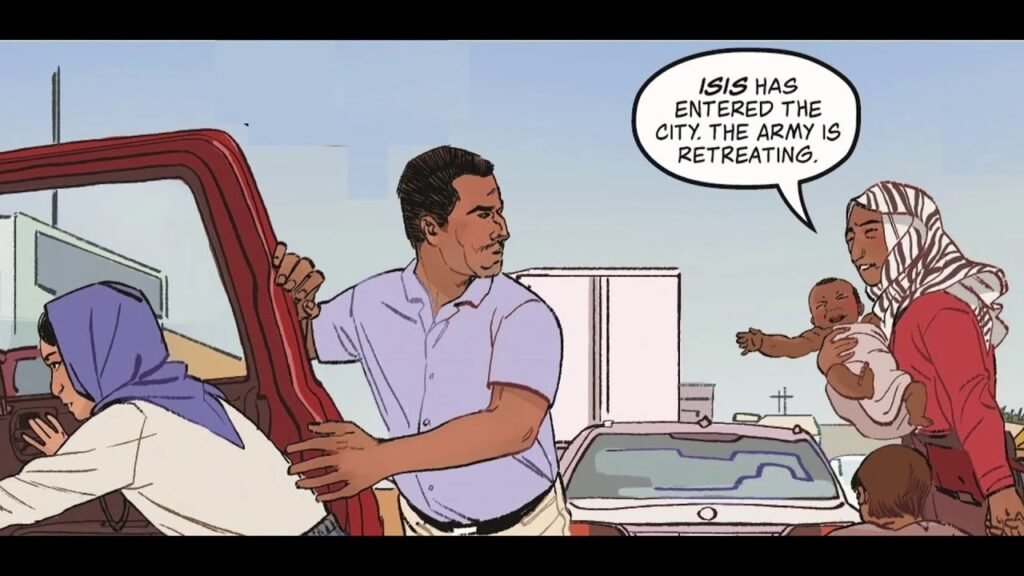

YASMEEN appeared in my hand in six issues from 2020, and I was attracted by its personal chronicle, in this case following an adolescent girl abducted into sexual slavery when the metropolis of Mosul in northern Iraq where she lived was overrun in 2014 by troops of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS). It’s a gruesome story.

