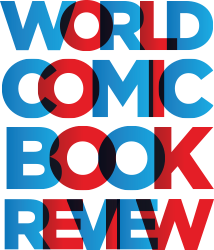

From 1981 to 1983, veteran comic book writer Roy Thomas was the driving force behind a title called All-Star Squadron, set in 1942. Mr Thomas grew up in the 1940s and used now out-of-date idioms so as to accentuate the time period. The characters’ colloquial speech, hairstyles, dress, and attitudes towards both women and minorities all keenly underscore that fact that the stories all take place in World War Two. These stories have not dated because, curiously, they were already dated in 1981: the various indicia of 1942 made the title stand out as a period peace.

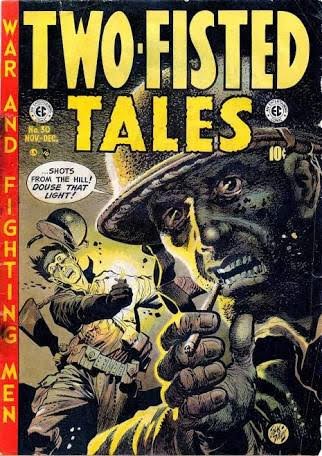

Hawkman, Liberty Belle, and Johnny Quick all “keep ‘em flying, hear?” in various issues of All-Star Squadron, 1981.

All-Star Sales Figures

American comic books were launched as an industry immediately prior to World War 2. The American superhero genre firmly has its roots in World War 2. Some of the characters predate the war (notably, Superman, who first appeared in 1938). But the vast majority of superhero publications and their characters appeared after hostilities commenced. These tales of costumes heroes captivated audiences in the 1940s. Sales of superhero comics during this period were at their zenith during this period. According to The History Rat blog.

“When the war began, 15 million comic books were being published a month. Two and a half years later, 25 million copies were sold a month. Superman and Captain America each sold over 1 million editions a month. And the largest single customer in the period was the United States Army…. The most surprising influence the comics had was on those who actually participated in combat. The books were seen as something to take their mind off what was to come and what had taken place. They were cheap, easy to carry, and the comic itself didn’t require a college education to read. It was part entertainment, part instructional manual, and part psychologist for the soldier.”

Unsurprisingly, characters appearing in these stories had a firmly patriotic tone. The stories in their own way assisted the war effort.

Bellus Fugit

In 1981, when Mr Thomas first began writing All-Star Squadron, World War 2 had ended only 36 years before. Those who directly participated in hostilities and survived, as grandfathers and grandmothers to Mr Thomas’ readership, had their own stories to bolster those of All-Star Squadron.

But it has now been 73 years and the war has almost passed out of living memory. Other world events and the passing of the participants have rendered World War Two yet another war in history, notwithstanding the genesis of comics during that period.

One of these characters have been constantly in publication since then, and the characters’ war origins have been preserved: Marvel Comics’ superhero Captain America. The character’s origin is too interwoven with World War 2 to be erased, and that genesis has been repeatedly reinforced over the years:

But no other significant character’s World War 2 origin has been maintained. DC Comics in particular had a vast array of characters who participated in World War 2. DC Comics decisively recalibrated this “Earth-2” set of characters in 2011, whereby instead of having their origins and participating in World War 2 albeit on an other dimensional Earth, the characters instead have very contemporary origins. Mr Thomas’ meticulous work on All-Star Squadron and related titles, his jigsawing of his own stories into the plots and foibles of the publications of the 1940s, has been gradually unravelled. We are left with great period stories standing outside of the continuity ecosystem which sustains American superhero comics.

World War 2 stories are obviously not restricted to the superhero genre. Many other titles based in World War 2 stories consist of the stories of soldiers and victims of war – but, interestingly, none of these title had their genesis during World War 2. Paramount amongst these types of titles are:

1. Our Army at War / Sgt Rock (DC Comics, 1952-1977)

2. Weird War Tales (DC Comics, 1971-1983)

3. Sgt Fury and His Howling Commandos (Marvel Comics, 1963-1981)

4. The Unknown Soldier (DC Comics, 1966-1982)

5. War is Hell (Marvel Comics, 1973-1975)

6. G.I Combat (DC Comics, 1952-1987)

7. Star-Spangled War Stories (DC Comics, 1952-1977)

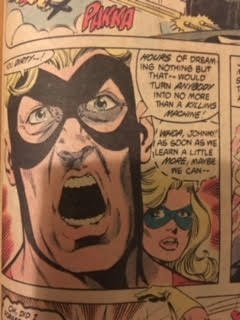

8. Two-Fisted Tales (EC Comics, 1950-1955)

9. Frontline Combat (EC Comics, 1951-1954)

10. Blazing Combat (Warren Publishing, 1965-1966)

11. Maus (Pantheon Books, 1980-1991)

12. The Rocketeer (Pacific Comics, 1982)

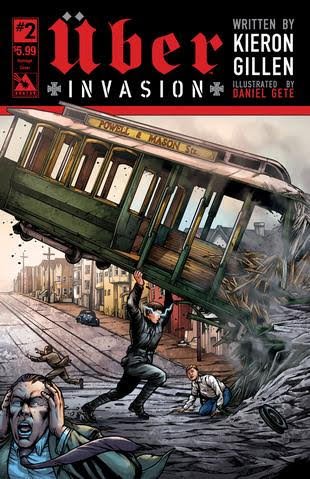

In more recent times, The Light Brigade (which, amusingly, features an American soldier with a superhero comic collection which he carts across Europe: one of the issues, to his horror, is used as toilet paper by a comrade) and Kieron Gillen’s Uber have revisited the time period. (We have also reviewed the wonderful story of the German invasion of France, Suite Française: Storm in June.) But these are the exceptions to a drought.

