Harley Quinn and the Suicide Squad #1 April Fool’s Day Special (review)

(DC Comics, May 2016)

Writer: Rob Williams

The publication, “Harley Quinn and the Suicide Squad #1 April Fool’s Day Special” is a story which skims thematic tones and mise-en-scenes like a hockey puck on ice. American comic book publisher DC Comics has issued this, no doubt, to tie in with the forthcoming motion picture, “Suicide Squad”.

In trailers for the film, Australian actress Margot Robbie steals the show in her role as the psychotic character Harley Quinn. Harley Quinn, an adversary.of DC Comics iconic hero Batman, is a brawler with no super powers, and as such the character property’s status as a fan favourite is a little unique. Harley Quinn has as a foundation an almost Japanese combination of madness, violence, and raw coquettishness, triggered and perpetuated by an “amae” relationship with one of the most vile and murderous of all comic book villains, The Joker (“Amae” is a Japanese word meaning a subconscious sense of reliance, a desire to be loved, and submissive desire).

This issue, as the title suggests, focusses on Harley Quinn, with other Japanese manga elements. For most of this issue the story is light-hearted and effervescent. The beginning of the story involves Harley Quinn in a state of “hikikomori”, hiding from society in a room eating junk food, with poor hygiene, and suffering delusions.

After being anonymously delivered a folder relating to psychiatric help to supervillains, Harley Quinn essentially taking a joy ride on the winged back of an ancillary Batman character called Man-Bat (as the name suggests, a giant humanoid bat). Harley Quinn madly and very visibly rides Man-Bat like a bronco through and around the high rise corridors of Batman’s home town, Gotham City. The character outlandishly draws attention to herself.

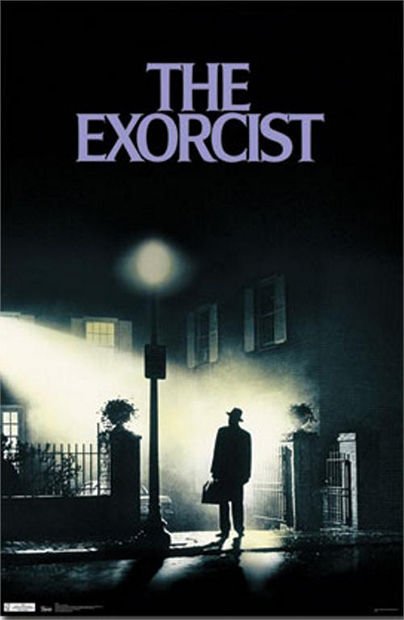

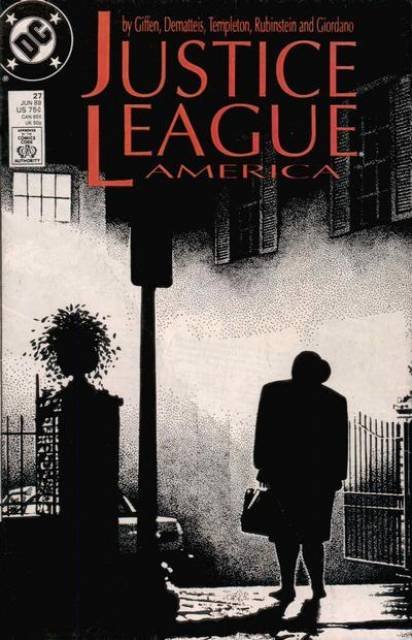

The folder is apparently delivered by the Machiavellian figure Amanda Waller, a looming character in DC Comics’ various continuities (and we will talk more about this very intriguing character at some stage in the near future): in silhouette, Amanda Waller’s appearance resembles the promotional poster for the horror movie “The Exorcist” (1973), and this is not the first time Amanda Waller has been depicted as such. Below is an image of the panel, the poster for “The Exorcist”, and also the cover for ‘Justice League America” #27 (volume 1) (July 1989) depicting Amanda Waller:

This panel is important. Amanda Waller rarely brings relief from demons, and as this story unfolds it becomes apparent that her role is precisely the opposite.