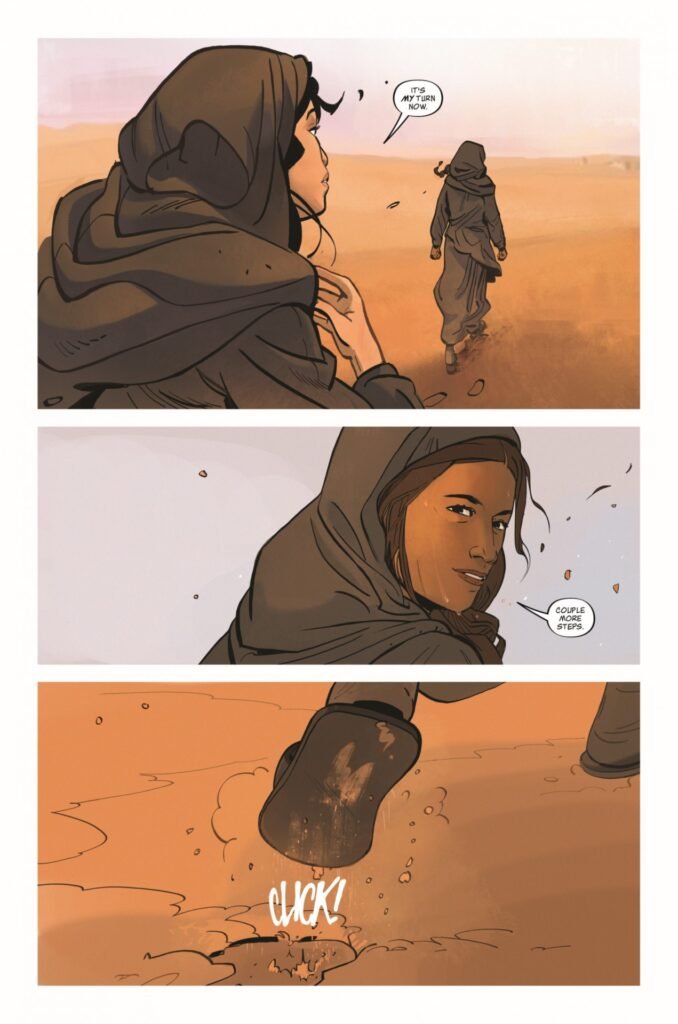

Writer Saif A. Ahmed skirts the personal horror of his topic to make it appealing enough to listen. Art by Fabiana Mascolo is nicely done, crisp and complete, always embedding the actors on the stage in real backgrounds.

The characteristics of the writing and art together, subdued, crisp, sketched in detail while staying within the lines, made it quickly feel to me like a graphic screenplay ready to mimeograph and shop around. I began to suspect the writer was writing because he wants to be a storyteller with movie options, rather than starting with a story to tell. The art falls in line and began to feel flat.

Emotional contact with Yasmeen is continually jarred by abrupt scene changes every couple pages, shifting both place and time at once, apparently spliced after the fact for dramatic effect when all the pages were strewn around on the author’s living room floor; not a fantastic notion after finding a page tacked at the end of Issue 3 that was left out in error from the previous issue. Who could notice? For all its crisp technique, the rhythm feels like an iron-wheeled carriage rumbling on cobblestones.

Yasmeen’s story itself feels cobbled together from television dramas and news headlines into a good guy bad guy action thriller, adding standard props from Islamic tradition: most prominently the principle of alms, and mortal family feuds over female honor. There is a reference to Wahhabism, a radical version of Islam, or something sprung from Islam, espoused by the contingents of ISIS and housed as the state religion of Saudi Arabia. Yasmeen herself is a standard adolescent heroine going from spoiled brat to the bottom of despair to revolt and triumph.

US soldiers departed Iraqi cities in 2009, including “troubled Mosul” near the borders of Iran, Turkey, and Syria, and the frontier of Kurdish territories long exposed to terror from all sides. Mosul as the second-largest city in Iraq after Baghdad was targeted in the original shock-and-awe campaign launched by the USA and its partners in 2003. The Iraqi government left in charge later as a beacon of democracy promoted sectarianism and bred predatory soldiers. These are the good guys in the story waiting to shelter Yasmeen after her trial escaping through the desert.

The abuses of the post-war Iraqi army in Mosul, coupled with hatred for Americans and those that supported them never appear in this story. Everyone is just happily going along until ISIS arrives. Dad just bought a big new house. The bubble around Yasmeen and her family can only have occurred if dad was a collaborator with Western forces. That explains how he gets to America so quickly, though it does not explain why he would leave his daughter behind in this place to tag along later. I prefer to think the writer as in many other instances simply had a lapse of reason that failed to register while thumping along.

War and terror in the region erupted in a bright line in 1979 as a clear marker in history, according to a brilliant account assembled by Kim Ghattas in Black Wave: Saudi Arabia, Iran, and the Forty-Year Rivalry that Unraveled Culture, Religion, and Collective Memory in the Middle East (2020). As in other places, the US response to the radical revolution in Iran in 1979 that overthrew the Anglo-American-backed Shah, involved subterfuge and infusion of mind-boggling amounts of heavy weaponry to opposing factions: in this case supplying both Iraq and Iran with weapons, while egging the two countries into war with each other.

This weird ploy, exposed in the famous Iran/Contra scandal in the 1980s, created the first American-backed war in the region. The radical government in Iran took root as defender of the homeland. Meanwhile, a similar extreme model of Islam fused nearby in Pakistan as the US war machine, ever busy, propped up a tyrant there in order to secure a base for its secret war against the Soviets in Afghanistan. Again, mind-boggling amounts of weaponry were transferred to extremist factions. Cadres of well-funded, well-armed radicals spread across borders.

