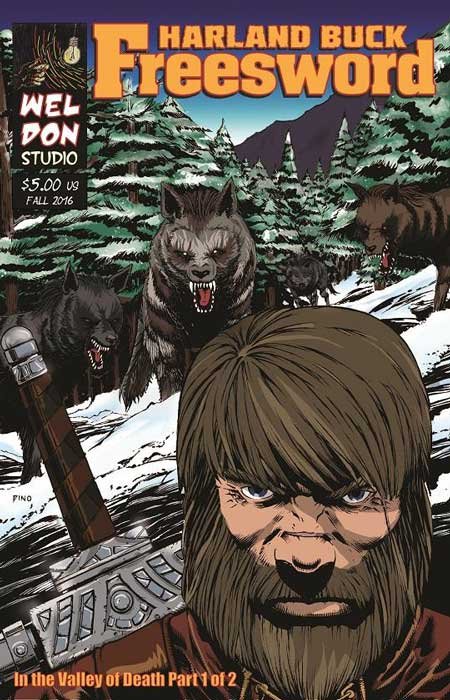

Harland Buck: Freesword #1

Weldon Studio

Writer: Scott Weldon

After the fall of the Roman Empire, kingdoms rose and fell into obscurity. Waves of armies and their retinues – some nomadic and some seeking better prospects – settled into the niches left by the Romans. One of these, the Kingdom of the Rock, near Clydebank immediately west of modern day Glasgow, though once extensive and powerful is barely remembered today even by locals, and allusions to its existence can only be gleaned by careful consideration of contemporary records.

The writer of “Harlan Buck, Freesword”, Scott Weldon, creates for his readership the entirely believable world of the Kingdom of Alo’vyn and its colonies in Emeraein, both lands with vaguely Celtic names but in unspecified places which could easily have existed but been lost in the mists of time and the shifting of civilisations. The protagonist, Harland Buck, is a “freesword” – an independent mercenary. Buck’s face is scarred and he is a fearsome melee fighter. His dour exterior hides empathy: in circumstance where he could save himself from the elements, Buck is by his actions quietly determined to save the life of a bleeding and badly injured young soldier, a Realmguard who has taken to the king’s service in exchange for land to farm.

The Realmguard, named Kendell, has fallen from a wagon, and Buck tries to save him falling to his death by leaping after him. The wagon is part of a caravan carrying gold in the dead of winter. The wagon wheel slides off the narrow and icy path, and so both men left at the base of a steep incline and in a forested valley. Buck knows that their prospects of survival are meagre, especially if a storm strikes the valley, but silently resolves to help the wounded young man return to his wife and daughter.

The Realmguard, named Kendell, has fallen from a wagon, and Buck tries to save him falling to his death by leaping after him. The wagon is part of a caravan carrying gold in the dead of winter. The wagon wheel slides off the narrow and icy path, and so both men left at the base of a steep incline and in a forested valley. Buck knows that their prospects of survival are meagre, especially if a storm strikes the valley, but silently resolves to help the wounded young man return to his wife and daughter.

But, as Buck notes to himself, “Valor can only carry a man so far.” The two face off against a pack of wolf-like creatures which Buck calls “canix”. As the first issue ends, barely having fought off an attack by the canix, things look grim. The repeated reference by Kendell to the names of his wife and daughter, giving them identity and thereby emotional connection to the reader, indicates that the man might die during the quest to safety, the express desire to return to wife and child foiled by the wagon’s slippery wheel.

Mr Weldon assists the reader to understand some of the context with an introductory précis which he calls a “cyclopedia”. In a novel with its eternity of pages this would be a little lazy: but within the confines of a twenty-four page serialised story this is instead very helpful to get a leg-up into the fantasy context.

It is tempting to see the wagon’s wheel as a metaphor for the wheel of fate. But instead the story is unladen by hidden symbolism or moral message. It is a simple trek through ice and danger. The only mystery is that Buck carries a sword which, in inner monologue, he calls a “Morat Blade” and which he says to himself that he earned the right to wield. It is a visually striking-enough weapon to attract the eye of the Realmguard, and Buck apparently has a history of not using it even when surrounded by multiple foes. This obviously prompts the question: what is it? Mr Weldon would have better positioned the mystery by removing the descriptive inner monologue and hinting at the weapon’s importance in other ways. Inner monologue, popularised in American comics by thought balloons and then rendered almost mandatory by Frank Miller’s “The Dark Knight Returns” (1986-7) removes the benefit of slow construction through action and dialogue, and is a trap for the experienced and inexperienced alike.

But this is a small criticism. This is an entertaining story, an adventure which is both accessible and engaging.