The title character then suffers a head injury. As a consequence the art cleverly shifts from artist Jim Lee’s photorealistic drawings to artist “Cheeks” Galloway’s cartoonish drawings The sharp change of gear in the artistic style literally illustrates the light-headedness or even childhood euphoria of Harley Quinn’s injury. It is a clever plot shift by writer Rob Williams. Similarly the concepts and plot shift from crazed and outlandish to being very silly and light-hearted. Harley Quinn takes on the bubbly and misguidedly altruistic role of a psychiatrist to various villains sitting on the traditional couch, ranging from the chatty and surprisingly likeable Killer-Moth to a creepily silently woman possessed by the alien conqueror Starro. These exchanges are fluffy and amusing, fit for a Saturday morning children’s animation.

Harley Quinn cannot control herself for long though and her cartoon doppelganger, together with another female Batman adversary called Poison Ivy, soon decide to take advantage of the information Harley Quinn has obtained as a psychiatrist to rob her patients. The compulsion to engage in crime is overwhelming but amusingly executed by Mr Williams.

This then leads to a confrontation with superheroes comprising the team called the Justice League, who are responding to what they think is a cabal of supervillains. The art at this point abruptly shifts back to being photorealistic. Harley Quinn is secured in a straight jacket created by the energy plasma of Green Lantern’s alien ring, and is to be hauled away to a cell.

The Justice League are posturing, and almost sickeningly righteous in their easy victory. The heroes are depicted in a way which causes even the reader to mildly despise each of them. This is an interesting perspective of the ordinarily beloved characters. It is rare indeed for DC Comics to allow its major character properties to be portrayed in a diminutive way.

Harley Quinn, filled with revulsion, manages to break Batman’s nose with a vicious headbutt. Surrounded by the self-assured superheroes with their godlike powers, this is a human demonstration of contempt against the omnipotent worthy of Ahab, Herman Melville’s antagonist in “Moby Dick” (1851). Incidentally the character demonstrates that even bound, even surrounded by this collection of superhumans, she is not to be trifled with.

And then we are suddenly witness to Harley Quinn, her eyelids held open by surgical claws, being subjected to a type of image-led brainwashing by spymaster Amanda Waller. This is the nasty April Fool’s Day joke promised in the title of the issue, delivered upon both the character and the reader. The candy floss of the intermission is either a delusion from the head injury, or the result of Amanda Waller’s tortuous priming of Harley Quinn for combat with superheroes. The bubbly interlude juxtaposes against the sight of the supervillain being psychologically damaged. The other members of the Suicide Squad are geared up and ready to go “cape hunting” (fighting superheroes), and Amanda Waller explains to them that she has put Harley Quinn through brainwashing to ensure she is sufficiently brutal enough for the next mission.

As she sits manacled to a chair, Harley Quinn tearfully asks Amanda Waller whether the psychiatric sessions with the other supervillains, the confrontation with the Justice League, was real. Amanda Waller replies, “Does it really matter?” And Harley Quinn replies, “No.” And Harley Quinn mutters a response, “I just wanted to help.” The instance of altruism, of assisting the mentally ill, might be a dream, and in any event does not count. It is a crushed hidden hope of rehabilitation.

Where, amidst the psychosis, the concussion, the brainwashing, do each of the realities begin and end? There is something of the essence of the misogynistic and sadistic movie “Suckerpunch” (2011) in this story, with layers of delusion and warped perspectives shared with the audience. But this story lacks the greasy misogynistic elements of “Suckerpunch”, and is in its own way much more brutal.

“What if I could offer you a country… a world… without the super-folk? Would you like to be involved in that?” Amanda Waller asks, her face cast in shadow. “Very much,” replies Harley Quinn, her eyelids pinned back, her face covered in sweat, taunted by delusional, serpentine images of the Joker.

It is a jarring conclusion to the issue. “Harley Quinn”, both the concept and the character, is saccharine sweet and “otaku” (isolated obsession with a collectable mania) but only to a point. This is a surprisingly sinister, engaging portmanteau: essentially four stories interwoven, to bleak effect.