The secular government in Afghanistan had liberated women as the Soviet Union had done among its constituent peoples over the past decades. Secular Iraq under Saddam Hussein had also liberated women. Fundamentalist Islamic sects as well as Saudi Arabia were not happy about it. US funds and arms set up well-fed factions as with Osama bin Laden, and larger amounts of Saudi money followed up, pouring out across the region to spread repressive sectarian views through community education and pressure groups.

A news photo recently shows the US president bumping rings in a fist-bump with the current Saudi leader, harmonizing, briefly exposing the current of the black wave. Currents themselves are usually invisible, one sees only the content skimming along.

Disunion and devastation surrounded Yasmeen’s young life, yet neither her nor anyone around her seems to notice. In her book on the black wave devouring the Middle East, Kim Ghattas leaves America in the background to shine light on the up-close antagonisms tearing countries and peoples apart, genuinely local and genuinely intense, without America and other Western powers needing to stir the pot very much but with their caches of weapons that never run dry. I supposed the author of Yasmeen’s life might also have decided to avoid messy talk to keep the focus simple.

The effect here, though, is blurred. We return in the last issue to two girls walking in the desert, the girls from the first couple pages in Issue 1, apparently, where one girl steps on a landmine. I had to check to be sure that actually happened, yes, three girls then, two girls now. At this moment the bad guys are shooting at them; only Yasmeen makes it through. By this point, with all the flashbacks and flash forwards to different places, the emotional drama with Yasmeen at this epiphanic juncture failed to register. Why did we see a flash of this in the beginning when it made no sense for six issues?

What did register and made me wince at this point was the similarity to an eyewitness account from the World Tribunal on Iraq (2008), describing how American forces subdued insurgents in an Iraqi city by surrounding the city entirely and shooting anything that moved inside and outside the perimeter before squads penetrated. Loss of innocent life was massive and indiscriminate. The 2019 US-backed invasion of Mosul was similarly blamed for “callous use of artillery and air power that killed too many civilians.”

A research mission to Iraq before the American-led invasion in 2003, sponsored by the Center for Economic and Social Rights, and Physicians for Social Responsibility, reported the devastating results of 12 years of economic sanctions—a punishing policy now a US favorite that one American leader has called the killer drone of the future—or as it happens, already killing now. Deprived of many necessities since the first American invasion in 1991, the people of Iraq lacked resilience to meet new challenges.

The research report from Iraq, issued as shock and awe was already poised to strike, predicted: “In event of crisis, 30 percent of children under 5 [approximately one million children] would be at risk of death from malnutrition.”

Did we ever hear this in our news? One million children dead? Ever? Probably worse after things got way out of hand; the catastrophe turned out more devastating than the Mongol invasion. These are the years when Yasmeen was born.

Mosul was a flashpoint throughout the American occupation, with some notable grisly acts by the population that led to major offensives against the city. By 2008, a year before the exit of US forces, violence in northern Iraqi cities had not abated. Depleted uranium from massive shelling, especially around Mosul, was certainly the cause of breast cancer incidence in the area quickly doubling.

I wrestled with myself over these images of reality on the ground in Iraq, trying to excuse the author for the people in his play missing these messy truths of misery, death, and destruction all around them, until I came on a letter by Daniel Bessner just now as I reach the end, responding to a reader in the current issue of Harper’s Magazine (Sep 2022), saying what I need to say:

“He warns about the ‘brutality of relevant alternatives’ to US empire. I would only ask him what people in Fallujah, Kandahar, or Sanaa might say about the benevolence of the ‘US-led world’ he cherishes.”

*

NB. Other sources provide key information: John Robertson (2015) on Iraq, Tim Weiner (2007) on the CIA, Stephen Glain (2004) on the Arab world. The letter by Daniel Bessner in Harper’s defended his proposal for greater restraint in US foreign policy in an essay “Empire Burlesque” that appeared in July.