The gradual passage of time diminishing and fading the stories of hardship and comradeship is hardly particular to World War 2. The popular English idiom, “It does not matter what you do, if you were at Waterloo” excused the behaviour of veterans upon the conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars, with the defeat of the French at the Battle of Waterloo. That saying has been consigned to history and is virtually unknown now. As history marches on, will the stories of World War 2 will blur and be lost, replaced by stories and legends of more recent times?

We see that very clearly with World War 2 titles which have been reworked for a contemporary audience: DC Comics’ The Losers has no recognisable connection to the original World War 2 series. Instead it is a story invoking the CIA, war in Afghanistan, and conflict driven by the “guns, oil and drugs” of millenarial ambitions which are not territorial. The re-tooled version of DC Comics’ title The Haunted Tank has a closer resemblance to the original World War 2 story, but nonetheless involves an American tank crew in Iraq.

War plane Art as Muse

One other World War 2 title has been very successful, and unexpectedly so. DC’s Bombshells features various female characters from DC Comics’ panoply of characters, reimagined as superheroes in the 1940s. The comics were inspired by popular collectable statue art featuring the characters. There is a strong feminist theme to the stories, a reminder that while men were off fighting in the war, American women in particular were in factories and otherwise running many civilian aspects of national life. We have favourably reviewed this title before in 2015. We noted in that review the sexualised covers were counterbalanced by the feminist tones of the book. The title concluded in 2017. A subsequent title, Bombshells United, ran for seventeen issues and was cancelled earlier this year. (An earlier version of this article omitted DC’s Bombshells: an oversight.)

Above: World War 2 war plane art. Below: Harley Quinn from DC’s Bombshells

Did World War 2 sell the title, or were sales achieved through the clever melange of feminist perspectives and sexy war plane art? Perhaps instead the latter is an important subset of the former.

Revelations of The Red Horseman

World War 2 is called “the good war” (with increasing controversy) because of the stark division between the liberating Allies and the depravities of the Axis powers, including notably the Holocaust. And that horrific event in particular is a key distinguishing factor between World War 2 and other wars. The Great War (World War 1) has enormous loss of life, but that loss was promoted by all sides, and the public in the United Kingdom and especially France was derisory of their leadership. World War 2 was instead characterised by liberators seeking to repel Japanese and German invaders – a much more clear cut case of good v. evil – and one accentuated by events such as Auschwitz and the Rape of Nanking, both of which became public knowledge after the conclusion of the war.

But the concept of the “good war” is one which has been subject to critical scrutiny in recent years. Mr Thomas was, perhaps, always conscious of it even within the stereotypical “good v. evil” paradigm of superhero comics. In what was perhaps the best of all of his writing, All-Star Squadron #18 and #19, the members of the Justice Society have been captured by the villainous Brain Wave, and are being subjected to horrible dreams of war time:

As the Justice Society members are trained to brutally kill, Johnny Quick is repulsed by their bloodthirsty brainwashing. But killing is what soldiers do, irrespective of whether they are in the good war or not. Indeed, in All-Star Squadron #3, the Justice Society of America is disbanded so that each of the heroes can join the US Army (save for Johnny Thunder, who joins the navy). The story in All-Star Squadron #19-20 culminates in Green Lantern using his enormously powerful magic ring to destroy a dream version of Tokyo, in a clear parallel to the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki (see the image at the beginning of this review). As a consequence, Green Lantern is reduced to tears, a broken man.

The conclusion of “the good war” involved the deaths of hundreds of thousands of civilians. In the case of Japan, this involved not just the two notorious atomic bombings and their questionable morality, but also the repeated napalming of Tokyo, masterminded by the ruthless US General Curtis Le May. Tens of thousands of non-combatants ran from their wooden and bamboo homes, seeking refuge from the fire within Tokyo’s waterways. These people – the elderly, women and children – were boiled alive. Mr Thomas was a young teenager during the war, and would have spoken to American veterans. Some of them must have been reduced to tears in telling their stories. He knew victory had a ghastly price.

Once, we might have given forlorn looks back to a time when it was clear who was good and who was bad. It was the ideal ecosystem for the superhero battle of good guys pitted against bad guys, and indeed gave birth to the genre. Perhaps it is not so much the passage of time that removes World War 2 from the frame of reference of pop comic book culture, but the realisation that the Allies in “the good war” defeated profound evil, but otherwise, was not really so good after all.